See Part I at: Irving Gill, Homer Laughlin and the Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Los Angeles, Part I: 1893-1911

(Click on images to enlarge)

Miltimore House, South Pasadena, Irving Gill, architect, 1911. Gill, Irving, "The Home of the Future: The New Architecture of the West: Small Homes for a Great Country," The Craftsman, May 1916, p. 146. UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

In early September 1911, the Olmsteds resigned from their Exposition commission over an ongoing site-planning dispute with Goodhue and the Exposition's Director of Works, Frank Allen. ("Olmsted Quits in a Huff," Architect and Engineer, November 1911, p. 101). Out of sympathy with Olmsted, Gill's patron and client George Marston also resigned his position as chair of the Exposition’s Buildings and Grounds Committee. By then, Gill must have realized that he had been passed over for a position of any significance, despite being well-connected to some of the Board members, especially Marston. This, coupled with his differences in design philosophy with Goodhue, led him to sever all ties with the Exposition by the fall of 1911. (Author's note: For the most detailed analysis of Gill's brief involvement with the Exposition, see Amero, Richard, "The Question of Irving Gill's Role in the Design of the Administration Building in Balboa Park," San Diego History Center.)

Marion Olmsted, date and photographer unknown. From the National Park Service.

Fascinatingly, sometime in March of 1911, Gill was commissioned to design a cottage for the Olmsted brothers' sister Marion for a piece of property she owned at the southeast corner of Randolph and Stockton (now Arbor Dr.) Streets in San Diego's Mission Hills neighborhood. It has not yet been determined how this commission came about. Perhaps she had met Gill in 1900-01 while he was overseeing the construction of her Uncle Albert's mansion "Wildacre" in Newport, Rhode Island, and/or at one of the numerous social events surrounding the planning for the Exposition during the winter of 1910-11. She also may have been introduced to Gill by fellow artist Alice Klauber at a local art opening. In any event, the house was never built, and the land became the site of the Francis W. Parker School, which was founded in 1912.

Gill likely watched with much interest as yet another Harrison Albright reinforced concrete mega-project took shape in 1908-9 for automobile parts mogul Henry H. Timken, Sr., inventor and patent holder of the tapered roller bearing and many other parts used in the burgeoning automobile industry (see above and below). Ironically, the same week Gill's Laughlin House bids were being received in the Laughlin Building, Albright was also receiving bids in his Laughlin Building office for the 8-story office building at the corner of 6th and E Streets in San Diego for Timken. ("Eight-Story Building to Cost $250,000," LAH, April 12, 1908, p. 8)).

While the Timken Building was under construction, Timken's wife, Fredericka (see above) passed away in late 1908, followed by Timken himself in early 1909. ("Millionaire Carriage Manufacturer Expires," LAH, March 17, 1909, p. II-2). Frequent San Diego winter visitors, the Timkens, led by Henry Timken, Jr., traveled from the Midwest to settle their father's affairs. Henry, Jr. met Albright and, through him, almost certainly Laughlin and Gill. This ultimately resulted in Timken, Jr. commissioning Gill to design a grand residence at 335 Walnut Ave. around the corner from his father's estate at 3430 4th St. in May or June 1911 (see below). ("Contracts Awarded: San Diego [Timken House]," SWCM, July 1, 1911, p. 11).

Timken family portrait, ca. early 1900s. Photographer unknown. Seated in front, Henry, Sr., and Fredericka, with their five children. Henry, Jr., back row, second from left. From Timken by Bettye H. Pruitt, Harvard Business School Press, 1998, p. 17.

While the Timken Building was under construction, Timken's wife, Fredericka (see above) passed away in late 1908, followed by Timken himself in early 1909. ("Millionaire Carriage Manufacturer Expires," LAH, March 17, 1909, p. II-2). Frequent San Diego winter visitors, the Timkens, led by Henry Timken, Jr., traveled from the Midwest to settle their father's affairs. Henry, Jr. met Albright and, through him, almost certainly Laughlin and Gill. This ultimately resulted in Timken, Jr. commissioning Gill to design a grand residence at 335 Walnut Ave. around the corner from his father's estate at 3430 4th St. in May or June 1911 (see below). ("Contracts Awarded: San Diego [Timken House]," SWCM, July 1, 1911, p. 11).

Henry Timken, Jr. Residence, 335 Walnut Ave., San Diego, Irving Gill, architect, 1911. From Roorbach, Eloise, "Outdoor" Life In California Houses, As Expressed in the New Architecture of Irving Gill," The Craftsman, July 1913, pp. 435-38.

Gill traveled to Chicago via Los Angeles, Seattle, and Minneapolis in June 1911, possibly to go over the plans with Timken. He continued on to New York and his hometown of Syracuse, perhaps for the graduation from the Syracuse University School of Architecture of his nephew Louis, whom he invited to join his office in San Diego later that year. Contracts were signed, and a building permit was issued for the Timken House in early July. (op. cit.). This Gill-Albright-Timken connection would likely have paid dividends to Homer Laughlin, Jr. when he began his automobile production company a few years later (see discussion later below). (Various correspondence in the Panama-California Exposition Digital Archive, Olmsted Papers. "Sunbeams: New Timken Residence on 4th Street between Upas and Walnut," San Diego Union, September 14, 1911).

"Huge Fee for Laying Out Industrial City" LAT, December 23, 1911, p. II-1).

While his brother John and associate partner James Dawson were still engaged with the San Diego Exposition, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. was contacted in Brookline, MA by George A. Damon, pioneering Pasadena city planner and recently appointed Dean at Cal Tech, on behalf of Jared Torrance's Dominguez Land Company. (Letter from Damon to Frederick Olmsted, Jr., June 14, 1911, Torrance Historical Society Olmsted Papers). Electrical engineer Damon had collaborated with Olmsted on the preparation of a report, "Pittsburgh Main Thoroughfares and the Downtown District," in 1910. Damon was inquiring regarding Olmsted's availability for a trip to Los Angeles to discuss plans for what would become the new Industrial City of Torrance. In late 1911, it was announced that Olmsted had signed a $10,000 contract with the Dominguez Land Company to prepare the site planning and infrastructure specifications for the Torrance project. His preliminary plan was completed by the end of the year. (Ibid and "Modern City Takes Shape," LAT, December 27, 1911, p. II-6).

"Riverside Portland Cement Co.'s Enlarged Plant" and Olmsted, Frederick Law, "City Planning, Street Platting, Transportation, Building Codes and Grouping," SWCM, January 20, 1912, pp. 10-12.

On January 6, 1912, Olmsted spoke on "City Planning: Street Platting, Transportation, Building Codes and Grouping" at the Los Angeles City Club, with Damon and Gill likely in attendance. The talk was excerpted in the January 20th issue of Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer (see above). Coincidentally, across the fold in the same issue Gill likely read with great interest was a feature story on the Riverside Portland Cement Plant, where he would be commissioned to design workers' barracks only a few months later (see discussion later below). (Ibid). The article and accompanying ad (see below) highlighted the major projects in Los Angeles and San Diego that the company supplied cement for, many of which were designed by Albright.

"A Record in Cement," SWCM, January 20, 1912, p. 27.

Jared Torrance, ca. 1906, photographer unknown.

LAT, July 21, 1912, p. II-9.

Through the largess of Olmsted, who possibly felt some residual pangs of guilt and regret over his aggressive lobbying for Goodhue in San Diego, Gill was one of five architects, including Richard Farquhar, Elmer Grey, Sumner Hunt, and Parker O. Wright, selected by Olmsted in early 1912 to submit schemes for the general layout for the new city (see above). Tilt-slab construction patent holder Thomas Fellows also lobbied Olmsted strongly for the position. ("Experts to Make Plans for New Industrial City," LAH, February 5, 1912, p. 9. For more on Fellows and his lobbying of Olmsted for the position, see my "Irving Gill's First Aiken System Project" (Gill-Aiken).

Henry H. Sinclair at the helm of "Lurline." "Contenders In Transpacific Yacht Race, Commanders and Cup," LAH, July 4, 1908, p. 1.

Gill was finally chosen in April by Jared Torrance's Dominguez Land Company General Manager and former vice-president of the Edison Company, H. H. Sinclair (see above), to head the company's architectural department. The well-connected Sinclair also had close ties to J. D. Spreckels, having purchased his yacht "Lurline" in 1903. (Author's note: Spreckels had first "discovered" San Diego while sailing the Lurline into San Diego Bay in 1887 on a pleasure cruise.) (San Francisco: Its Builders Past and Present, Chicago, 1913, Vol. I, pp. 12-17. Cited in Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan and the Skyscraper by Donald Hoffmann, Dover, 1998, p. 88, n. 4).

Sinclair had also hired Ralph Bennett as Chief Engineer to design and construct the public works infrastructure needed to fulfill Olmsted's plan. Gill would have especially relished being chosen over Elmer Grey if he were aware of the role he played in Goodhue's selection over him for the San Diego Exposition. (For example, Letter from Elmer Grey to Bertram Goodhue, January 4, 1911). (Author's note: Like Sinclair, Jared Torrance was also a former vice-president of Edison Electric, which later merged to become part of Southern California Edison. Gill's 1910 client, Frederick Lewis, also later became a Southern California Edison vice-president. Coincidentally, by then having become Edison's Los Angeles District Superintendent, Lewis was most likely involved in providing power to the new city of Torrance from Edison's Long Beach Steam Plant. ("Electricity a City Builder," Torrance Herald, February 20, 1914, p. 1). Torrance was also a major benefactor of Charles Lummis's Southwest Museum under construction at the same time the City of Torrance broke ground. Joining Torrance on the museum's board of trustees were Gill clients Homer Laughlin, Jr., and Bishop Johnson. Lummis's Landmarks Club had earlier commissioned Hebbard and Gill to perform emergency restoration work on the San Diego Mission.)

After Gill gave Sinclair and Bennett a tour of his work, most likely the Laughlin and Miltimore Houses, and the more apropos for the workingmen of Torrance, his Lewis Court project, Sinclair wrote to Olmsted of his selection of Gill.

"After careful study of the architectural work to be done at Torrance we yesterday appointed Mr. Irving J. Gill, of San Diego, our Consulting and Supervising Architect, which appointment I feel sure will meet with your hearty approval, as I recollect your strong endorsement of his work. I have, in company with Mr. Bennett, personally visited many of the houses built by Mr. Gill and have become quite enthusiastic about his type of construction, especially the interior work. Mr. Gill will give practically his entire time to the work and at a very moderate compensation. He will have an office with us and make his office in Los Angeles. I have advised the other architects, who furnished us sketches in competition, of this appointment and made payment to them in the amount agreed upon. In addition I have written Mr. Farquhar a personal letter explaining more fully than to the others." (Henry H. Sinclair to Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., April 16, 1912. Olmsted Papers, Torrance Historical Society).

By this time, Gill had already designed a railroad depot for the Pacific Electric Railway Company (see above and below). The Los Angeles Times reported,

"Under the arrangement just perfected [Gill] will have full charge of the architectural work on all the buildings to be erected by the Land Company of Torrance. Mr. Gill has established offices in the Title Insurance Building at Fifth and Spring Streets. At present he is preparing plans for the new railroad station to be erected at Torrance. Among other buildings that are to be built as soon as plans are out are a city building, a hotel, administration building, stores, rooming-houses, and about 100 cottages. The land company is considering the erection of only fireproof buildings, but this plan has not as yet been definitely settled upon." ("Select Architect," LAT, April 28, 1912, p. V-1 and "Building: Station," SWCM, April 13, 1912, pp. 16-17).

Pacific Electric Railway Depot, Torrance, 1912. Irving Gill, architect. From "Torrance, The Modern Industrial City: Being the Tale of To-Day and To-Morrow," West Coast, January 1913, p. 48.

While Gill was negotiating his Dominguez Land Company contract with Sinclair, which would keep him busily employed for the next year, Homer Laughlin also commissioned him to prepare landscaping and preliminary site plans for the subdivision of Laughlin Park (see discussion later below). Gill was assisted in the task by fledgling landscape architect Lloyd Wright, who was by then in his employ.

Shortly after the Olmsteds' September resignation from the Exposition over the site layout dispute with Goodhue, Lloyd excitedly wrote to his father of leaving his Exposition "gardening" job to throw in his lot with his old Adler and Sullivan stablemate, Irving Gill. He thought he had little chance for advancement at the Exposition with the Olmsteds no longer in the picture. Unbeknownst to Lloyd was the role his father played in Gill's leaving Adler and Sullivan for San Diego, as discussed early in Part I. Lloyd further reported to his Taliesin-preoccupied father on his and Woolley's visit with Gill and his subsequent job offer.

Not long after going to work for Gill, Lloyd was joined by his brother John in the Elk Apartments (see end of Part I). (My Father, p. 61). After a brief stint working for a paving contractor in Portland, Oregon, John made his way south to move in with older brother Lloyd as he was acclimating in Gill's office and perhaps working on the installation of the landscaping for the Timken House, then nearing completion (see above). By then, Gill's nephew Louis had also made his way to San Diego to go to work for his uncle and lived with him in his personal cottage at 3719 Albatross St. (see below). Lloyd brought his beloved cello to San Diego, John brought his violin, and Gill bought a piano for his nephew Louis, and the three played for hours at a time in Gill's cottage.

John aimlessly ran through a series of odd jobs, including hawking advertising posters designed by Lloyd. (My Father, p. 61). The nervy nineteen-year-old soon found employment with the Pacific Building Company as a draftsman, where he coincidentally worked on the plans for the Barney House across the street from Gill's house for George Marston (see below). (Seventh Avenue Historic Home Tour, Save Our Heritage Organization, 2010, pp. 18-19). (Author's note: Also working for the same company around this time was Gill's former field superintendent, Richard Requa. Gill's influence imbued the work of former employee and partner Frank Mead and his former field superintendent Richard Requa, who, along with new partner Frank Mead, who was briefly Gill's partner in 1907, designed a house next door in 1913 for Barney's son and daughter-in-law.)

After a modicum of success repetitiously drawing bungalow elevations, he decided to try his hand in a real architectural office. Possibly trading on his name, the then wannabe architect John quickly found menial office boy work with the busy Laughlin Annex architect Harrison Albright in late 1911 (see below). (My Father, p. 63).

Union Building, 2nd and Broadway, San Diego, Harrison Albright, architect. From the San Diego History Center.

Perhaps one of the Gill landscape projects Lloyd was alluding to in his September 1911 letter to his father was related to Laughlin Park, a planned subdivision of land Homer Laughlin, Sr. began accumulating in 1890 with an initial purchase from James Lick, founder of the Lick Observatory. His holdings eventually grew to 33 acres total and became known as Laughlin Hill, situated between Los Feliz Blvd. and Franklin Avenue in Hollywood (see below). Broadway Department Store owner Arthur Letts had purchased the adjacent 70 acres to the east in 1904.

Sometime in the 1890s, Laughlin, Sr., hired noted East Coast landscape architect Nathan F. Barrett to develop a landscape plan which, over 12 years, resulted in over 50,000 trees and shrubs being planted on the property. The hundreds of olive trees that were planted were likely obtained through the largess of the Miltimore Ranch in the San Fernando Valley. Laughlin had originally envisioned building a palatial family home on the site, but the death of his wife in 1909 altered the plan. In 1911, a still distraught Laughlin, Sr., sold his prized acreage to a syndicate headed by his son, who formed the Laughlin Park Company. Laughlin, Sr., passed away on January 13, 1913. (Author's note: A San Diego colleague of Gill's, San Diego horticulturalist Kate Sessions, came to Los Angeles to consult with Barrett during his 1902 Laughlin Hill site visit. "Bennial Notes," LAH, May 9, 1902, p. 9).

Out of respect for his father's labor of love, Laughlin directed that Gill's "Vistas" design take special care to minimize disruption to the existing landscape infrastructure created for his father by Barrett. Likely very educational for fledgling landscapist Lloyd, Laughlin also hired Knapp & Woodward, civil and landscape engineers, "to complete a botanical map ... drawn to scale, showing contour lines in every five feet of elevation. It shows the position of every tree and shrub, its size and botanical name." ("Unique Vistas at Laughlin Park," LAH, November 8, 1913, p. 14).

Coincidentally, Corbett had in 1910 completed a palatial home in Berkeley Square for real estate mogul C. Wesley Roberts, who had in July of 1912 become one of the financial backers for Gill's Concrete Building and Investment Company, discussed later below.

The well-connected Corbett would also design a house for the earlier-mentioned Gill client Frederick B. Lewis in 1914 (see "Lewis" in Part I). Lewis's rapid rise through the ranks at the Southern California Edison Company and steady income from his Gill-designed Lewis Court units in Sierra Madre enabled the construction of the 12-room, 2-story, $7,000 house at the then tony address of 1754 Camino Palmero in the heart of Hollywood (see upper left above).

In 1916, Dodd's Laughlin Park neighbor, C. F. Perry's widow Ada, sold her estate to Cecil B. De Mille for the then princely sum of $27,893. (Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille by Scott Eyman). Dodd quickly befriended De Mille and developed strong ties to well-heeled developers and the movie industry through his new neighbor and his Paramount Pictures partner Frank A. Garbutt, who was a fellow Los Angeles Athletic Club and Uplifters Club crony.

As previously mentioned in Part I, Garbutt was also a close friend of Homer Laughlin, Sr., through their Automobile Club connections. It was thus most likely through Laughlin and/or Dodd that Lloyd met Garbutt (and possibly De Mille) and was put in charge of Paramount's set design and drafting department for much of 1916-17. (Lloyd Wright, Architect by David Gebhard and Harriette Von Breton, Art Galleries, UC-Santa Barbara, 1971, p. 22). (For much more on the Dodd-Wright relationship, see my "SWMZW" and "Firenze Gardens, 5218-5230 Sunset Blvd., William J. Dodd, Architect, 1920"). For much on Garbutt see my "Playa del Rey: Speed Capital of the World, 1910-1913").

Lloyd Wright ca. 1910. From Lloyd Wright: The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr., produced and photographed by Allen Weintraub, Abrams, 1998, p. 232.

Lloyd Wright at Villino Belvedere, Italy, 1910. Photo by Taylor Woolley. From Fici, Fillipo, "Frank Lloyd Wright in Florence and Fiesole, 1909-1910," Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, Fall 2011, p. 11).

Lloyd first met Gill the previous August when he and his fellow Wasmuth Portfolio worker and European travel-mate Taylor Woolley proudly paid a visit to Gill's office with the likely intent of selling him a copy of the portfolio on which they had labored so hard. The previous May or June 1911, Lloyd's father had arranged with his periodic draftsman Woolley, who was then back at his home in Utah, a strategically planned West Coast sales trip. Wright armed Woolley with copies of the first volume of the portfolio and a prospectus of the same published by Ralph Fletcher Seymour (see below). (Alofsin, p. 92). (Author's note: Seymour would in 1912 also publish Wright's The Japanese Print. Seymour and his wife, Harriet, also during 1916-18, hosted former Smith College roommates Sophie Pauline Gibling and Marian Da Camara while Harriet and the girls were teaching at the progressive Ravinia School. This led to a lifelong friendship with the Schindlers. For more on the Schindlers-Seymours friendship, see my "Chats" and "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924")

Prospectus for Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (aka Wasmuth Portfolio), Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1911. (From Steinerag.com)

Before making his way to Southern California, Woolley had likely first visited the Pacific Northwest, where former fellow Wright apprentices Andrew Willatzen and Barry Byrne had formed a partnership after leaving Wright's Oak Park Studio and Walter Burley Griffin's Steinway Hall office a few years earlier. This is evidenced by Byrne and Willatzen seeking to buy the second volume of the portfolio upon its release around the end of 1911. (Alofsin, p. 308). (Author's note: As discussed later below, Woolley would go to work for Byrne between 1914 and early 1917 in Walter Burley Griffin's Monroe Building office after he left for Australia with wife Marion Mahony for the Canberra project.).

Irving Gill's San Diego Office between 1908 - 1917, 752 5th St. From Google Maps.

The impressionable architects' sales call at Gill's office (see above) undoubtedly resulted in a wonderful exposure to his post-partnership with Frank Mead's modernistic oeuvre, not to mention his take on the activities and politics then in play surrounding the Panama-California Exposition site planning. In late August, Wright summoned Woolley back to Chicago to help with the construction of Taliesin, his new home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, on which he began work about the same time Gill started on the Torrance project (see below). (Alofsin, p. 342, n. 52).

Taliesin, fall 1911. Photo by Taylor Woolley. Courtesy University State Historical Society, Taylor Woolley Photograph Collection..

"I therefore went to Architect Gill of this city. Woolley can tell you more of him than I can write. He is a good sound man with ideas and ideals. He is, to say the least, appreciative of your work. ... To the inspiration he gained at that time, he lays a great deal of his success. ... I had a talk with him, a fine talk. The upshot of it was that he would turn over all of his client's landscape work to me, give me a desk in his office, all the material and aids I needed with free reign to handle the matter as I saw fit. With the proviso always...that I receive my pay when I made the department pay. Don't laugh and say that I was a silly ass for taking it up for I am not. I know what lies in this particular job, I know what an opportunity is, and I seized it. I have been in the work head over heels for the last week. I have already had two propositions handed me to lay out and handle and more in view at 10%. ... but I don't get any 10% until the gardens are under construction or near completion which will be sometime next spring. ... I wouldn't let the opportunity slip [by] me without giving it a good six months tryout for anything in the world. It will mean the making of me if I can hang on." (Lloyd Wright to Frank Lloyd Wright, n.d., ca. early September 1911. Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence, Getty Research Institute and Alofsin, p. 342, n. 52).

Timken House, 4th and Walnut, San Diego, 1911. Irving Gill, architect. From Roorbach, Eloise, "Outdoor Life in California Houses," The Craftsman, July 1913, pp. 435-8.

Not long after going to work for Gill, Lloyd was joined by his brother John in the Elk Apartments (see end of Part I). (My Father, p. 61). After a brief stint working for a paving contractor in Portland, Oregon, John made his way south to move in with older brother Lloyd as he was acclimating in Gill's office and perhaps working on the installation of the landscaping for the Timken House, then nearing completion (see above). By then, Gill's nephew Louis had also made his way to San Diego to go to work for his uncle and lived with him in his personal cottage at 3719 Albatross St. (see below). Lloyd brought his beloved cello to San Diego, John brought his violin, and Gill bought a piano for his nephew Louis, and the three played for hours at a time in Gill's cottage.

Irving Gill Residence, 3719 Albatross St., San Diego, 1908. Photo by author, May 16, 2015.

John aimlessly ran through a series of odd jobs, including hawking advertising posters designed by Lloyd. (My Father, p. 61). The nervy nineteen-year-old soon found employment with the Pacific Building Company as a draftsman, where he coincidentally worked on the plans for the Barney House across the street from Gill's house for George Marston (see below). (Seventh Avenue Historic Home Tour, Save Our Heritage Organization, 2010, pp. 18-19). (Author's note: Also working for the same company around this time was Gill's former field superintendent, Richard Requa. Gill's influence imbued the work of former employee and partner Frank Mead and his former field superintendent Richard Requa, who, along with new partner Frank Mead, who was briefly Gill's partner in 1907, designed a house next door in 1913 for Barney's son and daughter-in-law.)

George and Anna Barney House, 3530 7th St., San Diego, Pacific Building Company. (Ibid)..

After a modicum of success repetitiously drawing bungalow elevations, he decided to try his hand in a real architectural office. Possibly trading on his name, the then wannabe architect John quickly found menial office boy work with the busy Laughlin Annex architect Harrison Albright in late 1911 (see below). (My Father, p. 63).

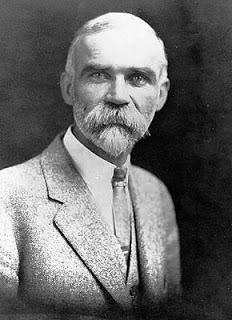

Harrison Albright, ca. 1912. Photographer unknown.

Albright had opened his San Diego office the year before in the recently completed Union Building he had designed for his best client, J. D. Spreckels, in 1907-08 (see above).

Various newspaper clippings ca. late December 1911. From Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright's Home of Love and Loss by Ron McCrea, Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2012, p. 122.

Shortly after going to work for Albright, the scandal surrounding his father's love affair with Mamah Borthwick and their new love nest, Taliesin, then under construction in Spring Green, Wisconsin, hit the front pages of newspapers across the country, including San Diego (see above for example). Likely the main motivation for John and Lloyd migrating to the West Coast was to distance themselves from the steady stream of gossip and negative press surrounding their father's affair. John was deeply concerned for his job upon seeing the headlines on Christmas Eve, 1911. He need not have been concerned, as the compassionate Albright immediately set him at ease. John recalled Albright from that point on, taking a keener interest and beginning more of a mentoring relationship with him. Over many weekends, Albright had John drive them in his Detroit Chalmers out to his Spring Valley ranch east of San Diego, which he had purchased in 1909. ("Architect Buys Fine Fruit Ranch," San Diego Union, November 25, 1909, p. 6, My Father, p. 61, and postcard below).

"The Harrison Albright Ranch," postcard from the internet.

I speculate that the Wright brothers moved into one of the two Gill cottages on what is now Robinson Mews (see below) sometime in mid-1912 evidenced by the fact that former Gill partner Frank Mead and draftsman Maury Diggs also lived at the same location in 1907 and 1908, respectively. The 1912 San Diego City Directory also still listed the boys as living at the Elk Apts. (San Diego City Directories for 1907, 1908, and 1912). (Author's note: Gill offered Diggs the rent-free use of the same cottage in 1913 during his headline news Mann Act trial.).

Gill Cottages, 3732-34 1st St. (now Robinson Mews), 1904. From San Diego History Center.

Perhaps one of the Gill landscape projects Lloyd was alluding to in his September 1911 letter to his father was related to Laughlin Park, a planned subdivision of land Homer Laughlin, Sr. began accumulating in 1890 with an initial purchase from James Lick, founder of the Lick Observatory. His holdings eventually grew to 33 acres total and became known as Laughlin Hill, situated between Los Feliz Blvd. and Franklin Avenue in Hollywood (see below). Broadway Department Store owner Arthur Letts had purchased the adjacent 70 acres to the east in 1904.

View from Laughlin Hill, 1905. From USC Digital Library.

Sometime in the 1890s, Laughlin, Sr., hired noted East Coast landscape architect Nathan F. Barrett to develop a landscape plan which, over 12 years, resulted in over 50,000 trees and shrubs being planted on the property. The hundreds of olive trees that were planted were likely obtained through the largess of the Miltimore Ranch in the San Fernando Valley. Laughlin had originally envisioned building a palatial family home on the site, but the death of his wife in 1909 altered the plan. In 1911, a still distraught Laughlin, Sr., sold his prized acreage to a syndicate headed by his son, who formed the Laughlin Park Company. Laughlin, Sr., passed away on January 13, 1913. (Author's note: A San Diego colleague of Gill's, San Diego horticulturalist Kate Sessions, came to Los Angeles to consult with Barrett during his 1902 Laughlin Hill site visit. "Bennial Notes," LAH, May 9, 1902, p. 9).

"Hollywood Beauty Spot a Landscape Masterpiece," LAH, September 13, 1913, p. 15. Rendering most likely by Lloyd Wright.

Las Casas Grandes, Laughlin Park, Hollywood, April 12, 1912. Irving Gill, architect. Drawing by Lloyd Wright. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Laughlin, Jr. had a grand vision for subdividing Laughlin Park and commissioned Gill to prepare landscape design and site plans, and presentation drawings to help market the property. Gill also authored a lengthy feature story for the Los Angeles Herald describing in detail the history of the property and the landscaping features he, with Lloyd's assistance, was designing to enhance the building sites in the development (see above and below).

Gill, Irving, "Unique Landscaping for Laughlin Park. Designed by Architect Irving Gill," LAH, August 23, 1913, p. 19.

Laughlin had selected an Italian villa theme for Laughlin Park residences and instructed Gill to implement a complementary landscape design for three "Cascade Vistas" which would enhance the marketability of the building sites (see above and below for example).

"The architecture probably will be largely what we are accustomed to call Italian, but only because Italian architecture has been developed along lines of fundamentals. In other words, Italian architecture—so called—has had a real reason for doing things, whether from a decorative or practical point of view." (Ibid).

Casas Grandes, Laughlin Park, Hollywood, 1912. Irving Gill, architect. (Rendering by Lloyd Wright?). Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection. I am deeply indebted to Curator Jocelyn Gibbs for sharing this image from Gill's scrapbook.

Out of respect for his father's labor of love, Laughlin directed that Gill's "Vistas" design take special care to minimize disruption to the existing landscape infrastructure created for his father by Barrett. Likely very educational for fledgling landscapist Lloyd, Laughlin also hired Knapp & Woodward, civil and landscape engineers, "to complete a botanical map ... drawn to scale, showing contour lines in every five feet of elevation. It shows the position of every tree and shrub, its size and botanical name." ("Unique Vistas at Laughlin Park," LAH, November 8, 1913, p. 14).

Las Casas Grandes, Laughlin Park, Hollywood, 1912. Irving Gill, architect. (Rendering by Lloyd Wright?). Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Development progress at Laughlin Park was well-publicized throughout most of 1913. For example, Gill's design philosophy for the residences was quoted in a December article in the Herald (see below).

“The houses to be built in Laughlin Park will be generally of plaster, fireproof construction, with red tile roofs, this red tile forming a natural and practical medium as it will give another primary color to the landscape, while the white of the houses will heighten the toning of the natural colors," said Irving J. Gill, who has charge of the landscape plans." ("Sewer Connection for Laughlin Park," LAH, December 13, 1913, p. 17).

"Mid Cypress and Hedges," LAT, August 10, 1913, p. VI-1. (Note C. F. Perry Residence at top of hill).

Laughlin Park development activity began in earnest in 1913 with C. F. Perry purchasing one of the 40 original home sites and commissioning architect B. Cooper Corbett to design his Italian villa (see above and below). ("Will Crown Hill; Laughlin Park Home to Follow Italian Villa Type; Grounds to be Elaborately Laid Out," LAT, March 9, 1913, p. VI-1). Perry was likely a close friend of the Laughlins and a fellow Automobile Club member, as his motoring exploits were also frequent fodder in the Los Angeles Times. (See, for example, "Auto Log Kept on Round Trip; Run to San Francisco and Back Interesting," LAT, December 27, 1908, p. VI-2).

C. F. Perry Residence, 4 Laughlin Park Dr., Laughlin Park, 1914. B. Cooper Corbett, architect. Purchased by Cecil B. De Mille in 1916. From Early Hollywood by Marc Wanamaker and Robert N. Nudelman, Acadia, 1907, p. 90. (Possibly the William J. Dodd Residence in the background was also purchased by De Mille in 1920.).

Coincidentally, Corbett had in 1910 completed a palatial home in Berkeley Square for real estate mogul C. Wesley Roberts, who had in July of 1912 become one of the financial backers for Gill's Concrete Building and Investment Company, discussed later below.

Frederick B. Lewis Residence, 1754 Camino Palmero, Hollywood, B. Cooper Corbett, architect. "Homes Display Individuality," LAT, December 27, 1914, p. VI-1.

The well-connected Corbett would also design a house for the earlier-mentioned Gill client Frederick B. Lewis in 1914 (see "Lewis" in Part I). Lewis's rapid rise through the ranks at the Southern California Edison Company and steady income from his Gill-designed Lewis Court units in Sierra Madre enabled the construction of the 12-room, 2-story, $7,000 house at the then tony address of 1754 Camino Palmero in the heart of Hollywood (see upper left above).

William J. Dodd, ca. 1910. From Wikipedia.

Intrigued by all the publicity surrounding the Laughlin Park development shortly after his early 1913 arrival in Los Angeles, architect William J. Dodd (see above) purchased from Homer Laughlin the lot next to Perry's commanding site at the top of the hill and began designing his personal residence. Fellow architect J. Martyn Haenke also bought a prominent lot, and perhaps through this connection, the two formed a partnership that would last for a couple of years. ("Architects Build at Laughlin Park," LAH, September 13, 1913, p. 15. Author's note: Dodd also joined the Los Angeles Athletic Club in 1913 and was one of the founding members of the LAAC-affiliated Uplifter's Club for whom he designed a clubhouse in 1921. For much more on the Dodd-Lloyd Wright relationship, see my "R. M. Schindler, Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Lawrence Tibbett, Reginald Pole, Beatrice Wood and Their Dramatic Circles"(SWMZW).

Getting his start in the Chicago office of William LeBaron Jenney six years before Lloyd's father began with Silsbee, Dodd moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he remained until moving to Los Angeles. Dodd was quite familiar with Wright, Sr.'s work as they had exhibited together in the Chicago Architectural Club's 13th annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1900. Around the time Dodd and Haenke were buying their lots and forming their brief partnership, Frank Lloyd Wright was back from Japan again, visiting his sons. Thus, it seems quite likely that Gill, Laughlin, Haenke, Dodd, and the Wrights would have discussed Laughlin's vision for Laughlin Park while socializing during the elder Wright's visit. Dodd, FLW, and Laughlin also had in common a pottery connection, as both Dodd and Wright designed Arts and Crafts vases for Teco Pottery in the early 1900s (see below).

Teco designs by William J. Dodd, Teco Catalog, 1905. From Wikipedia.

Teco Unity Temple design, ca. 1906, by Frank Lloyd Wright. From Wikipedia.

Dodd did not break ground on his residence until July 1914 and completed it in early 1915. Dodd had taken an immediate liking to Lloyd and put the rapidly blossoming designer to work on his estate landscape design after his mid-1914 return from Chicago discussed later below. Lloyd's rendering for the same was exhibited in the fifth annual exhibition of the Los Angeles Architectural Club in 1916 (see below). Dodd would continue to involve Lloyd on various other projects between 1914 and 1922. (SWMZW). ("Architects Build at Laughlin Park," LAH, September 13, 1913, p. 15. "Architect to Build," LAH, July 25, 1914, p. 16. "First of Fine Homes Finished," LAT, August 2, 1914, p. V-1. Author's note: Around the time Lloyd was likely installing the landscape for Dodd's home in Laughlin Park, he had also prepared landscaping plans for Dodd's Frank Upman House at 401 S. Westmoreland. LAH, December 24, 1914, p. 10).

Entrance to the Dodd Residence, 5 Laughlin Park Dr., Laughlin Park. Rendering likely by Lloyd Wright. From Grey, Elmer, "Fifth Annual Architecture Exhibit at Los Angeles," Architect and Engineer of California, March 1916, p. 47.

Haenke was completing work on a stately Windsor Square residence for real estate developer Dr. Edwin Janss around the time

William J. Dodd arrived in Los Angeles. In October, shortly after Dodd and Haenke purchased their Laughlin Park lots and formed their partnership, they also broke ground on a nearby Windsor Park mansion

for Edwin's brother, Dr. Peter Janss (see below). Through Dodd's largess, his eager protege Lloyd Wright was

commissioned by Peter Janss to landscape the grounds of his recently completed

estate.

Lloyd wrote his father after his early 1915 visit to

Southern California, discussed later below,

"Again I repeat that it is time to make our exhibition here. I will have a few local gardens of my own to show now. Dodd's, Upman's and Dr. Janss' and I have some ideas in regard to the introduction of plants that might prove valuable in the display of the two phases of the work." (Letter from Lloyd Wright, then in Los Angeles, to FLW, after his return to Taliesin, n.d. but likely ca. June, 1915. Copyright Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation 1990.).

Dr. Peter Janss Residence, 455 S. Lorraine Blvd., Windsor Square, J. Martyn Haenke and William J. Dodd, architects, 1913-14, Lloyd Wright, landscape architect, 1914. From Paradise Leased.

As previously mentioned in Part I, Garbutt was also a close friend of Homer Laughlin, Sr., through their Automobile Club connections. It was thus most likely through Laughlin and/or Dodd that Lloyd met Garbutt (and possibly De Mille) and was put in charge of Paramount's set design and drafting department for much of 1916-17. (Lloyd Wright, Architect by David Gebhard and Harriette Von Breton, Art Galleries, UC-Santa Barbara, 1971, p. 22). (For much more on the Dodd-Wright relationship, see my "SWMZW" and "Firenze Gardens, 5218-5230 Sunset Blvd., William J. Dodd, Architect, 1920"). For much on Garbutt see my "Playa del Rey: Speed Capital of the World, 1910-1913").

Cecil B. De Mille family in their Laughlin Park yard ca. 1920. Photographer unknown.

After leasing his house to Charlie Chaplin in 1918, Dodd would also sell his 5,600 sq. ft. home to De Mille in 1920. (Eyman). This enabled the larger-than-life mogul to join the two buildings to create a majestic compound at his egotistical new street address of 2000 De Mille Drive. De Mille, in turn, commissioned Dodd to remodel the compound for him in 1921 (see below). (For photos of Dodd's remodel for De Mille, see California Homes by California Architects by Ellen Leech, California Southland Magazine, Los Angeles, 1922, pp. 12-13).

De Mille and granddaughter Cecelia in the loggia designed by Dodd connecting the two houses. Photographer unknown, ca. 1940.

Landscape for Cecil B. De Mille Residence, 2000 De Mille Dr., Laughlin Park, ca. 1914-1921. William J. Dodd, architect, Lloyd Wright, landscape architect. (Leech, p. 13). (See also Lloyd Wright papers, 1920-1978, Box 628, UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library).

Dodd's renovations of his former house for De Mille included new offices, a library, a screening room and guest accommodations, and connecting the two houses with an elaborate loggia (see above and below). Dodd bought another nearby Laughlin Park lot and broke ground for his new 2-story, 10-room, $30,000 house at 2 Laughlin Park Dr. (now 5226 Linwood Dr.) in April 1921. Shortly thereafter, he began another mansion at 7 Laughlin Park Dr. (now 5235 Linwood Dr.) for real estate and automobile sales mogul Kenneth Preuss. Both Dodd and Preuss commissioned Lloyd to design their extensive landscape plans. ("[Preuss] Residence," SWBC, July 8, 1921, p.19. "Erecting Home of Unusual Design in Foothill Tract," LAT, December 18, 1921, p. V-1. Author's note: Lloyd would, in 1922, begin design and break ground on a house for Martha Taggart, the mother of his close friend Reginald Pole's wife Helen, a few blocks to the west of Laughlin Park. For much more on the love triangle of Lloyd Wright, Helen Taggart, and her first husband, Reginald Pole, see my "SWMZW." By 1923, architect Carleton Winslow had also designed his personal residence at 11 Laughlin Park Dr.)

De Mille Compound, 2000 De Mille Dr., Laughlin Park, ca. 1921. From Hollywoodphotographs.com.

Despite certainly having high hopes for commissions from clients wealthy enough to purchase lots in Laughlin Park, Gill's aspirations would go unrealized. Ironically, Lloyd would gain much more out of the Laughlin Park connection via his landscaping commissions from Dodd, set design work for Garbutt's and De Mille's Paramount Pictures, and the associated connections this provided to spur his budding career. (See, for example, my "Tina Modotti, Lloyd Wright and Otto Bollman Connections,1920").

Concurrent to the Laughlin Park landscape design work in the spring of 1912, Gill was selected to be the chief architect for Jared Torrance's Dominguez Land Company's new Industrial City of Torrance as described in his 1913 Press Reference Library bio below.

"In the early part of 1912 Mr. Gill was chosen by the Dominguez Land Company, a great California corporation, to design and supervise the construction of a model industrial city. This town, known as Torrance, lies near Los Angeles, California, and will be made up of factories of various description, administration buildings and all that goes to make an ideal manufacturing or industrial city, in one division, while another is set aside as the residence section and will be made up of the homes, schools, library, parks, children's playgrounds; the whole having paved streets and every modern facility, which will add to the convenience, beauty and sanitation of the place.

Mr. Gill has devoted himself to this work to the exclusion of practically everything else, although he conducts his offices in San Diego and holds commissions for many important structures in various parts of Southern California." ("Irving Gill," Press Reference Library, Notables of the West, Vol. I, International News Service, 1913, p. 571 (PRL)).

"Firm to Handle Vast Properties: Will be Selling Agents for Torrance," LAT, September 1, 1912, p. VI-5.

"Irving J. Gill, the architect in charge, is using concrete mission types in the construction and plans a white city for the residence and business portions of the 'tailor-made town.' ("Torrance "Tailor Made Town" Nearly Ready," LAH, August 31, 1912, p. 1).

Pacific Electric Railway Depot flanked by the El Roi Tan Hotel and Murray Hotels. Depot still exists in an altered state.

Irving Gill buildings, Torrance, from Bennett, Ralph, "The Industrial City of Torrance, California," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, October 30, 1913, p. 871.

Irving Gill buildings, Torrance, from Bennett, Ralph, "The Industrial City of Torrance, California," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, October 30, 1913, p. 871.

Torrance Elementary School, 1824 Cabrillo Ave., 1913. Still exists in an altered state. From Kamerling, p.

Ca. 1913 postcard depicting Irving Gill's Brighton and Colonial Hotel buildings on Cabrillo Avenue.

Gill's Brighton Hotel Building on the left above, at the northwest corner of Cravens and Cabrillo Avenues, still exists in an altered state. Continuing north, Gill's Colonial Hotel, located at the southwest corner of Gramercy and Cabrillo, also still exists in a similarly altered state. Off in the distance is Gill's El Roi Tan and/or Murray Hotel (both no longer existing), across Cabrillo from his still existing Pacific Electric Railway Depot, not visible on the right.

Hendrie Rubber Company Plant. From Kamerling, p. 93.

Besides the commercial buildings, hotels, and train depot in the new city's central core, Gill also designed two factory buildings in its eastern industrial district. The Hendrie Tire Factory and Fuller Shoe Factory both began operation in 1913 (see above and below).

From Bartlett, Dana W., "An Industrial Garden City," American City, October 1913, pp. 310-314.

(Ibid).

The above plot plan is intended for one of Torrance's new residential blocks, expanded upon Gill's Lewis Court project's use of communal space to improve the quality of life of the workers' families. Building the houses around the perimeter of the block freed up more communal area in the center for families to co-mingle and their children to play. City Beautiful Movement protagonist Dana Bartlett reported on Lloyd's landscape activity, "The fact that the company has planted 100,000 street trees, eucalyptus, acacia, pepper, and palm will assure the perfect forestation of the city." (Ibid).

(Ibid).

"Designs by Mr. Irving J. Gill," in Concrete Cottages edited by Albert Lakeman, Concrete Utilities Bureau, London, 1918, p. 145.

In a lengthy article in the Los Angeles Herald, as Torrance work reached a fever pitch, Gill discussed in great detail his earlier Lewis Court utopian design philosophy he was now adapting for his Torrance workingmen's cottages (see above and below). In the excerpt below, he explained,

"Suppose we are planning to build three or four houses in a row, each on its own lot. The old way was to build each without respect to the construction of the house next door. Under the new plan, the Torrance plan if you choose, each house ... is built, say, on the south property line, with its "blind" side to the south. Along this side of the house, in the front room, we will put our fireplace with stained glass, opaque window lights. This gives light into the house but does not permit any espionage by neighbors. Back of the living room, and still on the south side, let us place the bathroom. In that bathroom we will put a skylight, that can be opened to the light and air. What is the result of building a series of houses after this plan? Each house has its blind side, but each house also has an open side that is absolutely private. It Is toward this open side that the dining room and bedrooms are faced in order that they may be kept open and fresh without danger of intrusion on the part of inquisitive neighbors." ("Model Houses Being Built at City of Torrance; All Are of Concrete and Have Many Unusual Construction Features," LAH, July 12, 1912, p. 5).

"Designs by Mr. Irving J. Gill," in Concrete Cottages edited by Albert Lakeman, Concrete Utilities Bureau, London, 1918, p. 146.

In a visit to the new city by Jared Torrance's Pasadena cronies, Gill's concrete houses for workingmen "especially attracted their attention." ("Laud Torrance, City Industry," LAT, April 25, 1913, p. II-5). As discussed elsewhere herein, Gill had envisioned building hundreds of units employing his new Aiken System equipment. (Gill-Aiken). The designs were clearly ahead of their time and did not meet with the average buyer's approval; thus, the avant-garde simplicity of Gill's houses, coupled with a serious economic downturn in 1913-14, resulted in only about 20 of the units being built.

Aerial photo of Torrance, ca. 1920.

Gill turned selected Torrance landscaping projects over to Lloyd. The beautification of the city was described in detail in a December 21, 1913, Los Angeles Times article. ("Glimpses of Modern Industrial City of Torrance," LAT, December 21, 1913, pp. VI-2). Incorporating what he had learned from the Olmsteds in Boston, San Diego and Torrance and from Nathan Barrett's and Gill's Laughlin Park work, Lloyd eagerly involved himself with the design and planting of thousands of flowering shrubs and shade trees along the fledgling city's streets, a central park and eucalyptus tree wind breaks along the south and west ends of the city (see above). (See also "Torrance to Be one of the Most Beautiful Cities in the World," Torrance Herald, February 6, 1914, p. 1).

Southern Pacific Railroad Bridge, Torrance, Ralph Bennett, designer, 1914.

Like the entrance bridge to the Panama-California Exposition, the above iconic Southern Pacific Railroad bridge has been erroneously attributed to Gill. The bridge has even received landmark status, citing Gill as the architect. The errors can be attributed to Esther McCoy's pioneering writings on Gill in 1958 (Irving Gill, 1870-1936, Los Angeles County Museum exhibition catalog, p. 34) and 1960 (Five California Architects, p. 86). The Torrance bridge was designed by Torrance Chief Engineer Ralph Bennett in 1914. ("Concrete Bridge Begun at Torrance," LAH, May 16, 1914, p. 15. For more Gill mythology initiated by McCoy, see my "Gill-Aiken" and "Selected Publications of Esther McCoy, Patron Saint and Myth Maker for Southern California Architectural Historians").

"Spreckels Brothers Commercial Co., Agents: Riverside Portland Cement," SWCM, June 1, 1912.

"Spreckels Brothers Commercial Co., Agents: Riverside Portland Cement," SWCM, August 5, 1911, p. 37.

By 1911-12, Harrison Albright's client John D. Spreckels and his brother Adolph and their Spreckels Brothers Commercial Co. were acting as agents for the Riverside Portland Cement Co. (see above). This possibly provided the connection for Gill to obtain the commission for barracks for the company's workers around May or June of 1912.

Rendering for the Riverside Portland Cement workers barracks by Lloyd Wright, ca. July 1912.

This was an extremely busy time for Gill as the work at Torrance had, by mid-1912, ramped up to a peak. He was also frantically trying to incorporate and organize his Concrete Building and Investment Company. Evidenced by Lloyd Wright's above rendering for Gill's original design for the Riverside workers' barracks, he had envisioned using his newly purchased Aiken System equipment to construct side-by-side connected, flat-roofed, concrete compounds, the sides of which would form continuous rectangular walls, enclosing central communal gardens reminiscent of his Lewis Court project in Sierra Madre.

Riverside Portland Cement Worker's Barracks, Crestmore, 1912, Irving Gill, architect. Lloyd Wright, landscape architect. From Kamerling, p. 98.

Likely due to not being able to organize his equipment in a timely fashion and also the company seemingly wanting to reduce costs, Gill quickly redesigned the project to a more utilitarian pitched roof wooden compound with a shaded pavilion in the central garden, again along the lines of Lewis Court (see above and below). Gill's first Aiken System project would not come to fruition until early the following year. (Gill-Aiken).

Riverside Portland Cement Worker's Barracks, Garden Pavilion, Crestmore, 1912, Irving Gill, architect. Lloyd Wright, landscape architect. From Kamerling, p. 99.

In addition to the Torrance, Laughlin Park, and Riverside projects, Gill also put Lloyd to work on the landscape drawings for the Alice Lee and Katherine Teats houses at Albatross and Upas Streets, just three blocks directly south of his Robinson Mews cottages (see below).

Alice Lee Property Landscape Plan drawn by Lloyd Wright, landscape architect, July 1912. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Alice Lee Property Landscape Elevation drawn by Lloyd Wright, landscape architect, July 27, 1912. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Katherine Teats Cottage, Albatross, Irving Gill, architect, 1913. Rendering by Lloyd Wright. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Lloyd's rendering for the Teats cottage (see above) was clearly inspired by Marion Mahony's Wasmuth Portfolio rendering for FLW's 1905 Hardy Residence in Racine, Wisconsin (see below). (Author's note: Mahony's future husband, Walter Burley Griffi,n likely designed the landscape, the plans for which Lloyd would soon be studying after his brief return to Chicago with brother John in late 1913 and early 1914. Barry Byrne had also returned to Chicago in February 1914 to take over Walter Burley Griffin's practice and would have permitted Lloyd to study Griffin's projects. (Alofsin, Appendix A: Chronology, 19 September 1913 - Staff at Wright's Chicago Office: sons John and Lloyd, and Harry Robinson. Offices at 600-610 Orchestra Hall.)

Hardy House, Racine, Wisconsin, 1905. From Wasmuth Portfolio, Plate XV(c).

Katherine Teats Cottage and mature landscape, Albatross Street and Upas, Irving Gill, architect, Lloyd Wright, landscape architect, 1913. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Alice Lee and Katherine Teats Cottages, Albatross Street, Irving Gill, architect, 1913. Photo ca. 1913-14. From the San Diego History Center.

During this period, Lloyd also worked on the unbuilt O'Kelley project and produced the below rendering. (As cited in Lloyd Wright, Architect by David Gebhard and Hariette Von Breton, UC-Santa Barbara Art Galleries, 1971, p. 70).

O'Kelly House, 1st and Olive, San Diego, unbuilt, Irving Gill, architect, 1912. Rendering by Lloyd Wright, ca. 1912. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Collection.

Grace Fuller Residence, Glencoe, Illinois, 1906. From Plate XL, Wasmuth Portfolio, scanned from Frank Lloyd Wright: Drawings and Plans of Frank Lloyd Wright: The Early Period (1983-1909), Dover, 1983. Rendering attributed to Marion Mahony Griffin by H. Allen Brooks in his "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Wasmuth Drawings," Art Bulletin, June 1966, p. 202.

It was sometime in the spring of 1912 that Albright

entrusted the eager John with a residential commission for Mrs. M. J. Wood in

Escondido. Albright usually did not take on such menial commissions, but with

Mrs. Wood's permission, turned over the assignment to his eager

apprentice. (My Father, p. 66). For his inspiration, John used his

father's design for the Grace Fuller Residence in Glencoe, Illinois, which was

included in the Wasmuth Portfolio, certainly then in the brother's possession.

Lloyd also possibly assisted in producing he watercolor presentation drawing

for the project (see below).

Mrs. M. J. Wood House, 455 E. 5th St., Escondido, Harrison Albright, architect, John Lloyd Wright, designer, 1912. (Van Zanten, Ann, p. 45).

Exhilarated by every aspect of the experience of designing and building his first project, John committed to a career in architecture and began beseeching his father for an apprenticeship. On July 4, 1912, he wrote:

Writing again to his seemingly uninterested father on July 19th, he possibly piqued his interest with:Exhilarated by every aspect of the experience of designing and building his first project, John committed to a career in architecture and began beseeching his father for an apprenticeship. On July 4, 1912, he wrote:

"Now that I have charge of Harrison Albright's San Diego office - I will ask you, probably for the last time, for a position with you.

1st, Because you are my father.

2nd, I admire your architecture.

3rd, Because I am and will be able to help you." (Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan and the Skyscraper by Donald Hoffmann, Dover, 1998, p. 48).

"Mr. Albright has over a million dollars worth of work under construction in San Diego at the present time and his Theater Bldg., 6 stories high, covering nearly a square block, will be finished by the middle of month. His work is reinforced concrete and he takes nothing under $100,000. I am sending a few pictures of our little house. (Mr. Gill's work)." (Ibid).

Caroline Severance and Ella Giles Ruddy, ca. 1906.

Gill and Lloyd were extremely busy with the Torrance project through the rest of 1912 and early 1913. In November of 1912, Gill obtained another commission through his Laughlin-Albright pipeline, a house for feminist activist and socialite Ella Giles Ruddy (see above) and her husband George. Ruddy traveled in the same women's club circles as Homer Laughlin, Jr.'s wife, Ada, and lived right around the corner from Harrison Albright across the street from Sunset (now Lafayette) Park. (For much more on this Gill commission, see my "Ella Giles Ruddy House, 241 N. Western Ave., Irving Gill, Architect, 1913" (Ruddy)).

Bungalow Home of Mrs. George D. Ruddy, 241 N. Western Ave., Los Angeles. Irving J. Gill, Architect, 1913. (Ibid). (Author's note: I have not yet been able to determine whether the landscaping for this project was by Lloyd Wright.)

The Ruddys most likely met Gill through Homer and Ada Laughlin and/or through the Laughlin Bldg. Annex designer and tenant Harrison Albright. Ada was a fellow prominent clubwoman, and both of the Ruddys at times had offices in the Laughlin Building. George had a real estate brokerage office in the building, as did Ella while she was secretary of the Humane Animal League of Los Angeles. (Gill-Laughlin, Part I).

"The Studio-Home of Frank Lloyd Wright," Architectural Record, January 1913, pp. 45-54.

Before leaving with Mamah Borthwick for Tokyo to secure the Imperial Hotel commission in January 1913, Wright was able to place a 10-page spread of their love nest, Taliesin, in the Architectural Record, which would have been studied closely in architectural offices across the country. After missing the boat, the couple stopped over in Los Angeles to visit Lloyd and John. ("Personal Notes," SWCM, January 25, 1913, p. 10).

Gill and Albright would certainly have discussed Taliesin at great length with Lloyd and John. If the issue had hit the stands while their father was in town, they all would have discussed it together while getting a whirlwind tour of Gill's and Albright's work. The brothers would seemingly have had mixed feelings, great pride in their father's stunning masterpiece, which they would hear more about from him later that year, and a feeling of loss knowing that a reconciliation of their parents was now highly unlikely.

Left, Sarah B. Clark Residence, 7231 Hillside Ave., and right, Myra N. Brochon Residence, 7235 Hillside Ave., Hollywood, 1913. Irving Gill, architect. Landscape design likely by Lloyd Wright. "Pre-Cast Walls for the Concrete House," Keith's Magazine, October 1917, pp. 223-225.

The same month Wright and Borthwick left for Japan, Gill received commissions to design two adjacent residences on Hillside Dr. in Hollywood for Sarah B. Clark and Myra N. Brochon. The Clark Residence would be the first to be built with Gill's recently acquired Aiken System "tilt-slab" equipment. Ground was broken on both houses in February, and both were completed in late May by the time Wright returned from Japan. ("Gill-Aiken").

In the meantime, feeling snubbed by his father over his earlier apprenticeship request, the eager John appealed to one of Gill's European idols, Otto Wagner, for a spot in his Viennese atelier. This was about the same time his father's Wasmuth Portfolio was being discovered by Wagner, Adolf Loos, and their students and followers, including R. M. Schindler and Richard Neutra. (Alofsin, n. 142, p. 339).

John excitedly wrote:

"Mr. Otto Wagner, Architect

Vienna, Austria

Most Honorable Sir,

Your esteemed address I received from my father Frank Lloyd Wright, and allow me at this time to ask you if you have a position open in your highly respected house.

I am 21 years old, have a few years of practical experience in architecture and would gladly be prepared to send you drawing(s) or photographs, which will give you a sense of my abilities.

Respectfully yours,John fondly remembered Wagner's prompt reply "... come on..." Buoyed by Wagner's acceptance, he proudly sent his father photos of the Wood House and Workingmen's Hotel rendering and asked for help in buying a ticket to Vienna. Wright telegraphed back from Japan or San Francisco: "Meet me in Los Angeles in two weeks ... I'd like to know what Otto Wagner can do for you that your own father can't do!" (My Father, p. 67).

John Lloyd Wright

March 30, 1913" (Alofsin, n. 141, p. 339).

Francis Barry Byrne, ca. 1913, possibly in Los Angeles. From Alfonso

Iannelli: Modern by Design by David Jameson, Top Five Books, 2013, p. 98 (hereinafter Jameson)

During this exciting formative period in their lives, the Wright brothers were joined in February 1913 by their father's former Oak Park apprentice Barry Byrne (see above). Since leaving Wright's studio in 1908, Byrne had spent a year in fellow former Wright employee Walter Burley Griffin's Steinway Hall office. His next three years were spent in partnership with another fellow Wright apprentice, Andrew Willatzen, in Seattle, producing Wright-inspired Prairie Style residential architecture. Perhaps John had connected with the duo in the Pacific Northwest before joining Lloyd in San Diego in the fall of 1911.

Los Angeles Trust and Savings Building, 6th and Spring Sts., Parkinson and Bergstrom, 1911. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

By the time Byrne arrived in Southern California, the Wright Brothers and Gill were spending much more time in Los Angeles than in San Diego. Barry decided to try his luck in Los Angeles and opened an office in Room 807 of Parkinson and Bergstrom's Trust and Savings Building (see above). His office was next door to the architectural offices of the brothers Ross and Mott Montgomery, who quickly became fast friends with Byrne and the Wrights. (Author's note: Mott Montgomery would serve as Lloyd's best man during his November 1916 wedding to Kirah Markham. (SWMZW).

Jean Hotel, 840 S. Flower St. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Byrne found an apartment in the Jean Hotel 9see above) about a block away from Gill's soon-to-be 913 S. Figueroa office-residence (see below). (Los Angeles City Directory 1913). John and/or Lloyd possibly roomed with Byrne for much of their 1913 time in Los Angeles. The fun-loving trio began spending a lot of time at the nearby Orpheum Theater (see two below), where they were destined to meet young designer and graphic artist Alfonso Iannelli. Iannelli was commissioned to design the transom window over the Orpheum's main entrance at 633 S. Broadway (see three below).

Irving Gill Residence at 913 S. Figueroa St. (center left of church). Courtesy Los Angeles, Cal. : Birdseye View Pub. Co., [1909].

Orpheum Theater, 633 S. Broadway, G. Albert Landsburgh, architect, Carl Leonardt, contractor, 1911. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Main entrance transom window, Alfonso Iannelli, 1912. Jameson, p. 14. Also included in Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club: Fourth Exhibition, 1913.

Construction progress was closely followed by the local

press during 1911. Theater manager Clarence Drown (see above) carefully

orchestrated the Orpheum's move from its old location at 227 S. Spring St. into

its magnificent new building. ("Drown Genius of New

Orpheum," LAT, June 11, 1911, p. III-1). The old building then

became the site of the Lyceum Theatre (see below), also under Drown's

management. Drown was also one of the founding members of the Gamut Club, of

which Gill, around this time, also became a member. ("Where Melody

Abounds," Pacific Outlook, October 27, 1906, pp. 13-16). PRL,

p. 571.

Lyceum Theater Building (formerly the Los Angeles Theater and the Orpheum), 227 S. Spring St., F. J. Capitain and J. Lee Burton, architects, 1888. Interior remodeled by John Parkinson, 1903.

Alfonso and Margaret Iannelli, Chicago, 1916. Wikipedia via Chicago Daily News - Chicago Daily News negatives

collection, DN-0003451. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Coincidentally and possibly through Drown's largess, Iannelli moved his studio from 257 S. Broadway into the Lyceum Building sometime in 1912, shortly before he met Byrne and the Wrights (see above and below). Iannelli was then living at 715 S. Hope St., about a block away from Byrne's apartment and two blocks from Gill. (1913 Los Angeles City Directory).

Iannelli Studios business card, Jameson, p. 50.

Orpheum Theater lobby with Iannelli posters on display, 1912. Jameson, p. 12.

The Wrights and Byrne were immediately drawn to the modernist posters of Vaudeville performers. Drown commissioned Iannelli to design for the Orpheum lobby showcases (see above and below). John and Lloyd would soon introduce their Oak Park Studio friend Barry and new friend Iannelli to Gill, who would also happily mentor the new additions to this auspicious group of rapidly blooming designers.

Sarah Bernhardt, Orpheum Theater, March 1913. Jameson, p. 17.

Hamburger Department Store, 8th and Broadway, 1909. Alfred F. Rosenheim, architect. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

The same month Byrne arrived in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Architectural Club was holding its annual exhibition on the fourth floor of the Hamburger Department Store Building at 8th and Broadway (see above). The then-largest department store west of the Mississippi was designed by Alfred F. Rosenheim, who was also past president of the Los Angeles Architectural Club, the Fine Arts League of Los Angeles, and the Architectural League of the Pacific Coast. The prize-winning poster for the exhibition was designed by Iannelli's partner, James Frederick Rudy (see above).

Exhibition Poster designed by James Frederick Rudy, Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club: Fourth Exhibition, 1913.

James Frederick Rudy, Iannelli's first partner, in the Iannelli Studios at 221 1/2 S. Spring St., Jameson, p. 50.

A selection of Iannelli's sculpture and Orpheum posters were on display, some of which were also included in the exhibition catalog (see above and below). Iannelli's early sculpture was inspired by Rodin's work as taught by his now legendary teacher at the Art Students' League in New York, Gutzon Borglum. One of the above maquettes, "Spring," was awarded the Saint-Gaudens prize for sculpture in the 1908 Art Students' League show. (Jameson, p. 10). An active member and previous exhibitor, Gill also had work exhibited, as did Albright, Hebbard, and Byrne's and Lloyd's soon-to-be friends, the Montgomery brothers. Gill would certainly have attended the exhibition, possibly accompanied by his new group of followers.

"A Fountain by Iannelli," Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club: Fourth Exhibition, 1913.

Young John may have seen something in the show that sparked inspiration for the new project J. D. Spreckels had just commissioned Albright to begin work on, i.e., his Workingmen's Hotel in downtown San Diego (see below). Parkinson and Bergstrom's rendering for a commercial building in Los Angeles bears a striking resemblance (see below) to the project Albright entrusted John to begin work on about this time.

Commercial Building, Spring Street, Parkinson and Bergstrom, architects. Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club: Fourth Exhibition, 1913.

El Roi Tan and Murray Hotels flanking the Pacific Electric Railway Depot, February 9, 1913. Irving Gill, architect. Courtesy of Torrance, Torrance Historical Society.

John was also likely aided in this effort by his brother Lloyd's access to Gill's plans for the concrete hotel buildings (see above) recently completed for the industrial City of Torrance, which he would have also closely observed during trips to Los Angeles with Lloyd. The rendering below, which appeared in the June 21st issue of SWCM, includes at the upper corners sculptural elements designed by Iannelli. (See also Jameson, p. 58).

Workingmen's Hotel, 720 4th Ave., San Diego, 1913. Harrison Albright, architect; John Lloyd Wright, designer. "The Proposed Workingmen's Hotel in San Diego," SWCM, June 21, 1913, pp. 8-9).

Iannelli and John were by then close friends and familiar enough with each other's work to enable this artistic and architectural collaboration. John had to have also convinced Albright of Iannelli's talent if his boss had not seen his work on display at the February Architectural Club exhibition. Iannelli's recollection was that he first met John Wright when he called on Albright to inquire about a possible commission for some sculptural work for the Spreckels Organ Pavilion at the Panama California Exposition (see below). (Jameson, p. 51. For the best version of the Wright-Byrne-Iannelli meeting, see Barry Byrne, John Lloyd Wright: Architecture and Design by Sally Kitt Chappell and Ann Van Zanten, Chicago Historical Society, 1982, pp. 11, 43-44. For much more on Iannelli, see my "100 Years Ago Today: Robert Henri, Alice Klauber and Irving Gill Connections, April 25, 1915".

Spreckels Organ Pavilion, Balboa Park, 1914. Harrison Albright, architect, sculptural elements by Alfonso Iannelli.

John D. Spreckels, ca. 1912-13. Photographer unknown. From San Francisco: Its Builders Past and Present, Chicago, 1913.

Spreckels liked Iannelli's work enough to commission a bust, which he worked on while Spreckels was in Los Angeles conferring with Albright on their numerous projects. During the sessions,

"Mr. Albright and Mr. Spreckels would be discussing the new projects on which they were working, and also as to whether they would be a successful venture and their guide was the timing of these new buildings to the astrological positions of the stars. The constellation Leo seemed to be a good time to start, and the work would probably be finished the next year at the time of Virgo. I listened in amazement that these two grown up men could discuss such projects and such large expenditures of money and having astrology guide their moves." (Jameson, pp. 51-52).Byrne also received his first and only known Los Angeles commission around the same time John began work on the Spreckels' Workingmen's Hotel. Presaging his numerous future projects for the Catholic Church, the project was for the design of a three-building compound for the Church-affiliated Brownson House Settlement Association on Church property between Pleasant and Pennsylvania Avenues near Brooklyn Ave. in Boyle Heights. It is not hard to imagine Byrne drawing inspiration from John and Lloyd's copy of the Wasmuth Portfolio for his Prairie-Style compound (see below)..

"Noble Philanthropy Now Taking Shape, LAT, May 18, 1913, p. VI-4.

The site had been recently acquired for the settlement house compound by Bishop Conaty, whom fellow Irishman Byrne would likely have met. A period article described the compound:

"Francis Barry Byrne, 807 Trust & Savings Bldg., is preparing plans for a group of three social settlement buildings to be erected on Pleasant Ave., near Brooklyn Ave., for the Brownson House Association. The main building will be l-story with high basement and will contain a chapel, an auditorium seating about 300, club rooms, bowling alley and shower baths. Dimensions 35x15 ft. There will be a 2-story residence for settlement workers containing twelve rooms and bathroom; dimensions 38x60 ft. The priest's residence will be 1-story and will contain six rooms and bath. The building will be frame construction with exterior plastered on metal lath, shingle roofs, pine trim, hardwood and pine floors, furnace heat in each building, automatic water heaters, electric wiring. Contractors to bid on work selected." ("Social Settlement Buildings," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, May 17, 1913, p. 14. For more on this see my "Brownson House Settlement Association Compound, BoyleHeights, Francis Barry Byrne, Architect, 1913").After sailing back to San Francisco from Japan with the commission for the Imperial Hotel in hand in May-June of 1913, Wright and Borthwick again made a side trip to Los Angeles and San Diego to visit John and Lloyd and discuss their possible apprenticeships back in Chicago. ("Hotel News," San Francisco Call, June 8, 1913, p. 34).

The boys reconnected their father with the then very busy Gill, introduced him to Albright, and proudly gave him in-depth tours of their projects in Los Angeles and San Diego. They also seemingly would have visited Byrne's office and been shown his plans for the Brownson commission. Wright and Borthwick might also have been taken to see a performance or two at the boys' new hangout, the Orpheum Theater, where Iannelli's client Clarence Drown was the manager, and/or the Gamut Club, where he was one of the founders, and Gill had recently become a member.

Sherman Flats, Lemoyne St. and Park Ave., Echo Park, 1913, Irving Gill, architect. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Citizen's National Bank Building, southwest corner of Third and Main Sts., 1906, Harrison Albright, architect. Photographer unknown, ca. 1913. Courtesy California Historical Society, USC Digital Collection.

They also seemingly would have visited Gill's Concrete Building and Investment Company office in the Harrison Albright-designed Citizen's National Bank Building (see above and below) where he was then involved with his first Aiken System projects, the recently completed Clark House, the then under construction Powers Flats and the Mary Banning House, yet another prestigious commission received via the largess of the Laughlins. (Gill-Aiken).

Concrete Building and Investment Co. ad, LAH, September 21, 1912.

It seems plausible that Homer Laughlin, Gill, and Albright would have arranged some social events for Wright and Mamah, including selected Gill clients such as the Bannings, Miltimores, and especially the Ruddys. For example, the progressive club woman and feminist Ella Giles Ruddy was also president of the Los Angeles Wisconsin Badgers Club, the Equal Suffrage League, and vice-president of the Los Angeles LaFollette for President Club. She was also a frequent contributor to LaFollette's Magazine. ("LaFollette Friends Organize Club Here," LAH, March 2, 1912, p. 1 and Ruddy. Author's note: Coincidentally, Robert LaFollette's three children attended the Hillside School in Spring Green with Lloyd and John Wright.)

Ruddy and fellow women's activist Mamah Borthwick and Wright would have had much in common to discuss over dinner. University of Wisconsin graduate and prominent suffragette Ruddy published numerous articles on Scandinavia and Ibsen during her time in Chicago. It is also seemingly a certainty that she would have absorbed Borthwick's translations of the work of Swedish feminist and fellow suffragette Ellen Key while in Europe, while Wright was working on the Wasmuth Portfolio with Taylor Woolley and Lloyd.

Love and Ethics by Ellen Key, translated by Mamah Bouton Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright, Ralph Fletcher Seymour, Chicago, 1912.

Wright prevailed upon his Fine Arts Building publisher friend Ralph Fletcher Seymour to publish Borthwick's translations of Keys' The Morality of Women, Love and Ethics, and The Torpedo Under the Ark: Ibsen and Women after their return from Europe in 1911 (see above for example). There were numerous reviews of and lectures on Key's work advertised in the Los Angeles press in 1911-12, which Ruddy would have been privy to and likely attended. Perhaps Ruddy had even discussed with Lloyd and/or Gill while he was designing and completing her house, the relationship between Wright and Borthwick just before they arrived in Los Angeles. (For more on the Schindlers-Seymours friendship, see my "Chats" and "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924". Also, Langmead, no. 91).

Besides a tour of Gill's and Albright's work in San Diego, Wright and Mamah might have been introduced to like-minded clients such as Alice Klauber, George Marston, Ellen Scripps, and J. D. Spreckels. Besides viewing Albright's downtown buildings for Spreckels and Gill's impressive La Jolla work, they were likely taken to Balboa Park to view the construction status of the Panama California Exposition and may have visited Albright's ranch. Louis Gill recollected Wright's remark during his visit to the San Diego office and observing a beehive of activity underway with Gill's secretary, six draftsmen, and field superintendent, "Well, this looks like an architect's office." (Hines, p. 163 and note 9, p. 269).

San Francisco Call Building rendering, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1913. (Museum of Modern Art).