This article is in essence a chapter of a book in progress on the familial relationships between the Schindler and Weston families and their bohemian social circles between 1920 through 1938. For now I plan to end the book in 1938 when Weston married Charis Wilson and built his home in Carmel Highlands and the Schindlers divorced and began living separate lives under the same roof in their iconic RMS-designed Kings Road House. My working title for the book is The Schindlers and the Westons: An Avant-Garde Friendship, 1920-1938. Their fascinatingly interwoven lives and relationships remained avant-garde and bohemian to the end. As always, I welcome your feedback on any of my pieces.

This chapter of the Schindler-Weston connections centers around the intertwined relationships of Pauline and Rudolph Michael Schindler, Edward Weston, Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Cole Weston, Nellie Cornish, Maurice Browne, Ellen Van Volkenburg, Ellen Janson, John Steinbeck, Ed Ricketts, Joseph Campbell, Henry Cowell, Richard Buhlig, and their circles. As the introductory image to this article I have chosen the below 1920 tongue-in-cheek photograph taken at the time of Edward Weston's first meeting with artist Roi Partridge and his wife Imogen Cunningham, an early Seattle friend of Cornish, whose importance to the story will emerge later. This history-packed image was taken on the occasion of Edward Weston's visit to San Francisco to see off his Dutch emigre photographer friend Johan Hagemeyer who would soon leave for an extended trip to Europe to avoid being arrested for his outspoken radical views. (Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles, by Beth Gates Warren, Getty Publications, 2011, p. 187).

"Anne of the Crooked Halo," June 1920, photographer unknown. From left: Roi Partridge, Imogen Cunningham, Anne Brigman (standing), Johan Hagemeyer, Edward Weston, unknown man, (front) Roger Sturtevant and Dorothea Lange. Woman behind them unknown. From A Poetic Vision: The Photographs of Anne Brigman by Susan Ehrens, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1995, p. 83.

The image's centerpiece, Anne Brigman was looked up to at the time as being the only photographer on the West Coast accepted into Alfred Stieglitz's Photo-Secession Movement and featured in his influential Camera Work magazine. Roi Partridge was a noted etcher and wife Imogen Cunningham an emerging photographer of note who would later be part of Group f/64 with Ansel Adams, Weston, Willard Van Dyke, Sonya Noskowiak, et al. Their son Rondal Partridge later became a well-regarded art and architectural photographer as did Roger Sturtevant. Dorothea Lange would also gain fame as a chronicler of the Great Depression. Pauline Schindler often featured the work of Sturtevant, Hagemeyer, and Weston on the cover of The Carmelite and reviewed exhibitions of their work along with that of Cunningham and Partridge during her 1928-29 reign as publisher and editor-in-chief. Pauline also published a portfolio of Lange's photos in an article on migrant worker housing in the December 1935 issue of Architect & Engineer which she guest-edited. Lange's 1935 portrait of Pauline (see below) was taken around the time John Cage broke off his brief affair with her to marry erstwhile Edward Weston lover Xenia Kashevaroff.

Pauline and R. M. Schindler's introduction to the Weston family came about in 1921 when Pauline began teaching Weston's sons Chandler and Brett at the Walt Whitman School in Boyle Heights, shortly after her and her architect husband's arrival in Los Angeles. (See my The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School). At about the same time, her theater idols from her Chicago days, Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg, established a drama department at the Cornish School in Seattle. (See later below). Browne and Van Volkenburg were the founders of the Chicago Little Theater in 1912, a critically acclaimed experimental troupe inspired by the Irish Players at Dublin's Abbey Theatre, and early pioneers of the Little Theatre Movement. (For more on Browne and Van Volkenburg see my Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism).

While Pauline was teaching music and English at Jane Addams' Hull-House in 1916-17 upon her graduation from Smith College, she undoubtedly viewed the performances of the Hull-House Players under the direction of Laura Dainty Pelham whom Browne credited as being the true founder of the Little Theatre Movement in America. (Too Late to Lament by Maurice Browne, Gollancz, London, 1955, p. 128). She also likely subscribed to The Little Review (see below) about the same time as Weston and Margrethe Mather and more than likely attended the Browne-Van Volkenburg productions and Browne's friend John Cowper Powys' lectures at the Chicago Little Theatre in the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue. (For much on Weston's introduction to Mather's The Little Review crowd see Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, Getty Publications, 2011, pp. 99-102).

The Little Review, March 1915. (Note articles on 1925 Kings Road lecturer and life-long friend of Pauline, "Maurice Browne and the Little Theatre' by close friend John Cowper Powys and "My Friend, the Incurable" by frequent contributor Alexander S. Kaun, later Kings Road tenant, Schindler client and portrait sitter for Weston compatriot Johan Hagemeyer. For much more on Browne, Kaun, Weston and the Schindlers see PGS). (For much more on Powys, see my The Schindlers and Westons and the Walt Whitman School).

Browne and Van Volkenberg also collaborated with Pauline's mentor, employer, and Hull-House and Women's International League for Peace and Freedom founder Jane Addams, to produce a national tour of Euripides' "peace play" The Trojan Women during her time at Hull-House. One of the performances was at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Coincidentally, R. M. Schindler attended the exposition to view the architecture a few months after the Browne-VanVolkenburg performance. (See my Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence for more details).

Browne and Van Volkenberg were also involved with oil heiress, radical activist and later Schindler client Aline Barnsdall as early as 1912. Eager to start her own theater company in Chicago and produce her own plays, Barnsdall offered to build Browne and Van Volkenburg a larger, more modern theater than their 90-seat venue in the Fine Arts Building. She commissioned Norman Bel Geddes and Frank Lloyd Wright to design preliminary plans in 1915. Aline put the plans on hold as she moved to California the following year and opened a theater in rented space in Los Angeles. (For much more on this see my Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole and Their Dramatic Circles).

At around the same time Barnsdall commissioned Wright to begin design on her personal residence, Hollyhock House, which would eventually be built on Hollywood's Olive Hill, the 36-acre site Barnsdall purchased in 1919. Barnsdall's original vision for her Olive Hill compound was to also include a director's house and a theater but those plans never materialized. (From Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 21-23).

by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 21-23).

Construction finally began on the Barnsdall House in 1920 (see above). By then heavily involved with the supervision of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Wright directed Schindler, recently married to Pauline, to move from Taliesin and Oak Park to Los Angeles to oversee construction. (For much more on this see my "Tina Modotti, Lloyd Wright and Otto Bollman Connections, 1920" and "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association").

A couple months after the above article on the Oil Queen's home, Browne and Van Volkenburg were establishing the new theater department at the Cornish School.

At around the same time Barnsdall commissioned Wright to begin design on her personal residence, Hollyhock House, which would eventually be built on Hollywood's Olive Hill, the 36-acre site Barnsdall purchased in 1919. Barnsdall's original vision for her Olive Hill compound was to also include a director's house and a theater but those plans never materialized. (From Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill

"New Residence Tract Opening," Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1921, p. 4. Courtesy Architecture and Design Collection, University Art Museum, UC-Santa Barbara.

Construction finally began on the Barnsdall House in 1920 (see above). By then heavily involved with the supervision of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Wright directed Schindler, recently married to Pauline, to move from Taliesin and Oak Park to Los Angeles to oversee construction. (For much more on this see my "Tina Modotti, Lloyd Wright and Otto Bollman Connections, 1920" and "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association").

A couple months after the above article on the Oil Queen's home, Browne and Van Volkenburg were establishing the new theater department at the Cornish School.

Cornish School, Seattle, Washington, ca. 1921, designed by A. H. Albertson with Paul Richardson and Gerald C. Field. Photographer unknown.

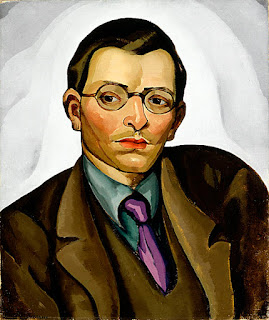

Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg, Seattle, 1921. Photo by McBride Studio. (Tingley, Donald F., "Ellen Van Volkenburg, Maurice Browne and the Chicago Little Theatre," Illinois State Historical Society Journal, Autumn, 1987, p. 133.

The Chicago Little Theatre had fallen on hard times during World War I and Browne and Van Volkenburg filed for bankruptcy in 1917. After vagabond stops in Washington (where they first met Nellie Cornish), Salt Lake City and New York they returned to Seattle in 1921 at Cornish's request. Cornish had just completed her new school building and offered the duo the directorship of her new drama school and theatre (see above and below). Browne had the highest regard for Cornish as he wrote in his autobiography,

"Nellie C. Cornish was the wittiest and untidiest woman in North America. Violent yapping preceded her entrance into a room; when she sat down a torrent of Pekinese cascaded over her. She had the soul of a master-pianist and hands unable to do her bidding on the keyboard, so she had gathered round her the best music-teachers whom she could find and opened a music school in Seattle. Students flocked. Often the most gifted had little money; she gave them scholarships. Sometimes they had none; she housed and fed them. Consistently she overpaid her teachers. Some students lacked rhythm, so she added a dance department. More students flocked. Some still lacked rhythm, so she tried to add a drama-department but could find no director who satisfied her needs. When the Chicago Little Theatre closed, she had paid Nellie Van and me the high compliment of offering us the position jointly." (Too Late to Lament by Maurice Browne, Gollancz, 1955, p. 263).

Announcement of the engagement of Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg as Directors of The School of the Theatre at The Cornish School. The Drama, Vol. II, No.s 11-12, August-September, 1921, p. 443.

Martha Graham and her dance students performing Heretic. Cornish School, summer 1930. Soichi Sunami photograph. Courtesy Cornish School Library.

Adolph Bolm, 1934. Edward Weston photograph. ©1981Center for Creative Photography. Arizona Board of Regents.

Cornish hired both famous and unknown artists for her faculty including abstract-expressionist painters Mark Tobey and Morris Graves and dancers Adolph Bolm, the Schindler's friend from their Chicago days, and Martha Graham (see above), a mutual Schindler-Weston circle friend who became an internationally renowned dancer and choreographer. (See my "Bertha Wardell Dances in Silence" for example.).

Cornish recruited Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg (the latter edited her 1964 autobiography Miss Aunt Nellie) to establish a drama school, and gave avant-garde composer John Cage his start. Weston's son Cole would enroll at the Cornish School in 1937, soon to be followed by Pauline's ex-lover John Cage and wife Xenia Kashevaroff (see below), erstwhile lover of Edward (and also likely Brett) Weston. Cage, who successfully sought out employment by Cornish as a music teacher, would remain at the school with Xenia throughout the 1938-39 academic years.

Xenia Kashevaroff, Carmel, 1931. Edward Weston photograph. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Edward Weston Collection, Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

While teaching at Cornish in 1921, a local music teacher brought Browne, also a noted poet whose work had just been published in William Stanley Braithwaite's prestigious Anthology of Magazine Verse for 1920, a sheaf of verses written by her niece, Ellen Margaret Janson. After weeks of reluctance to read the unsolicited poems, Browne relented and was pleasantly surprised. He wrote,

"Then to my wonderment I found that, though among them were exercises and immaturities, half-dozen held magic unequaled by the lyric verse of any American woman-writer known to me save Edna Millay. Nor were those half-dozen 'lucky flukes'; internal evidence showed that their author was a skilled and careful craftswoman, who knew precisely what she was doing. Like a pasteboard figure in an Oscar Wilde fairy tale falling in love with the ghost of a Babylonian princess I dashed in search of the music-teacher's niece. What could be more innocent than a love-affair with a poem?" (Browne, p. 276).

The forty-year old Browne immediately began an affair with the twenty-one year-old Janson and with his close friend from Chicago, Arthur Davison Ficke, began promoting her career as a poet in such publications as Contemporary Verse. (See below).

Excerpt from "Contributors," Contemporary Verse claiming the discovery of contributor Ellen Janson, Vol. XII, No. 5, November, 1921, p. 2.

Browne, Maurice, "Nightfall," Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, Vol. VI, No. 11, May 1915. Courtesy of the Poetry Foundation.

Janson, Ellen, Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, Vol. XXII, No. III, June 1923. From my collection.

Also likely with Browne's introduction, Janson was soon a contributor to his Chicago friend Harriet Monroe's Poetry: A Magazine of Verse in which his work first appeared in 1915 (see above). Besides Contemporary Verse and Poetry, Janson also soon began appearing in American Mercury, The Measure, North American Review and numerous other literary journals and was also anthologized by Braithwaite. Pauline likewise regularly featured Janson's poems in The Carmelite as well as her, Maurice and their love-child Praxy's ongoing activities even after their separation and divorce (see below for example).

Untitled poem by Ellen Janson Browne and untitled portrait [Christel Gang, 1925] by Edward Weston. The Carmelite, April 10, 1929, p. 1.

Pauline and Janson would also later collaborate as associate editors on Gavin Arthur's short-lived Dune Forum. (See my PGS and The Oceano Dunes and the Westons). RMS and Pauline also knew Ellen Janson from her early 1920s involvement with one of the members of Aline Barnsdall's experimental theater group. (Sheine, note 27, p. 283). Ironically, Janson and Pauline's estranged husband would eventually become lovers after which she would have him design and build her a house in 1949 (see below). It was there that Schindler would convalesce after his second heart attack shortly before his 1953 death. Gavin Arthur and Ellen Janson would end up marrying in 1965.

Ellen Janson on deck of her Schindler-designed house under construction, Hollywood, ca. 1949. Photgrpaher unknown. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

Mark Schindler (left), Pauline Schindler and Leah Lovell and likely her sons Brook and David and other children in their School in the Garden, Ivarene Avenue, Hollywood, ca. 1926. (McCoy, p. 39).

Around the time Browne and Van Volkenburg were establishing the Cornish drama school, Pauline met Leah Press Lovell and her sister Harriet Press Freeman. Leah was then directing Barnsdall’s progressive kindergarten at Hollyhock House commissioned for her daughter Betty and other selected children. (Architecture of the Sun by Thomas S. Hines, pp. 142, 156). Pauline and Leah, wife of Weston family doctor and later Schindler and Richard Neutra architectural patron Philip Lovell, later moved their school to the garden of the Lovell house on Ivarene Avenue in the Hollywood Hills and later to the Neutra-designed Lovell Health House in Los Feliz near Griffith Park (see above and PGS). Through Pauline’s friendship with Leah and Harriet, Schindler would become architect to the Lovells and later the Freemans.

Browne had a falling out with Cornish after only one season. He and 'Nellie Van' moved on to San Francisco in 1922 where they became involved with Charles Erskine Scott Wood and Sara Bard Field in the planning of another Little Theatre and drama school to be established under their directorship. When she took over as publisher and editor of The Carmelite in 1928, Pauline would enlist Wood and Field as contributing editors along with their mutual friends Lincoln Steffens and his wife Ella Winter. (See below for example).

Kuster and his second wife Edith had earlier been involved with the renowned Ruth St. Denis Dance Company and after she teamed up with Ted Shawn, Kuster helped them form the Denishawn Dance Center in Los Angeles. The above photograph expresses her appreciation for his work and dedication to the theater arts. St. Denis shrewdly incorporated her patron's wife Edith in one of her marketing brochures (see below) touting her as "One of the most charming young society matrons of Los Angeles, who has given great pleasure at many benefits and charity performances with her Denishawn dances." ("Denishawn: A University of the dance. World famous in its third season," p. 9, Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Goldwyn Branch).

Edward G. Kuster's Court of the Golden Bough showing shops and entrance to the theater, 1924. Lewis Josslyn photo. From Carmel at Work and Play by Daisy F. Bostwick and Dorothea Castelhun, Seven Arts Press, Carmel, 1925, p. 86. (From my collection).

Having totally relocated his business activities from Los Angeles by 1924, Kuster's theater was built as part of his shopping development known as the Court of the Golden Bough on Ocean Avenue in Carmel's business district completed at the same time. (See above). He had previously commissioned Lee Gottfried to construct his personally-designed Norman-style residence (see below) next door to the five-acre Tor House spread of his former wife Una and Robinson Jeffers on Carmel Point.

During the four months after the earlier Theatre of the Golden Bough group photo was taken, Browne shuttled back and forth to Halcyon between play productions to be at Janson's side while she prepared to give birth to their love-child, Praxy on November 12th (see below). (Tingley, p. 145). Ellen's's aunt Borghild Janson, who also lived in Halcyon, found them a tiny house through the founder of The Temple of the People. Browne wrote, "members of his congregation denounced him for encouraging sin. He threatened them with excommunication; they called us 'The Holy Family'." (Browne, p. 278-9).

Browne and Janson used their Halcyon love-nest as a base while traveling up and down the California coast camping under the stars. Browne soon divorced Van Volkenberg at her insistence and moved into a new "redwood shack" built for Ellen by her parents near her aunt Borghild's house. (Browne, p. 282 and Tingley p. 145). Browne wrote of their child's conception,

While Browne was wrapping up his 1924 activities in Carmel the pregnant Ellen was performing at various Central Coast venues with Aunt Borghild and Schindler-Weston mutual friend Henry Cowell during October.

Browne and/or Van Volkenburg occasionally passed through Los Angeles in 1922-3 at which time the Schindlers possibly reconnected with them. Upon settling in Los Angeles Browne produced the occasional play (see above) and for the next two years taught at USC. Hearing that he was in the city, former students came back one by one to work with him. (Browne, p. 286). Appalled by Browne's squalid surroundings at USC, frequent Edward Weston portrait subject as early as 1916, Ruth St. Denis allowed him free use of her building and office while she was gone on a world tour. (Browne, p. 287). (For much more on Ruth St. Denis see my Bertha Wardell: Dances in Silence.)

As one of the movers and shakers of the planning effort, Pauline organized an event at Kings Road to help promote the cause. She arranged for Browne to lecture on Hermann Keyserling, likely on the occasion of the recent publication of his The Travel Diary of a Philosopher. (Author's note: Edward Weston often referenced Keyserling's diary in his Daybooks). Possibly accompanied by Ellen Janson to the soiree, Browne recollected, "And Pauline Schindler, brilliant, warm-hearted, bitter-tongued, who was trying to create a salon amid Hollywood's cultural slagheap, invited me to her home to lecture on Keyserling." (Browne, p. 287). Pauline excitedly wrote her mother of the salon, "[the party]...is going to be huge. We have never had more than a hundred guests before ... But this will be overflowing." (PGS letter to her mother, [n.d.] circa October, 1925. Cited in Sweeney, p. 96).

Besides frequently publishing Ellen Janson's poetry during her editorship of The Carmelite, Pauline also faithfully kept tabs on her family's comings and goings. For example she included a brief article reporting on Ellen and four-year old Maurice, Jr. passing through town and the whereabouts of Maurice, Sr. who was currently producing a play of George Bernard Shaw's in London. Pauline wrote of Browne,

Not long after Browne returned to England, Pauline had had enough of RMS's unfaithfulness and left Kings Road in late August of 1927 with son Mark for Carmel by way of Ojai and Halcyon. (PGS). She stopped long enough in Ojai to lick her wounds and explore the possibility of participating in the formation of the new Krotona Theosophist community being established by the followers of Krishnamurti. While there considering her next moves she was paid a comforting visit by the vacationing Dione Neutra and Galka Scheyer who were privy to the events surrounding her and Mark's departure. (Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 compiled and translated by Dione Neutra, Southern Illinois University Press, 1986, p. 167-8).

Accompanied by her parents, Pauline moved on to Halcyon where she was offered the use of Ellen Janson's house for the winter of 1927-8. Pauline stayed for a period of weeks to further convalesce from the trauma of her recent breakup. She was befriended and cared for by Janson's aunt Borghild and nearby Oceano Dunes denizen and poet Hugo Seelig. (Pauline Schindler letter to Betty Katz Kopelanoff, December 22, 1927, BK Papers). Before leaving for Carmel in mid-October Pauline also also most likely met John Varian, a prominent local Theosophist, and/or his neighbor Ella Young, a fellow Irish mystic poet discussed in more detail below. Varian was a meaningful mentor to both Pauline's piano idol Henry Cowell and Ansel Adams as also discussed later herein.

As she had done in Los Angeles, Pauline rapidly assimilated into the Carmel arts community upon her arrival. She soon began contributing an unsigned column titled "The Black Sheep" to the Carmel Pine Cone then under the editorship of Perry Newberry. Appearing 11 times between November 1927 and March 1928, she described it as a "new critical department which does not promise to behave itself too well," but that it would be, "young, fearless, honest, and vital." She focused mainly on music reviews, local issues and events. ("Life at Kings Road: As it Was 1920-1940," Sweeney, in The Architecture of R. M. Schindler, p. 104).

Through her association with the Pine Cone Pauline became involved with Carmel's new progressive weekly The Carmelite edited by Stephen A. Reynolds, for whom she penned the columns "Stage and Screen" and "With the Women" and other articles under her byline in early 1928. Pauline's April 25th "With the Women" column for example, reported on the annual P.T.A. conference in Salinas, the recent activities of Anne Martin, regional director of the Women's International League of Peace and Freedom founded by her Hull-House employer and mentor Jane Addams, and a meeting of 35 alumnae of her alma mater, Smith College, at Point Lobos.

Reynolds initially announced the weekly as, "a periodical which will without fear or favor give voice and light on both sides of a mooted question affecting the artistic or practical in village life." Reynolds, at odds with the entrenched positions of the Carmel Pine Cone, used his new vehicle as a way to publish politically-charged editorial jibes beginning in February 1928. Pauline quickly advanced to editorial assistant and and was anticipating becoming managing editor by mid-April. (Sweeney, p. 105). In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she wrote of The Carmelite as being, "a liberal-radical weekly, in whose pages the visiting or resident intelligentsia, from Lincoln Steffens to Robinson Jeffers, all had a word." After only 16 weeks at the helm, Reynold's turned over The Carmelite to Pauline after the May 30 issue.

"Painter, Poet, Pioneer," The Carmelite, October 21, 1928, p. 1. Johan Hagemeyer portrait of Charles Erskine Scott Wood.

Despite the unflagging boosterism of the well-connected Wood and Field and their attempts to raise funds for the theater project, promised pledges of support from others failed to materialize. (Browne, p. 270). The Brownes packed their bags again in 1924 and headed for Carmel where one of their San Francisco students, Edward Kuster, had founded an acting school and the Theatre of the Golden Bough. (See below). The Golden Bough opened in June 1924 with the Brownes producing five plays before the end of the year. (Hilliard, Helen, "Eyes of Carmel Watch Paint and Political Pots," Oakland Tribune, April 8, 1924, p. 11). (For much more on this very eventful summer see my "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924").

Edward Kuster's Theatre of the Golden Bough under construction, Carmel, 1923. Photograph courtesy of the Harrison Memorial Library Collection.

Originally a prominent lawyer from Los Angeles, Kuster was formerly married to Una Lindsay Call before she met and fell in love with Robinson Jeffers who would soon thereafter begin his informal reign as Carmel's poet laureate. The Kuster's scandalous breakup was reported as a "queer love triangle" in a series of articles appearing in 1912-13 in the Los Angeles Times. (See for example, "Parents Wash Hands of It; "His Own Affair," says Poet Jeffers's Mother; Mrs. Kuster Defended as the Scapegoat of Clique," Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1913, p. II-1). (For much more on Jeffers see my Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence).

From Carmel-By-The-Sea by Monica Hudson, Arcadia, 2006, p. 85. Note the multi-talented Kings Road salon attendee, actor and noted city planner Carol Aronovici on the left who, while wearing his City Planner hat, collaborated with Schindler and Richard Neutra on the 1928 Richmond, California Civic Center project and other projects under their Architectural Group for Commerce and Industry (AGIC) partnership.

Browne recollected,

"[Kuster] proposed to build a playhouse in Carmel; it would have a full sky-dome (see below), the first in the country. The three of us spent months pulling his plans to pieces; the Theatre of the Golden Bough was to be the best equipped and most beautiful in America. It was. Kuster invited us to open it with a play [Mother of Gregory] written by me (see below), to run a summer-school there, and to direct it afterwards as an art-theatre." (Browne, p. 271).

A scene from Maurcice Browne's "Mother of Gregory," Theatre of the Golden Bough, Carmel, June 6-7, 1924. Theatre Arts Monthly, September, 1924, p. 585. Josselyn photo.

Carmel theater productions in 1924. From Carmel - its poets and peasants by Stephen Allen Reynolds, Bohemian Press, Carmel-by-the-Sea, 1927, p. 14. (Author's note: Reynolds was the founder of The Carmelite in February and turned publication over to Pauline Schindler after tiring of the enterprise in May 1928).

Theatre of the Golden Bough, Carmel, 1925. From the Full Wiki.

Ruth St. Denis congratulatory note to Edward Kuster upon the opening of the Theatre of the Golden Bough, 1924. Photographer unknown. From Carmel-by-the-Sea by Monica Hudson, Arcadia, 2006, p. 85 via the Harrison Memorial Library Local History Collection. (For much more on Ruth St Denis see my "Bertha Wardell: Dances in Silence").

Kuster and his second wife Edith had earlier been involved with the renowned Ruth St. Denis Dance Company and after she teamed up with Ted Shawn, Kuster helped them form the Denishawn Dance Center in Los Angeles. The above photograph expresses her appreciation for his work and dedication to the theater arts. St. Denis shrewdly incorporated her patron's wife Edith in one of her marketing brochures (see below) touting her as "One of the most charming young society matrons of Los Angeles, who has given great pleasure at many benefits and charity performances with her Denishawn dances." ("Denishawn: A University of the dance. World famous in its third season," p. 9, Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Goldwyn Branch).

Denishawn dancer Edith Emmons Kuster as "Ladye Farye". "Denishawn: A University of the dance. World famous in its third season," p. 9. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Goldwyn Branch).

Having totally relocated his business activities from Los Angeles by 1924, Kuster's theater was built as part of his shopping development known as the Court of the Golden Bough on Ocean Avenue in Carmel's business district completed at the same time. (See above). He had previously commissioned Lee Gottfried to construct his personally-designed Norman-style residence (see below) next door to the five-acre Tor House spread of his former wife Una and Robinson Jeffers on Carmel Point.

Kuster Residence, Carmel Point, 1920. Photographer unknown. Photo scanned from Carmel: A History in Architecture by Kent Seavey, Arcadia, 2007, p. 68. Courtesy of Pat Hathaway, California Views.

Ellen Janson Browne and son Praxy ca. 1926. Photographer unknown. (Tingley, Donald F., "Ellen Van Volkenburg, Maurice Browne and the Chicago Little Theatre," Illinois State Historical Society Journal, Autumn, 1987, p. 144.

Browne and Janson used their Halcyon love-nest as a base while traveling up and down the California coast camping under the stars. Browne soon divorced Van Volkenberg at her insistence and moved into a new "redwood shack" built for Ellen by her parents near her aunt Borghild's house. (Browne, p. 282 and Tingley p. 145). Browne wrote of their child's conception,

"He was gotten, willfully, at noon of a still burning August day on one of those beaches; we both knew that he would be a male. His mother and I, living in a dream world, believed that once he was surely conceived she could go happily forth into the world alone, carrying him, and I return to my work with Nellie Van." (Browne, pp. 278-9).

"Henry Cowell, Borghild and Ellen Janson Browne, her niece, gave a series of concerts in October in San Luis Obispo, Atascadero, Santa Maria and Lompoc. Of course you all know of Henry's work, both in European and American cities, and Borghild's beautiful voice has been too often spoken of to need further description, but you have not been told of Ellen. She is a young poetess of the modern school and not only writes excellent verse, but recites it in a delightfully deep, vibrant voice that causes delicious thrills up and down one's spine and makes one feel really one with the character of whom her verse is telling. At the various concerts Henry played, Borghild sang, and Ellen recited, so you may believe that they were quite interesting." (Temple of the People Family Letter No. 1, Vol. III, p. 3).The restless Browne continued his vagabond ways and moved his center of operations to Los Angeles after his and Kuster's successful 1924 season in Carmel. Around this time Browne had a stopover in Halcyon to spend some time with the pregnant Janson where he also read Jeffers' recently published Tamar which prompted a letter of praise to the poet and his reply, "...That you should read "Tamar" through such a divine hazard, in the oasis by Santa Maria [Halcyon], is more luck than any writer deserves..." (Letter from Jeffers to Browne, February 11, 1925, from The Selected Letters of Robinson Jeffers, 1897-1962 edited by Anne N. Ridgeway, Johns Hopkins Press, 1968, p. 33).

Announcement for performances of two of Browne's plays. Los Angeles Times, December 14, 1924.

Browne and/or Van Volkenburg occasionally passed through Los Angeles in 1922-3 at which time the Schindlers possibly reconnected with them. Upon settling in Los Angeles Browne produced the occasional play (see above) and for the next two years taught at USC. Hearing that he was in the city, former students came back one by one to work with him. (Browne, p. 286). Appalled by Browne's squalid surroundings at USC, frequent Edward Weston portrait subject as early as 1916, Ruth St. Denis allowed him free use of her building and office while she was gone on a world tour. (Browne, p. 287). (For much more on Ruth St. Denis see my Bertha Wardell: Dances in Silence.)

Maurice Browne Theatre promotional fund-raising letter from Thomas H. Elson and G. G. Detzer to the Schindlers, August 24, 1925. Courtesy UC Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

Despite Browne's philandering ways, Van Volkenberg continued her professional relationship and they were soon back working together on projects such as an April, 1925 Maurice Browne Players performance at the Wilshire Ebell Theater of Browne's "Mother of Gregory" first performed in Carmel the previous summer. ("Ebell Program or Month Out", Los Angeles Times, April 23, 1925, p. I-7.) Throughout 1925 momentum began to build for construction of a little theater for Los Angeles to house the newly formed Maurice Browne Theatre Association. During the summer a consortium of sponsors began a $125,000 fund-raising campaign to finance the construction of a new theater and classrooms for the project. RMS couldn't help but hope that the theater commission would come his way. (See above solicitation letter for example).

Maurice Browne Theatre Association season-ticket subscription form, 1926. Courtesy UC Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

As one of the movers and shakers of the planning effort, Pauline organized an event at Kings Road to help promote the cause. She arranged for Browne to lecture on Hermann Keyserling, likely on the occasion of the recent publication of his The Travel Diary of a Philosopher. (Author's note: Edward Weston often referenced Keyserling's diary in his Daybooks). Possibly accompanied by Ellen Janson to the soiree, Browne recollected, "And Pauline Schindler, brilliant, warm-hearted, bitter-tongued, who was trying to create a salon amid Hollywood's cultural slagheap, invited me to her home to lecture on Keyserling." (Browne, p. 287). Pauline excitedly wrote her mother of the salon, "[the party]...is going to be huge. We have never had more than a hundred guests before ... But this will be overflowing." (PGS letter to her mother, [n.d.] circa October, 1925. Cited in Sweeney, p. 96).

A few months later Browne formally announced that Los Angeles would be the production headquarters for his Maurice Browne Theatre Association with offices to be located in the Transportation (aka Subway Terminal) Building and that he would be joined by Van Volkenberg. ("Nationally Known Producer Chooses City as Production Headquarters for Little Plays", Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1927, p. 23). The following week another lengthy article reported on the specifics of the association's planning efforts and the plays Browne currently had in rehearsal. The members of the Sponsors' Committee were listed and included as chairman Thomas H. Elson, G. G. Detzer, Mrs. R. M. Schindler and others. (Little Theater Planned, Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1926, p. 21).

A banquet at the Men's City Club a few nights later feted Browne and Van Volkenburg with numerous testimonial speeches and telegrams from around the country wishing the venture well. ("Announces Premiere Production," Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1926, p. I-10). Browne reminisced,

"A great banquet was planned in my honour; every theatrical celebrity whom I knew in America and Europe was invited to attend as a guest of honour; an astonishingly large number sent messages of goodwill; some even accepted. The realtor danced round Ruth St. Denis' office: "With these names behind us the theatre is as good as built." It was all so splendiferous that I telegraphed Nellie Van to come to the banquet; she sat beside me; the speeches made us feel that we had not lived in vain. Finally our evening came to its end. As I was leaving, the chairwoman of the Publicity Committee unostentatiously handed me an envelope. "A cheque on account," I thought, "how charming:" and thanked her warmly. When I got home I opened the envelope. It contained the bill for printing, postage, stationery, telephone, telegrams, table decorations and dinner for the guests of honour. Grinning wrily, Nellie Van returned to Seattle. My students and I gave performances anywhere - schoolrooms, tents, barns - where a ten-dollar note could be earned toward paying that bill: dollar by dollar we paid it to the last cent. Then I spat savagely and straight into the streets of Los Angeles and, worn out by the interminable conflicts within myself, the interminable struggle to establish a theatre which mattered, the interminable inability to pay for it, said goodbye to my theatric dreams." (Browne, p. 288).

Browne dejectedly left for San Francisco where he licked his wounds over the next nine months and during which time he and Janson were married. ("Maurice Browne and Seattle Girl Married," Carmel Cymbal, March 9, 1927, p. 1). Browne reflected before returning alone "back to the womb" to England, "After fifteen years' continuous struggle I had failed in the theatre; I had failed as a husband twice; I had failed as a father." Browne later recollected Pauline's unflagging support, "Twenty-four years later, during my farewell visit to America, Pauline lent me the house [Kings Road]. There I forgathered again daily with these and other old friends. Pauline was battling against political, Grace against educational, Sophie against social stupidity." (Browne, p. 287).

A couple years after returning to England, the perseverant Browne was back on his feet and doing well enough to send for Ellen and Praxy, convincing her that an English education would be better for the boy. Pauline published in The Carmelite Janson's preparations to rejoin Maurice,

"It has been a very bad theatre season in New York this winter with many houses "dark." Yet, "Wings Over Europe," a play without a woman in it, written by Maurice Browne, once director of the Theatre of the Golden Bough, continues week after week. Meanwhile, Mrs Browne, known chiefly, and often to the readers of the Carmelite, as a poet, and a very good one, puts the final touches to her novel, and is about to set sail with the small round Maurice Browne aged five, to England where he is to be educated. ("Personal Bits," The Carmelite, February 27, 1929, p. 3).

Pauline later published excerpts of Ellen's chronicle of her and Praxy's voyage to England during the summer of 1929. (Janson, Ellen, "Journey Southward," The Carmelite, August 14, 1929, p. 10). Browne's improving finances also enabled commissioning noted sculptor Jacob Epstein to do a bust of Ellen. (See below). His "rags-to-riches" success story was front page news in Carmel in 1931. ("Maurice Browne in London," The Carmelite, August 18, 1931, p. 1).

"Smiling Head," Ellen Janson, bronze bust, 1931, by Jacob Epstein. Courtesy Christie's. (Many thanks to MAK Schindler Scholar and artist-in-residence Kostis Velonis for bringing this bust to my attention. Kostis is curating an exhibition on Janson for the Schindler House for September 2012).

"In Carmel he remains a memory and an influence, for Morris Ankrum, George Ball, and many others here busy with the stage have had their first dramatic training under the direction of this intense and passionate artist." (Schindler, Pauline, "Maurice Browne in a Second Edition," The Carmelite, July 11, 1928, p. 2)

Morris Ankrum, Carmel, August 16, 1924. Photo by Johan Hagemeyer. Courtesy Bancroft Library, U. C. Berkeley.

Not long after Browne returned to England, Pauline had had enough of RMS's unfaithfulness and left Kings Road in late August of 1927 with son Mark for Carmel by way of Ojai and Halcyon. (PGS). She stopped long enough in Ojai to lick her wounds and explore the possibility of participating in the formation of the new Krotona Theosophist community being established by the followers of Krishnamurti. While there considering her next moves she was paid a comforting visit by the vacationing Dione Neutra and Galka Scheyer who were privy to the events surrounding her and Mark's departure. (Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 compiled and translated by Dione Neutra, Southern Illinois University Press, 1986, p. 167-8).

Accompanied by her parents, Pauline moved on to Halcyon where she was offered the use of Ellen Janson's house for the winter of 1927-8. Pauline stayed for a period of weeks to further convalesce from the trauma of her recent breakup. She was befriended and cared for by Janson's aunt Borghild and nearby Oceano Dunes denizen and poet Hugo Seelig. (Pauline Schindler letter to Betty Katz Kopelanoff, December 22, 1927, BK Papers). Before leaving for Carmel in mid-October Pauline also also most likely met John Varian, a prominent local Theosophist, and/or his neighbor Ella Young, a fellow Irish mystic poet discussed in more detail below. Varian was a meaningful mentor to both Pauline's piano idol Henry Cowell and Ansel Adams as also discussed later herein.

Through her association with the Pine Cone Pauline became involved with Carmel's new progressive weekly The Carmelite edited by Stephen A. Reynolds, for whom she penned the columns "Stage and Screen" and "With the Women" and other articles under her byline in early 1928. Pauline's April 25th "With the Women" column for example, reported on the annual P.T.A. conference in Salinas, the recent activities of Anne Martin, regional director of the Women's International League of Peace and Freedom founded by her Hull-House employer and mentor Jane Addams, and a meeting of 35 alumnae of her alma mater, Smith College, at Point Lobos.

Reynolds initially announced the weekly as, "a periodical which will without fear or favor give voice and light on both sides of a mooted question affecting the artistic or practical in village life." Reynolds, at odds with the entrenched positions of the Carmel Pine Cone, used his new vehicle as a way to publish politically-charged editorial jibes beginning in February 1928. Pauline quickly advanced to editorial assistant and and was anticipating becoming managing editor by mid-April. (Sweeney, p. 105). In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she wrote of The Carmelite as being, "a liberal-radical weekly, in whose pages the visiting or resident intelligentsia, from Lincoln Steffens to Robinson Jeffers, all had a word." After only 16 weeks at the helm, Reynold's turned over The Carmelite to Pauline after the May 30 issue.

Under Pauline's leadership The Carmelite became much more than a local newspaper. It was a leading-edge progressive publication reporting on many of the left-leaning issues of the day, the local arts and literary scene and reviews of cultural events in San Francisco and even far away Los Angeles. She used the paper to express her own artistic and political opinions and promote her personal interests and the work of her friends. She was truly in her element during this period of her life. In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she stated that she wrote about half the paper which is probably an understatement based on the issues in my collection. (Sweeney, p. 105). She also featured many of the people from her Los Angeles circle of friends, Kings Road salon participants and former tenants such as Edward Weston, Henrietta Shore, John Bovingdon, Carol Aronovici, Ellen Janson, Galka Scheyer, Richard and Dione Neutra and many others. (PGS).

Johan Hagemeyer Studio, Carmel. Photo courtesy OAC and U.C. Berkeley Bancroft Library, Johan Hagemeyer Photo Collection.

Tired of city life, Weston moved to Carmel in early January 1929, trading spaces from a temporary stay in fellow photographer Johan Hagemeyer's studio in San Francisco to renting his Carmel summer studio. (See above). Hagemeyer, a close friend of Margrethe Mather and Weston since early 1918, opened a portrait studio in San Francisco in 1923 and also built the summer studio in Carmel in 1924 which quickly became a meeting place for artists and intellectuals. For example, in his 1925 publication Carmel - its poets and peasants, Pauline's predecessor as editor of The Carmelite, Stephen Allen Reynolds, devoted half a page of glowing praise to Hagemeyer and dubbed him "Sandburg of the camera." Pauline's article "Edward Weston on the Way" published six months after taking over The Carmelite reins from Reynolds announced the impending arrival of her and RMS's close friend since 1921 Walt Whitman School days and from their Kings Road salons and soirees. Weston also described the move at length in his Daybooks. (Daybooks, pp. 99-108).

Pauline also often published Hagemeyer's photos and his sister-in-law Dora's poetry in The Carmelite (see above and earlier Hagemeyer portrait cover portrait of Charles Erskine Scott Wood for example). Weston and Hagemeyer had a falling out in late 1929 over the studio lease agreement prompting Weston to move his studio four blocks to the west to the Seven Arts Building adjacent to the Court of the Golden Bough and across the street from the new Bernard Maybeck-designed Harrison Memorial Library on Ocean Avenue in the heart of Carmel upstairs from The Carmelite's offices in January 1930 (see below). (PGS).

.jpg)

Left, Johan Hagemeyer, 1928. Edward Weston portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents. Right, Johan Hagemeyer and Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, 1921. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 85.

Pauline properly introduced Weston to Carmel's bohemian community at a reception for the Kedroff Quartet following much heralded their performance (see Above). Weston's Daybook entry reads,

Weston soon began an affair with Johan's former assistant Sonya Noskowiak which quickly blossomed into a full-blown relationship. She moved into his studio and in return for household chores, surrogate mother duty for his visiting sons, and darkroom assistance, Edward gave her a camera and began to teach her the fundamentals of photography. Sonya proved to be a natural and was quickly accepted by Edward and his coterie, including son Brett, another disciple Willard Van Dyke, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, and a few others when they formed Group f/64 and had their inaugural exhibition at San Francisco's M. H. de Young Museum in 1932.

Nellie Cornish returns to the story with a visit to Carmel and Weston's studio in the summer of 1930. It seems likely that she had been informed of Weston's work by their mutual longtime friend Imogen Cunningham. Possibly combining business with pleasure, Cornish could have been scouting for music, art and drama teachers in the talent-rich Monterey Peninsula. Weston wrote of the meeting, "Yesterday I sold my old "Circus Tent," - then later my favorite new pepper, - its first sale, to Miss Cornish, who has a school - I think of music - in Seattle." (Daybooks, August 17, 1930, p. 182). This meeting laid the groundwork for Cole's matriculation at the Cornish School in the fall of 1937 where he would cross paths with Xenia Kashevaroff (see below) and John Cage who joined the faculty the following year.

After having studied art briefly at Reed College in Portland, Xenia became a disciple of Weston's close friend Henrietta Shore back in Carmel in the fall of 1932. Shore and Weston met in Los Angeles 1927 through mutual friend Peter Krasnow which by association brought her into the Schindler's Kings Road circle. Pauline featured her work on the cover of The Carmelite in the summer of 1928 in conjunction with an exhibition of her work at the Hagemeyer Studio. (See above).

The following spring, the precocious Xenia's work (see below for example) was exhibited at San Francisco's de Young Museum alongside drawings and lithographs by Shore, photography by Edward and Brett Weston, Margrethe Mather, and many Group f/64 members including Sonya Noskowiak, Willard Van Dyke, Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams and an architectural exhibition of work by Rudolph Michael Schindler which likely included Edward Weston photos of his Lovell Beach House and Brett Weston photos of his Wolfe House. (“Art and Artists: Architect Holding Exhibit at Museum... A gallery of modern photographs...” Berkeley Daily Gazette (13 April 1933): 7.)

Schindler, Pauline G., "Weston on the Way," The Carmelite, December 28, 1928, p. 2. (From my collection).

Hagemeyer, Dora, "Christ-Birth," Bruton, Esther, "Valdez, New Mexico," woodcut, 1928, The Carmelite, March 20, 1929, front page. (From my collection).

Pauline also often published Hagemeyer's photos and his sister-in-law Dora's poetry in The Carmelite (see above and earlier Hagemeyer portrait cover portrait of Charles Erskine Scott Wood for example). Weston and Hagemeyer had a falling out in late 1929 over the studio lease agreement prompting Weston to move his studio four blocks to the west to the Seven Arts Building adjacent to the Court of the Golden Bough and across the street from the new Bernard Maybeck-designed Harrison Memorial Library on Ocean Avenue in the heart of Carmel upstairs from The Carmelite's offices in January 1930 (see below). (PGS).

Seven Arts Building, Carmel, 1926. Herbert Heron, owner, Albert B. Coats, architect. Photographer unknown. Photo scanned from Carmel: A History in Architecture by Kent Seavey, Arcadia, 2007, p. 68. Courtesy of Pat Hathaway, California Views. Weston's studio was in the upper right dormer from1930-35.

.jpg)

Left, Johan Hagemeyer, 1928. Edward Weston portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents. Right, Johan Hagemeyer and Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, 1921. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 85.

Pauline properly introduced Weston to Carmel's bohemian community at a reception for the Kedroff Quartet following much heralded their performance (see Above). Weston's Daybook entry reads,

"To the Kedroff Quartet: the most exquisite vocal music I have heard. The folk-songs were especially thrilling, and the Strauss Waltz! ... After, I went with Pauline to a reception for the Quartet, and there met Carmel "society," everyone that I should meet I suppose! I have certainly been flatteringly presented to Carmel with many newspaper columns [by Pauline in The Carmelite] of flowery praise. Once could easily become "a big toad in a little puddle" here. Not my intention!" (Daybooks, March 16, 1929, pp. 112-3).

Pauline kept steady tabs on the comings and goings of Weston and various combinations of visiting sons in the pages of The Carmelite. For example she reported on a serious Brett Weston accident while riding with long-time Weston patron and book designer Merle Armitage. Brett suffered a compound fracture when his horse threw him and rolled over onto his leg. ("Personal Bits", by Pauline Schindler, The Carmelite, March 27, 1929, p. 3).

Sonya Noskowiak, ca. 1929. Edward Weston photo. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Weston soon began an affair with Johan's former assistant Sonya Noskowiak which quickly blossomed into a full-blown relationship. She moved into his studio and in return for household chores, surrogate mother duty for his visiting sons, and darkroom assistance, Edward gave her a camera and began to teach her the fundamentals of photography. Sonya proved to be a natural and was quickly accepted by Edward and his coterie, including son Brett, another disciple Willard Van Dyke, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, and a few others when they formed Group f/64 and had their inaugural exhibition at San Francisco's M. H. de Young Museum in 1932.

Nellie Cornish returns to the story with a visit to Carmel and Weston's studio in the summer of 1930. It seems likely that she had been informed of Weston's work by their mutual longtime friend Imogen Cunningham. Possibly combining business with pleasure, Cornish could have been scouting for music, art and drama teachers in the talent-rich Monterey Peninsula. Weston wrote of the meeting, "Yesterday I sold my old "Circus Tent," - then later my favorite new pepper, - its first sale, to Miss Cornish, who has a school - I think of music - in Seattle." (Daybooks, August 17, 1930, p. 182). This meeting laid the groundwork for Cole's matriculation at the Cornish School in the fall of 1937 where he would cross paths with Xenia Kashevaroff (see below) and John Cage who joined the faculty the following year.

Xenia Kashevaroff, Carmel, 1931. Edward Weston photograph. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

The first mention of Xenia Kashevaroff (see above) in Weston's Daybooks is in November 1932, just as his first book produced by Merle Armitage was going to press and just before the inaugural Group f/64 opening in San Francisco. He wrote, "My desk is cleared of unanswered letters, orders to date all printed. So a few days ago Henry [Henrietta Shore] drove Xenia, Sonya and myself to Oliver's cacti garden in Monterey. There was amazing material and I worked hard and well." (Daybooks, November 8, 1932, p. 264). This entry indicates that Xenia, the youngest of six daughters of the Russian Orthodox Bishop in Juneau, Alaska, Alexander Kashevaroff, was already known to Weston.

Ed Ricketts, ca. 1930. Photo by Bryant Fitch, 1937. From A Fire in the Mind: The Life Story of Joseph Campbell by Stephen and Robin Larsen, Doubleday, 1991, p. 171).

A couple years earlier, while living with her sister Sasha and still a senior at Monterey High School, Xenia had a steamy love affair with the then married with children, 34-year old marine biologist Ed Ricketts (see above) on whom lifelong friend John Steinbeck's character Doc in Cannery Row was based. Further provenance of an earlier meeting is evidenced by the six clothed Weston portraits of Xenia in the collection of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art being dated 1931. A January 1933 entry relates Weston's late 1932 liaison with X. before leaving for Los Angeles to sign copies of his new book. He philosophized while Sonya traveled to Los Angeles with his equally philanderous friend and patron Merle Armitage,

A Monterey Peninsula intellectual-social circle developed in the early 1930s which included Xenia, her sister Sasha and husband Jack Calvin, her sister Natalya and husband Ritchie Lovejoy, Ed Ricketts, Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Steinbeck and wife Carol, and noted mythologist, writer and lecturer Joseph Campbell. Steinbeck (see below) married Carol Henning and moved to Pacific Grove in 1930 where he quickly befriended kindred spirit Ricketts. After leaving his position as a writing instructor at Stanford in 1929, Jack and Sasha, whom he met on a research trip to Juneau, moved to Carmel and began collaborating with Ricketts on his groundbreaking Between Pacific Tides. (See above and below). Joseph Campbell moved next door to Ricketts in Pacific Grove in 1932. This philosophizing, fun-loving group shared jointly-prepared meals, read each other's work, and raucously partied plied with doctored lab-quality alcohol provided by Ricketts. Campbell quickly became infatuated with Steinbeck's wife Carol which essentially ended their friendship.

Artist-writer Lovejoy met Natalya after he came to Carmel to visit his former Stanford teacher and eventually became Calvin's brother-in-law. (See above). Unsurprisingly, Calvin and Lovejoy were both in Pauline Schindler's social circle as they were listed in attendance with her at a party in honor of Weston's recent move to Carmel hosted by fellow photographer Roger Sturtevant (see opening group photo) and his wife. The article read,

Lovejoy eagerly joined in on the collaboration on Ricketts' book providing over 100 illustrations to the final publication. Thus, the three Kashevaroff sisters were romantically involved with the principals in the book's publication. The culmination of years of field research and collaboration with his friends, Rickett's masterpiece is still widely regarded as a classic work in marine ecology and is now in its fifth edition.

"Maybe Sonya is having the adventure. I hope so; then my conscience might be eased. But am I not expressing that thing one is supposed to have, - a conscience? Actually, I have never felt guilt over my philandering; only a desire not to be discovered for her sake; not yet at least. And I could feel quite as guilty toward L., from whose arms I went to H. in L. A. To be sure it was unpremeditated, and we had both reached a delightful intoxication but that does not absolve me from the guilt I should feel, - and don't! Yes, and before going south I made love to both S. and X.! Am I then so weak that I fall for every petticoat? Am I so oversexed that I cannot restrain myself? Neither question can be dismissed with a "yes." First, I can go long periods with no desire, no need; then I see the light in a woman's eyes which calls me, and can find no good reason - if I like her - not to respond. I have never deliberately gone out of my way to make a conquest, to merely satisfy sex needs. It amounts to this; that I was meant to fill a need in many a woman's life, as in turn each one stimulates me, fertilizes my work. And I love them all in turn, at least it's more than lust I feel, for the months, weeks, or days we are together. Maybe I flatter myself, but so I feel. So what will you answer to this, Sonya?- (Daybooks, January 18, 1933, p. 267).

Between Pacific Tides by Edward F. Ricketts and Jack Calvin, Foreword by John Steinbeck, Line Drawings by Ritchie Lovejoy, Stanford University Press.

A Monterey Peninsula intellectual-social circle developed in the early 1930s which included Xenia, her sister Sasha and husband Jack Calvin, her sister Natalya and husband Ritchie Lovejoy, Ed Ricketts, Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Steinbeck and wife Carol, and noted mythologist, writer and lecturer Joseph Campbell. Steinbeck (see below) married Carol Henning and moved to Pacific Grove in 1930 where he quickly befriended kindred spirit Ricketts. After leaving his position as a writing instructor at Stanford in 1929, Jack and Sasha, whom he met on a research trip to Juneau, moved to Carmel and began collaborating with Ricketts on his groundbreaking Between Pacific Tides. (See above and below). Joseph Campbell moved next door to Ricketts in Pacific Grove in 1932. This philosophizing, fun-loving group shared jointly-prepared meals, read each other's work, and raucously partied plied with doctored lab-quality alcohol provided by Ricketts. Campbell quickly became infatuated with Steinbeck's wife Carol which essentially ended their friendship.

Between Pacific Tides by Edward F. Ricketts and Jack Calvin, Foreword by John Steinbeck, Line Drawings by Ritchie Lovejoy, Stanford University Press, Third Edition, 1960.

Ritchie and Natalya Kashevaroff Lovejoy playing in the backyard of the Steinbeck's house, Pacific Grove, ca. 1935. Photographer unknown. From Renaissance Man of Cannery Row: The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts edited by Katherine A. Rodger, University of Alabama Press, 2002, p. 100.

Artist-writer Lovejoy met Natalya after he came to Carmel to visit his former Stanford teacher and eventually became Calvin's brother-in-law. (See above). Unsurprisingly, Calvin and Lovejoy were both in Pauline Schindler's social circle as they were listed in attendance with her at a party in honor of Weston's recent move to Carmel hosted by fellow photographer Roger Sturtevant (see opening group photo) and his wife. The article read,

“Mr. and Mrs. Roger Sturtevant entertained a number of friends Saturday evening at their home in Carmel. Mr. Edward Weston, the noted photographer, showed a number of his recent camera studies, following which the guests danced until a late hour. Those present included Mr. and Mrs. Hans Ankersmit, Miss Nancy Clark, Miss Tommi Thomson, Miss Tilly Polak, Mrs. Tilly Polak, Mrs. Pauline Schindler, George Norhland, Eddie O’Brien, Kelley Clark, Jack Calvin, Richard Lovejoy, Clay Otto, and many others.” (“The Village News-Reel: Sturtevants Entertain at Interesting Evening.” The Carmel Pine Cone 15:5 (1 February 1929): 14).

Lovejoy eagerly joined in on the collaboration on Ricketts' book providing over 100 illustrations to the final publication. Thus, the three Kashevaroff sisters were romantically involved with the principals in the book's publication. The culmination of years of field research and collaboration with his friends, Rickett's masterpiece is still widely regarded as a classic work in marine ecology and is now in its fifth edition.

John Steinbeck, ca.1932. Photo by Sonya Noskowiak. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents. (Author's note: Neil Weston and friend Sam Coblentz built a seventeen foot sloop, "The Goon" which was later purchased by Steinbeck. See Laughing Eyes A Book of Letters Between Edward and Cole Weston, 1923-1946, p. 42).

Jack and Sasha moved to Sitka in 1931 and the following summer sailed their 33-foot boat, the Grampus (see below), as far south as Tacoma. To break his close friends Campbell and Steinbeck out of their respective funks over Joseph's and Carol's affair, Ricketts arranged for himself and Campbell to hook up with them for a specimen-collecting voyage to Juneau. Campbell assisted Ricketts in his collections, and the two young men engaged in a running discussion about philosophy, human experience, native cultures and the deep meaning of the varied totems they encountered on their journey to Alaska. Their bonding on this trip forged a friendship that would last until the end of Ricketts' life in 1948.

Grampus and Crew, Sitka, Alaska, August 1932. Photographer unknown. From Renaissance Man of Cannery Row: The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts edited by Katherine A. Rodger, University of Alabama Press, 2002, p. 98.

In Alaska to visit relatives, Xenia was staying at her uncle's cabin in Sitka when the Grampus anchored in mid-August. She first met a nude Joseph Campbell while topless sunbathing on the Sitka shoreline where he swam from the Grampus. Despite their strong mutual attraction and continued nude sun-bathing they decided to keep their relationship Platonic. Xenia decided to accompany the "metaphysical vagabonds" back to Juneau where the rest of the family resided. Campbell was greatly impressed with Father Kashevaroff's combination Russian-Tlingit Mass and the Indians in his congregation and later his Siberian Shaman and Alaskan history stories. Xenia recalled, "Joe made a hit with my father because he picked up the balalaika and immediately began to play it like an old professional." After enjoying the freedom of nudity with Xenia the previous weeks, Campbell lamented in his journal about human constrictions such as having to be "conventionally dressed" for the return trip to Seattle aboard a commercial liner. (For more see A Fire in the Mind: The Life Story of Joseph Campbell by Stephen and Robin Larsen, Doubleday, 1991).

"The Bullfight" by Henrietta Shore, Mexico, 1927, The Carmelite, July 25, 1928, p. 1.

After having studied art briefly at Reed College in Portland, Xenia became a disciple of Weston's close friend Henrietta Shore back in Carmel in the fall of 1932. Shore and Weston met in Los Angeles 1927 through mutual friend Peter Krasnow which by association brought her into the Schindler's Kings Road circle. Pauline featured her work on the cover of The Carmelite in the summer of 1928 in conjunction with an exhibition of her work at the Hagemeyer Studio. (See above).

Nude, Xenia Kashevaroff, Carmel, 1933. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

A notorious ladies' man like Ricketts, Weston seems to have begun his affair with Xenia sometime after her relationship with Ricketts ended. He likley took the above and below and other nudes of Xenia in February 1933 with his new 4 X 5 Graflex camera. (Daybooks, February 2, 1933, p. 270). A few weeks after this sitting Weston described in the Daybooks an anonymous sexual liaison that has Xenia's DNA all over it.

"How I am going to take proper care of three women remains to be seen. I place my difficulties in the hands of the good Pagan Gods. The coming into my life of - was dramatically sudden. I had always felt that it would happen sometime; I have been drawn to her for three years, - since she was a child - albeit a mature one - of sixteen. And she was attracted to me, that was evident. I sensed her virginal desire for experience, and wanted to initiate her, but at the time there were - or I thought so - too many difficulties. Then she went away, returning after a year or so, - with experience. [Ed Ricketts?]. Seeing the light in her eyes, I soon found a way to be with her alone. There was no resistance to the first kiss. But still there were difficulties, - or again I thought so; Carmel is so small a place! Matters drifted along, with only an occasional surreptitious embrace, - until Saturday night (2:25) when - slightly tight - "bingy" she called her condition - took the initiative and came to me. I had just returned to the studio, tired from a sitting of Robin [Jeffers], had turned back my bedcovers, when a tap-tap came on my door. I turned on the lights and quickly turned them off, seeing who stood there, and sensing at once, why. She was delightfully the child, though a very poised one, in explaining her call. She was delicately apologetic for coming to me, yet direct and frank; - not the least brazen. She knew what she wanted, and what I wanted - but she knew my difficulties and so cleared the way. I assured - that having acquired knowledge through experience it was obviously a duty - and a pleasant one to hand on to her all that I knew! So we wasted no more time in talk. I am not exaggerating when I say, that she had the most beautiful breasts I have ever seen or touched; breasts such as Renoir painted, swelling without the slightest sag, - high, ample, firm. - stayed the night. We slept but little. She moved me profoundly. A dear child, with a desire to learn, no inhibitions and much passion." (DB, February 26, 1933, p. 272).

Nude, Xenia Kashevaroff, Carmel, 1933. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Xenia Kashevaroff, Russian Orthodox Church, Fort Ross, CA, watercolor, ca. 1932. Courtesy Alaska's Digital Archives.

Eileen Eyre, 1927. Photo by former Carmelite Arnold Genthe. From AMICA.

Searching for an exhibition venue to save face after being excluded from the upcoming Museum of Modern Art's "Modern Architecture International Exhibition" scheduled August stopover at Bullock's Wilshire during the 1932 Olympics, Schindler had his eyes on San Francisco where he had an admiring "fan club." He successfully landed the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park through his romantic connection to Eileen Eyre, head of a dance troupe which formerly included another sometime girlfriend Harriet Freeman. Schindler wrote to Eyre,

"I am trying to arrange for an exhibit of my work in San Francisco - and thought under other places the Legion of Honor Palace (is that the right name?) Do not quite know how to address your friend [Director Lloyd LaPage Rollins] there (is he still both there & friend?) Aren't you coming down again? - Or wouldn't I know about it?" (RMS to Eileen Eyre, April 17, 1932, de Young Museum Exhibition Archives. Author's note: This exhibition was one of the last for Rollins who was soon ousted by the conservative board for his less than discreet extra-curricular affairs.)

In a message written on Schindler's letter forwarded to Rollins Eyre wrote,

"This just came to me. You may recall meeting Schindler last spring or fall at [Marjorie] Eaton's ranch. He is quite poor & I guess must be rather desperate. But as he worked years with Frank Lloyd Wright he must know Modern Architecture. I simply gave him your name& also Gutherie's - thinking one of you might be interested..." (Eileen Eyre to Lloyd LaPage Rollins, ca. April 1932. de Young Museum Exhibition archives. Author's note: Marjorie Eaton was a close friend of the Schindlers and Galka Scheyer who was a major influence in her art career. She would shortly after this letter move to New York and room with Louise Nevelson who struck up an affair with Diego Rivera.).

de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, ca. 1930. Louis Christian Mulgart, architect, 1919-21.

Shortly after the de Young exhibition opened Weston hosted a "memorable" party in his Carmel studio of which he described,

"Sunday night (April 16) we held a party to be remembered, a rare gathering which brought together congenial persons who like to play, be gay; not one of them was a false note, each contributing to the fun, and spontaneously. Came: Fernando Felix, who plays the guitar and sings - Mexican songs of course - Nacho Bravo, who dances the rumba, - these two here with the newly-established Mexican consulate; Wilna Hervey and Nan Mason (see below), who played and sang in their delightful way; and then the group who have been gathering recently for dancing and vino, - Xenia, Francis, Elaine, Nan and Ed [Ricketts]; finally, there was Michael Schindler here for a few days. We had plenty of good vino, white and red, Fernando's singing was memorable, Xenia sang in Russian, Sonya in Spanish and Polish, I improvised, danced a Kreutzberg and a "Spring" number, also I danced with Wilna who is almost a foot taller than I am, and must weigh 350! It was a party without one dull moment, ending dramatically when, with a knock at the front door about 1:00, the night watchman complained of too much noise! His nearest "beat" is a block away." (DB, April 18, 1933, p. 273).

Seven Arts Building, Carmel, 1926. Herbert Heron, owner, Albert B. Coats, architect. Photographer unknown. Photo scanned from Carmel: A History in Architecture by Kent Seavey, Arcadia, 2007, p. 68. Courtesy of Pat Hathaway, California Views. Weston's studio was in the upper right dormer from1930-35.

Nan Mason and Wilna Hervey on an unidentified beach in winter. Photographer and date unknown. Courtesy Reiss Archives, Henriette Reiss Papers. www.winold-reiss.org.

Schindler was likely passing through town on his way back to Los Angeles after attending festivities related to his de Young show. It seems likely that Henry and/or Xenia were also in San Francisco for the opening since it must have been a heady experience for the young protege to be exhibiting among such illustrious company. If they were in San Francisco, they also possibly crossed paths with Schindler. Having a well-earned reputation as a notorious womanizer and partier like Weston, it is interesting to speculate upon the likelihood of Schindler taking advantage of Sonya's presence at this party and making a play for Xenia or vice versa for that matter. (For an example of Schindler's reputation see Conrad Buff: Artist, p. 123).

Jean Charlot, Mexico, 1927 by Henrietta Shore.

Zomah Day, Carmel, August 1933. Sonya Noskowiak photograph. From Weston & Charlot: Art & Friendship by Lew Andrews, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2011, plate 32. Courtesy Arthur F. Noskowiak. Jean Charlot Collection, University of Hawaii at Manoa Library.

An old friend of Weston's and Shore's from Mexico, Jean Charlot, and his girlfriend Zohmah Day (see above) paid Weston a lengthy visit later that summer shortly after he had returned from a trip to Taos, New Mexico with Sonya and Willard Van Dyke at Mabel Dodge Luhan's invitation. (For much more on this see my Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence). Weston, Charlot (see two above) and Shore all sat for portrait sessions of each other in Mexico and Carmel. Weston wrote of their arrival,

"The most important event of the summer was a visit from Jean Charlot who spent several weeks with us, bringing with him Zomah Day, a strange little sprite of whom we became quite fond. As to Jean, I found that we are as close together, in friendship and in work as before, though seven years had separated us since Mexican days." (DB, September 14, 1933, p. 275).

Weston was able to arrange exhibitions for Charlot at the Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel, the newly established Ansel Adams Gallery in San Francisco and Willard Van Dyke's 683 Brockhurst gallery in Oakland. Jean and Zomah arrived in Carmel the day of the Denny-Watrous opening. Charlot had come from Los Angeles where he had been making arrangements with noted book designer, impresario and Weston and Shore patron Merle Armitage to work with Lynton Kistler on the production of his Picture Book; 32 Original Lithographs. (See below) To help defray his living expenses while in Los Angeles he also arranged with Nelbert Chouinard to teach at her school that fall following in Siqueiros's Chouinard mural class footsteps from the year before. (See my Richard Neutra and the California Art Club for more on Siqueiros' controversial 1932 Los Angeles visitation).

"The Tortilla Maker" (Book cover for Jean Charlot, Picture Book; 32 Original Lithographs by Jean Charlot; inscriptions by Paul Claudel; translated into English by Elise Cavanna (New York: J. Becker, 1933).

Art critic and Weston and Schindler intimate Arthur Millier authored a lengthy feature on Charlot's career and reported that Charlot had unsuccessfully offered to do a mural for free in Los Angeles if a suitable wall and materials would be provided and that the New York Times called his Picture Book "An Art Show Between Covers." (Millier, Arthur, "Pink Teas Sidestepped by Hardworking Mural Artist; Man Who Painted First Modern Fresco in Mexico Got No Wall Here But Did Make Grand 'Picture Book'," Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1934, p. I-7).

Henrietta Shore, 1933 by Jean Charlot. From Weston & Charlot: Art & Friendship by Lew Andrews, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2011, plate 55.

Henrietta Shore, 1927. Portrait by Edward Weston. From Henrietta Shore: A Retrospective Exhibition: 1900-1963, edited by Jo Farb Hernandez, Monterey Peninsula Museum of Art, 1986, p. 21. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Merle Armitage, pencil drawing, ca. 1933. Portrait by Henrietta Shore. (From "Naturally Modern" by Victoria Dailey in LA's Early Moderns, Balcony Press, Los Angeles, 2003, p. 51).

Henrietta Shore by Merle Armitage, E. Weyhe, New York, 1933. (From Designed Books

by Merle Armitage, E. Weyhe, New York, 1933. (From Designed Books by Merle Armitage, E. Weyhe, New York, 1938, p. 116).

by Merle Armitage, E. Weyhe, New York, 1938, p. 116).

Edward Weston by Merle Armitage, E. Weyhe, New York, 1932. (From Designed Books

Fresh off of his success publishing the first ever book, Edward Weston (see above), Armitage also asked Charlot to transpose his 1929 portrait of Shore (see four above) into a lithograph that he wanted to use for the frontispiece for another upcoming book he was producing on Shore. (See two above). Merle also asked a somewhat reluctant Weston to write the introduction and photograph Henry's art work. (DB, December 8, 1933, p. 265). Jean asked Edward not to say anything about the portrait to Henry for fear she would not like his unflattering rendition. (See above). Charlot later recalled,

"I was asked to do it by Armitage - kind of a last minute job. She really looked like that. She didn't like it much. I met her first when she went to Mexico. She had asked permission to do my portrait and that of Orozco - so I reciprocated. I did an article on her. She was a very good painter." (Andrews, p. 112).

Jean Charlot, Carmel, August 1933. Photo by Sonya Noskowiak. From the Jean Charlot Collection, University of Hawaii.

After Jean and Zohmah had been in Carmel for close to two weeks, they accompanied Edward, Sonya Henry on an August 17th outing to Point Lobos. Henry got stuck on the side of a cliff and cried out for help. Jean had a near-fatal mishap going to her rescue while also damaging his glasses in the process (see above). The incident was later reported in the local newspaper:

"Jean Charlot, visiting Mexican painter, norrowly [sic] escaped death at Point Lobos one day last week when a rock gave way with him on the side of a steep cliff. He fell some distance down the side followed by a shower of rocks but fortunately escaped with minor cuts and bruises. Charlot was going to the help of Henrietta Shore, local artist, who had been lost for some hours and was unable to get back up the cliff to join the rest of the party which included Zoma [sic] Day and Sonya Noskowiak and Edward Weston. Miss Day brought help from the gate who helped Miss Shore and Charlot to safety. The party went to Point Lobos to work; Miss Noskowiak and Mr. Weston with cameras and Miss Shore and Mr. Charlot to sketch." ("Visiting Artist Has Narrow Escape in Fall," Carmel Sun, August 31, 1933).