(Click on images to enlarge)

A. Lawrence Kocher, date and photographer unknown.

Perhaps the best known of the 12 children of long-time San Jose, California jewelry store proprietor Rudolph R. Kocher was son Alfred Lawrence Kocher, born in 1885, who became managing editor of the prestigious architectural journal Architectural Record between 1927 and 1938. Two of Rudolph's other sons, Jacob John Kocher, born in 1876, and Rudolph Alfred Kocher, born in 1883, became prominent doctors who made names for themselves in Palm Springs and Carmel, California, respectively, as will be discussed later below. (Family Search).

Kocher was born in 1885 as the second youngest of twelve children of Rudolph R. and Anna Kocher. Kocher graduated from Stanford University in 1909 and studied architecture at MIT until 1912. He then enrolled at Penn State University as a graduate student in

Architectural History and Design. Kocher opted to study eighteenth-century colonial architecture in Pennsylvania, for which he was ultimately awarded his master's degree in 1916. His Master's Thesis was titled "The Character and Development of Colonial Architecture in Centre County, Pennsylvania." ("Making Prefabrication American: The Work of A. Lawrence Kocher" by Anna Goodman, Journal of Architectural Education, Volume 71, 2017, Issue 1, pp.22-33; Centre County Historical Society ).

"Early Architecture of Pennsylvania" by A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, Vol. 48: pp. 513-530; 49: 31-43, 135-155, 233-248, 409-422, 519-535; 50: 27-44,147-157, 214-226, 397-406; 51: 507-520.).

Kocher's graduate research was essentially published in Architectural Record between 1920 and 1922 in a twelve-part series entitled "Early Architecture of Pennsylvania."(See above for example). Publication of these articles by Managing Editor Michael A. Mikkelsen proved quite important to the rise in Kocher's editorial career, as will be seen later below. While in the midst of publishing his research in the Record, Kocher was also busy designing and building three residences in State College, including his own. (See below).

Kocher House, 357. E. Prospect Ave., State College, PA, 1922. From "An American Style: Three State College Houses by A. Lawrence Kocher" posted in Hearts in the Highlands. Kocher was appointed to a full professorship at Penn State in 1918 and served as head of the Department of

Architecture until he left the University in 1924 to pursue doctoral studies in colonial architecture in Pennsylvania under Fiske Kimball at New York University. Regularly published in Architectural Record, Kimball had just arrived at NYU from heading, since it was formed in 1919, the University of Virginia Department of Art and Architecture, where he was succeeded by Joseph Hudnut in 1923.

After completing all of the class work for his doctorate in preservation, Kocher would forego completing his dissertation to instead succeed Joseph Hudnut as Director of the

McIntire School of Art and Architecture at the University of Virginia in 1926. Kimball likely played a major role in Kocher attending NYU and later landing his former position at the University of Virginia. Shortly thereafter, Kocher officially accepted the position of Assistant Editor to Michael A. Mikkelsen at the Architectural Record in August of 1927.

Kocher also published a series of articles in the

Record named "The Library of the Architect," which resulted in him being added to the magazine's masthead as a contributing editor in August 1926. After becoming managing editor Kocher quickly embraced modernism with the nudging assistance of

Henry-Russell Hitchcock starting in January 1928,

Douglas Haskell,

Knud Lonberg-Holm, Albert Frey, Howard Fisher Ted Larson, and others in 1929-31 and setting the magazine on a new, much more modern, course, moving its coverage to highlight building techniques, technical research and his new-found fetish for prefabrication.

(Wright and New York, the Making of America's Architect by Anthony Alofsin, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2019, note 26, p. 308).

"The Library of the Architect" by A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, 56, July 1924: 123-128; September 1924, 218-24; October 1924, 316-20; November 1924, 517-20; 57 (January 1925): 29-32.

In August 1926, Kocher was named as a contributing editor on the masthead of Architectural Record due to his fine work on the magazine's November Country House issues in 1925-27. In the November 1926 issue, Kocher's impressive 117-page article, "The Country House, Are We Developing an American Style" so impressed managing editor M. A. Mikkelsen that he hired Kocher as a fill-time member of the editorial staff at the end of the school year at the University of Virginia in August of 1927. (Notes and Comments, "Prof. Kocher Joins the Architectural Record Staff," Architectural Record, August 1927, p. 513).

"The Country House, Are We Developing an American Style?" by A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, November 1926, pp. 385-502.

At the end of his 1926 "American Country House" article, Kocher presciently predicted a new American "modernism" with his closing statement,

"Are we any nearer a realization of the old yearning for an

“American style?” Perhaps no nearer than our novelists to the “great American

novel.” But if such a style is to be achieved it will be, not by the general

adoption of any group of historic shapes and details, but by the free selection

and development of styles to meet the newer and more diverse needs of modem

life. Regional differences, the variety of local materials, and above all the

fundamental American characteristic of looking toward the future rather than

toward the past make the outlook decidedly a hopeful one. When our ruins are

unearthed, some hundreds of thousands of years hence, the archaeologist may

find twentieth century American architecture, even of the less pretentious

domestic variety, as deeply and beautifully stamped with the spirit of an age

as we now find the medieval churches of France." (Ibid., 60: 396)

Throughout the early 1920s, Professor Kocher was quite active on the Historic Resources Committee (HRC) of the American Institute of Architects, taking over the chairmanship from Fiske Kimball in 1925. In 1926, he submitted a lengthy report on the committee's activities to the president of the AIA, Milton B. Medary, Jr. In a June "exclusive" from Medary in New York to the Los Angeles Times, Kocher described in his report the public's lack of appreciation and the indifference of civic authorities among the major factors hindering the preservation of historic monuments. "Many buildings of greatest interest as historical records of our architectural growth are disappearing to make way for the ever-increasing congestion of our cities," said Professor Kocher. "Continuous watchfulness and quick action are necessary to check the loss of valuable monuments." Kocher went on to delineate many important landmarks and describe the efforts of the Philadelphia Chapter and other local chapters to save them. Two more articles on the same subject appeared in the New York Times in March and again in May of 1928. (Architects in Historic Preservation: The Formal Role of the AIA, 1890-1990, The American Institute of Architects, Washington, D.C., 1990, p. 16. "Seeks to Save Landmarks," New York exclusive, Los Angeles Times, June 21, 1926, p. 9, "Seeks Fund to Save Historic Buildings," New York Times, May 26, 1928, p. 2, "Architects Deplore Razing of Landmarks, New York Times, p. 9.). (Author's note: Valley Forge and Colonial Williamsburg were major historical landmarks Kocher's Philadelphia Chapter was concerned with during his time on the AIA's HRC and presaged his becoming a member of Williamsburg's original Advisory Committee of Architects in 1928 and in 1944 joining the Foundation staff as Editor of Architectural Records.). 1927 was a notable year for Architectural Record and managing editor Michael A. Mikkelsen, not to mention Frank Lloyd Wright. Mikkelsen signed a contract with Wright for fifteen articles at $500 each for a total of $7,500 reprising his original title "In the Cause of Architecture" which was a much-needed financial infusion for the cash-strapped Wright then in the middle of a messy divorce and facing massive bills for the recent fire repairs of his beloved Taliesin. Wright supplied five articles in 1927 and then another nine in 1928, leaving a standing joke with Record editors that he still owed them an article. (Wright and New York, the Making of America's Architect by Anthony Alofsin, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2019, pp. 195-198. See also Frederick Gutheim's Preface to In the Cause of Architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright, Wright's Historical Essays For Architectural Record, 1908-1952, Architectural Record Books, New York, 1987, p. VII).

Offices of the Architectural Record, 119 W. 40th St., New York, 1918. Shorpy.com.

In August, Mikkelsen published under "Notes and Comments" an article announcing Kocher being named to the full-time Assistant Editor position, and before the end of the year, also naming Kocher's friend Fiske Kimball and Frank Lloyd Wright's friend Andrew N. Rebori as contributing editors. In December, Kimball published a three-page article on the work of Bertram Goodhue.

("Notes and Comments, Prof. Kocher Joins the Architectural Record Staff," Architectural Record, August 1927, p. 167. Goodhue's Architecture - A Critical Estimate, Architectural Record, December 1927, pp. 537-39.

Kocher was most likely finally hired as a full-time editor due to his significant body of work for the previous six years. In addition to his historic 12-part Pennsylvania series between 1920 and 1922, Kocher also published another five-part series, "The Library of the Architect," in 1924-1925 (see above for example) and three times edited the Record's annual "American Country House" issue from 1925-1927. ("The American Country House" by A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, 58, November 1925, 401-512; 60, 385-502; 62, 337-448.). Photos of Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin were shown on pp. 309-10. (Author's note: Fiske Kimball was responsible for preparing the entire Country House issue in Architectural Record in October 1919 and was also named a contributing editor by Kocher in 1930. See also: "In Search of a Cultural Background: The Recommended Reading Lists of Alfred Lawrence Kocher and the Beauty of Utility in 1920s America" by Mario Canato, ENQ, Vol. 17, Issue 1, pp. 47-63.

Also in December of 1927, Rebori, in collaboration with Frank Lloyd Wright, authored an article entitled "Frank Lloyd Wright's Textile-Block Slab Construction." Perhaps unbeknownst to Rebori, Richard Neutra had previously written a very similar article, "Eine Bauweise in bewehrtem Beton an Neubauten von Frank

Lloyd Wright,"

while at Taliesin in 1924, which he had published in Germany in Heinrich de Fries' Die Baugilde in February 1925. (Author's note: Heinrich de Fries also edited the architectural

journal Die Baugilde and had previously published Neutra's "Die

altesten Hochhauser und der jungste Turm," describing the construction of

Chicago's Tribune Tower in his June 1924 issue before Neutra arrived at Taliesin. In March of 1925, de Fries also asked Werner Moser for Schindler's contact

information after seeing Moser's photos of Schindler's Pueblo Ribera in La

Jolla at his father Karl's house. He had also likely seen Moser's photos of Schindler's Kings Road House, in which he stayed before arriving at Taliesin in the spring of 1924. (Courtesy March 5, 1925 letter from Werner Moser to R. M. Schindler from the Schindler Collection at UC Santa Barbara graciously

translated by Gabrielle Mary Ann Schicketanz at studioschicketanz.com. After leaving Taliesin, Werner Moser also published "Frank Lloyd Wright und Amerikanische Architektur" (Freeman and Millard Houses) in Das Werk, May 1925, pp. 129-157.

From left to right; Frank Lloyd Wright Kameki Tsuchiura, Richard Neutra, Werner Moser, and Nobu Tsuchiura. From Frank Lloyd Wright, The Heroic Years: 1920-1932, Bruse Brooks Pfeiffer, Rizzoli, New York, 2009, p. 111. FLLW Fdn# 6833.0007.

Christmas Eve Concert at Taliesin II, 1924. From left to right: Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Sylva Moser, Kameki and Nobu Tsuchiura, Werner Moser, and Dione Neutra. Taliesin 1924. Ibid., FLLW Fdn# 6833024.

Neutra, Kameki Nobu Tsuchiura, and Werner Moser collaborated with Wright to put together the above book on the Los Angeles textile-block houses and other unbuilt projects designed in Los Angeles in 1922-3 and at Taliesin during 1924 which was submitted to Heinrich de Fries using Neutra's previous publishing connections described in the note above. The book was published in Berlin in 1926. (See also my "Taliesin Class of 1924: A Case Study in Publicity and Fame.").

The Life Work of the American Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, Wendingen, Amsterdam, 1925. Langmead144.

Neutra wrote to his mother-in-law in January 1925, just before he and Dione left Taliesin for California, referencing his significant assistance in preparing the above two books:

"These months and the last twelve years I have learned great things from this great master and I am very glad to show my gratitude in having carefully prepared (besides the other work) those two extensive publications which are going to appear in Amsterdam and Berlin. Holabird and Roche have sent me a wonderful reference. We shall hope that luck does not desert us at the Pacific." (Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 edited by Dione Neutra, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, 1986, p. 136. See also my "Taliesin Class of 1924").

Wright published his first five-part series, "In the Cause of Architecture," which appeared in the Record in May, June, August, and twice in October of 1927, the last three appearing after Kocher was named to the editorial staff. In the fall of 1927, Wright wrote to Andrew Rebori regarding his Los Angeles cement-block houses for an article Rebori was preparing for the December 1927 issue of the Architectural Record:

"None of the advantages which the system was designed to have were had in the construction of these models. We had no organization - Prepared the molds experimentally...

None of the accuracy which is essential to the economy in manufacture nor any benefit of organization was achieved in these models....The blocks were made of various combinations of the decayed granite and sand and gravel of the sites - The mixture was not rich - Nor was it possible to cure the blocks in sufficient moisture. The blocks might well have been of better quality.

Some unnecessary trouble was experienced in making the buildings waterproof. All the difficulties met with were due to poor workmanship and not to the nature of the scheme.

But it is seldom that buildings of a new type are built outright as experimental models with less trouble than were these notwithstanding our lack of organization and our concentration on invention." (Frank Lloyd Wright to A. N. Rebori, September 15, 1927. From Wright in Hollywood by Robert Sweeney, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1994, p. 118).

Perhaps working from a copy of the above De Fries book in collaboration with Wright, Rebori used some of the exact same illustrations, including renderings of the Freeman (see below) and Ennis Houses, likely by Kameki or Nobuku Tsuchiura, and Neutra's "Textile-Block Slab Construction" diagram seen below, in his Architectural Record article. Rebori observed that "Wright has succeeded in breaking the old traditions by making use of mechanical methods, modern structural forms and their application by the shaping of monolithic masses and finally by devising a method of building construction calling for the use of ornamented reinforced blocks."

Residence of Samuel Freeman, Hollywood, California, Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect, "Frank Lloyd Wright's Textile-Block Slab Construction," by A. N. Rebori, Architectural Record, December 1927, p. 451. Langmead 162.

Ibid., p. 465. The above diagram was drawn by Richard Neutra at Taliesin in 1924. Langmead 162. See also Sweeney, pp. 231-2. (See much more on the exact replication of illustrations from the book used in Rebori's article at my "Taliesin Class of 1924: A Case Study in Publicity and Fame."). January 1928 was definitely a major turning point in the Architectural Record. Kocher's influence was becoming readily apparent, as can be inferred by reading Mikkelsen's opening editorial titled, "A Word About the New Format." Mikkelsen wrote about the new page size standardization, the typographical design, and the new Garamond type provided by Frederic W. Goudy, as well as the new design layout. He paid tribute to Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright's influence in the evolution of architecture and presciently ended his piece with,

"Possibly the impulse originated by Sullivan, developed by Frank Lloyd Wright and amplified abroad will bring repercussions from Europe. No doubt standardized shapes and machine-made surfaces will find their places in design. That there will be movement, enterprise, new feeling is clear from the evidence we - more particularly my colleague A. Lawrence Kocher - have taken pains to bring together in the present number." ("A Word About the New Format," Michael A. Mikkelsen, Architectural Record, January 1928, pp. 1-2.)

The Architectural Record kicked off 1928 by trumpeting a brand new format in the January issue. From the time Mikkelsen and Kocher named Henry-Russell Hitchcock a contributing editor in January of 1928, the magazine immediately struck a more modern path. For example, January's issue included Hitchcock's review of the first English edition of Le Corbusier's Towards A New Architecture." (See below).

"The polemical book contains seven essays, each of which dismisses the contemporary trends of eclecticism, replacing them with architecture that was meant to be more than a stylistic experiment; rather, an architecture that would fundamentally change how humans interacted with buildings. This new mode of living derived from a new spirit defining the industrial age, demanding a rebirth of architecture based on function and a new aesthetic based on pure form." (Amazon blurb).

Towards a New Architecture (Vers une Architecture) by Le Corbusier, First English translation by Frederick Etchells, Payson and Clark, Ltd., New York, 1927. (The American edition was actually printed in England from sheets supplied by the English publisher. See note 71 on p. 326 of Le Corbusier in America by Mardges Bacon, MIT Press, 2001.).

"As a critic, editor, and curator, Hitchcock was largely responsible for constructing the dominant view of modernism in America, based almost exclusively on his interpretation of the moralist canon of the European modern movement. He came to be identified as Le Corbusier's principal supporter in America. Hitchcock first read Vers une Architecture before its appearance in translation while he was working toward a masters degree at Harvard from 1925 to 1927. As graduate students, he recalled, "we had our own copies of one of the Paris issues, soon worn out by repeated reading. "In the spring of 1927 Hitchcock gave his first lectures at Wellesley and "emphasized Corbu."(Le Corbusier in America, Bacon, p. 19. "Modern Architecture - A Memoir," Hitchcock, JSAH 27, (December 1969), p. 229.)

Monographs by Corbusier, 1912-1931, from Le Corbusier, Architect of Books by Catherine De Smet, Lars Muller, Baden, 2005, p. 121.

Hitchcock's enthusiastic and premonitory January 1928 review of Towards a New Architecture began with a strong statement of support for his design of the Palace of the League of Nations being the entry most deserving to be built. Later in the review he deemed Corbusier's book "the one great statement of the potentialities of and architecture of the future and a document of vital significance," notwithstanding its "broken style" and "irritating" frequency of "repetitions." (Ibid., Hitchcock, review of Towards a New Architecture, Architectural Record, January 1928, pp. 90-91. Frank Lloyd Wright reviewed the same book in the September 1928 issue of World Unity, pp. 393-5).

Ennis House, Los Angeles by Frank Lloyd Wright, 1924 from Architectural Record, January 1928, p. 56. Langmead 179.

In the January 1928 issue, Kocher also published the first of a new nine-part series of illustrated articles throughout 1928 of Frank Lloyd Wright's "In the Cause of Architecture" series, i.e., "I - In the Logic of a Plan." Wright essentially continued Rebori's work from the previous month. He included in his article the same floor plan of the Unity Temple as well as floor plans of both the Coonley and Martin Houses, which also appeared in Heinrich de Fries's Frank Lloyd Wright: aus dem Lebenswerke eines Architekten. Wright's article ended with a rendering and floor plans of the Ennis House in Los Angeles. (See above). The exact same rendering and floor plan had been published by de Fries in Germany in 1926. (See below. Also see much more in my "The Taliesin Class of 1924: A Case Study in Publicity and Fame").

Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright in Frank Lloyd Wright: aus dem Lebenswerke eines Architekten edited by Heinrich de Fries and Frank Lloyd Wright, Verlag Ernst Pollak, Berlin, 1926, p. 55.

The idea for the Record to publish another series of Wright's "In the Cause of Architecture" essays was used by Mikkelsen and Kocher to help soften the blow to Wright's ego for Hitchcock writing a review of Le Corbusier's recently translated edition of Towards A New Architecture which was included in the same issue. In doing so, Kocher was making a bold step towards the acceptance of modernism with the fervent assistance of Hitchcock. Wright appeared again in February with "II. - What Styles Mean to the Architect," which included three photos of the Barnsdall House, perhaps by Willard Morgan, also Richard Neutra's photographer. Wright's part "III - The Meaning of Materials - Stone" appeared in April. Again, Wright used an identical image of the Imperial Hotel, which was previously published by de Fries in 1926 (see below), along with images of Taliesin and an architectural detail of the Barnsdall House. (Langmead 179-181. Also see also my "Willard D. Morgan: The Early Architectural Photography Connections.").

Garden Bridge, North Pool and Elevator Housings, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo. DeFries, p. 5. Also in "In the Cause of Architecture, III. The Meaning of Materials - Stone," by Frank Lloyd Wright, Architectural Record, April 1928, p. 351. Langmead 181.

Also in April Hitchcock made another impassioned plea for Corbusier's Palace of the League of Nations to be the final choice for being built because of the fact that Corbusier's design was based on the original budget of 13,000,000 francs and since the budget had since been raised 50% to 19,500,000 francs, "thus permitting the choice of not a modern design but on frankly imitative of the past. ... That in the first place, this is dishonest toward the modern competitors who worked within the original financial limitation is immaterial." Hitchcock referenced in his article Cobusier's previously published League of Nations entry in the September 1927 issue of Cahiers d'Art and the current issue of L'Architecture Vivante. The following number of Cahiers d'Art included three articles that positively favored Corbusier's entry and over 20 letters to the editor promoting Corbusier and a list of over twenty publications where his entry was favorably published. (Hitchcock, "The Designs for the Palace of the League of Nations," Architectural Record, April 1928, p. 182. Project Pour Le Palais De La S. D. N. a Geneve Par Le Corbusier et P. Jeanneret, Cahiers d"Art, Number 6, September 1927, pp. 175-179. "Who Will Build the Palace of Nations?" by Christian Zervos, Cahiers d'Art, Numbers 7-8, 1927, pp. I-VIII. "The Masters of Architecture Demonstrate," "The Professional Associations Take Action," "The European Press Speaks Out," Ibid., Number 9, pp. IX-XVI.)

Le Corbusier took advantage of the scandal and hoopla surrounding his not being selected to build the Palace of the League of Nations to publish Une Maison-Une Palais, a manifesto of sorts illustrating his extreme displeasure with the jury's decision and to also lay the foundation for the formation of the Congres Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). (See also my "Albert Frey: The Formative Years, 1925-1930").

"The scandal accompanying the elimination of (Corbusier's) design, however, gave him needed publicity by identifying him with modern avant-garde architecture. An immediate consequence of the Geneva affair was the creation, in La Sarraz, Switzerland, in 1928, of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) which was oriented toward city planning theory. Le Corbusier, as secretary of the French section, played an influential role in the five prewar congresses and especially in the fourth, which issued in 1933 a declaration, intended at first to defend the avant-garde architectural values defeated in Geneva. By 1930 the organizatio

n elaborated on some of the basic principles of modern architecture." (From Britanica)

Richard J. Neutra and R. M. Schindler, Los Angeles, Architects, Palace of the League of Nations, Geneva, 1926. From Internationale Neue Baukunst by Ludwig Hilberseimer, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927, p. 9.

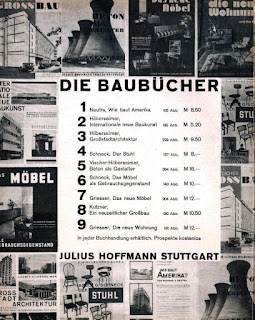

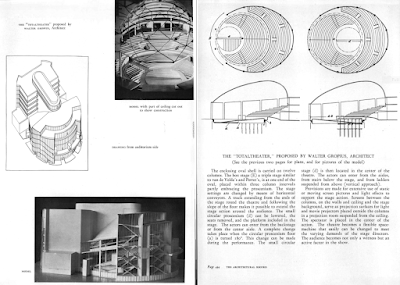

Hitchcock likely saw Neutra and Schindler's League of Nations entry in Ludwig Hilberseimer's Internationale Neue Baukunst, which was published at the same time as Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika? as a part of a series of nine books by the same publisher, Julius Hoffmann, in Stuttgart. (See below for example.). Hitchcock never mentioned having seen this project in any of his later writings, strongly signaling his preference for Corbusier's version, which he wrote positively about on at least three occasions. Hitchcock soon reviewed Neutra's book in the June 1928 issue of Architectural Record.

Julius Hoffmann Baubucher ad, Moderne Bauformen, April 1931, p. 98.

The above League of Nations design competition entry

exhibits elements of Schindler's recently completed Lovell Beach House and

Neutra's early 1920s employer Erich Mendelsohn projects. Neutra took advantage of knowing that one

of the judges for the competition would be none other than Karl Moser, his

former Swiss professor friend and the father of his 1924 Taliesin mate, Werner Moser. Since Werner

had also previously visited Schindler and corresponded with him from Taliesin, chances seemed

good that the duo might win a prize with their entry. The project won no prize

but was exhibited in Stuttgart at the July 1927 exhibition of the German Werkbund beside the entries of Corbusier and Hannes Meyer. (See exhibition poster below.) Schindler's participation initially went uncredited due to a miscommunication

by Dione Neutra's parents, who were shepherding the design entry through the

competition process. Thus, the Hilberseimer publication was likely the first opportunity that Neutra

had to correctly credit Schindler's role in the design. (See Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture by Thomas S. Hines, Oxford University Press, 1982, pp. 70-3, much more. Author's note: Coincidentally, Corbusier asked Karl Moser in 1926 if he knew of anyone in his recent graduating class who might be useful in working on his League of Nations design competition entry, and Moser recommended Alfred Roth, who immediately moved to Paris to begin work. Author's note: William Lescaze also included the League of Nations in his design resume for MOMA's 1932 Modern Architecture, International Exhibition, p.148).

German Werkbund Weissenhof Estate Exhibition Poster, Stuttgart, July - October, 1927. From

The May 1928 issue of the Record continued the Wright series with "In the Cause of Architecture, IV. The Meaning of Materials - Wood" which again included an image from de Fries, this time a rendering of a project completed by Kameki Tsuchiura while in Los Angeles in 1923, "Tahoe Cabin, Shore Type."

Tahoe Cabin, "Shore Type", Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect. From "In the Cause of Architecture, IV. The Meaning of Materials - Wood," Architectural Record, May 1928, p. 482. Also in De Fries, p. 53. Langmead 182.

Hitchcock also published a two-part series, "Modern Architecture, I. The Traditionalists and the New Traditionalists and II. Modern Architecture, The New Pioneers" in the April and May 1928 issues, respectively. These articles were a preview of his book Modern Architecture, Romanticism and Reintegration, to be published the following year. Hitchcock's Modern Architecture series ran side-by-side with Wright's "In the Cause of Architecture" essays, causing Hitchcock to be very tactful in how he described the importance of Wright. He labeled him the best of the New Traditionalists, along with Eliel Saarinen of Europe. On Wright, he wrote,

"On the one hand there exists the work of such a complete "modernist" as Frank Lloyd Wright, who is no mere follower of European fashions rather is he the founder of a tradition much followed in Europe. On the other is the modern building of America in the field of architecture and above all in that of engineering beneath the ever thinner coat of applied design. ... The New Traditionalists are related in America to Wright whom they revere as one of the founders of their New Tradition both in his work and in his writing." ("Modern Architecture I, The Traditionalists and the New Tradition," by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architectural Record, April 1928, pp. 337-349.

Hitchcock's "Modern Architecture, II. The New Pioneers" listed his obvious favorite, Le Corbusier, along with Walter Gropius, Mies Van Der Rohe, and J. J. P. Oud, and also included illustrations of Corbusier's and Oud's work. Still conscious of Wright's ego, he added,

"Oud, one of the greatest of the New Pioneers, writing in

1925 a tribute to Wright in the Wendingen Monograph, implies that the New

Pioneers fulfill the demands of Wright as a theoretician better than those who

follow him more directly and even perhaps better than Wright himself, whose

talent is too broad to be tied even by his own theories (which appear to me at

least to be in advance of much of his practice)." ("Modern Architecture II, The New Pioneers," by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Ibid., May 1928, pp. 453-460.).

Befreites Wohnen by Sigfried Giedion, Lars Muller Publishers,

Zurich, 1929. Includes photos of Neutra's Jardinette Apartments.

William Lescaze about this time was acting as a cultural bridge of sorts with his 1929 correspondence and trip to Europe either contacting or visiting in person Richard Neutra, Le Corbusier, Andre Lurcat, Mallet-Stevens, J. J. P. Oud and many other modern architects about sending him photos of their work and possibly sending him statements of their architectural philosophies for a proposed book, perhaps taking inspiration from Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika? For example, after corresponding with Lescaze, Christian Zervos, editor of Cahiers d'Art, published an essay on new American Architecture, which included Neutra's Jardinette Apartments. Jardinette was also published in Siegfried Giedion's 1929 Befreites Wohnen. That is the likely reason that Neutra included Lescaze's work in his second book, Amerika, in 1930, as seen later below. (Europe Meets America, William Lescaze, Architect of Modern Housing, by Gaia Caramello, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, London, 2016, pp. 37-41. Author's note: Gideon compiled Befreites Wohnen in conjunction with the CIAM II conference in Frankfurt, Germany, and included a floor plan of a minimum Jardinette apartment in the CIAM II conference proceedings under the title Die Wohnung fur das Existenzminimum.

Gropius in Arizona, 1928. From Gropius, An Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus by Reginald Isaacs, Little, Brown and Co., Boston, 1991, p. 147.

Taking advantage of his resignation from his Bauhaus directorship, in April and May of 1928, Gropius and his wife Ise fulfilled a long-held dream by touring the United States to learn more about construction techniques, planning methods, and building "steel homes." He had already seen, and been impressed by, Richard Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika? evidenced by his inclusion of Neutra's "Rush City" skyscraper in the second (1927) edition of his Internationale Architektur. A visit to Neutra in Los Angeles in May resulted from a mutual lifelong admiration and friendship, and a tour of motion picture studios, industrial areas, and oil rigs in Long Beach, as well as the work of Schindler and Frank Lloyd Wright. (Ibid., p. 149.).

After Gropius returned to New York, Kocher came to the Plaza Hotel, where Gropius was staying, to meet him and invite him to contribute an article. He also met Robert Davison of the housing institute at Columbia University at the same time and invited him to write an article to accompany that of Gropius. (Isaacs, pp. 149-150. Author's note: Kocher soon named Davison as a contributing editor, and they later co-authored an article, "Swimming Pools - Their Design and Construction," for the January 1929 issue of Architectural Record, pp. 67-87. Kocher featured Gropius in Architectural Record more than ten times between 1928 and 1936. Bauhaus in America, Margret Kentgens-Craig, p. 200.).

Wie Baut Amerika? by Richard J. Neutra, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927. R. M. Schindler's 1924 P

Pueblo Ribera, La Jolla, California, R. M. Schindler, architect, 1923-24. From Wie Baut Amerika? by Richard Neutra, pp. 36-37 and front cover. Photos likely by Clyde Chace or R. M. Schindler. Pueblo Ribera in La Jolla is shown on the upper left of the cover.

In the June 1928 issue of the Record, Hitchcock reviewed Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika?, which had been reviewed over a year earlier in the February 1927 issue of Das Werk by editor Joseph Gantner and in the Russian Journal "Contemporary Architecture." Gantner used three Kameki Tschiura construction photos of the Storer House from Neutra's book to compile another article on Frank Lloyd Wright's cement-block houses in the same issue. Some of the Storer House photos were also published in de Fries in 1926. The book was additionally reviewed by the Russian journal "Contemporary Architecture" in 1927. This three-page review included seven construction photos and a floor plan of the Palmer House Hotel taken while Neutra was working for Holabird and Roche in Chicago in 1924 before joining Wright, Werner Moser, and the Tsuchiuras at Taliesin. ("Mechanisierung und Typisierung des Serienbaus" by Joseph Gantner, Das Werk, February 1927, p. XXIII. "Die Zementblock-Bauweise von Frank Lloyd Wright" by Joseph Gantner, Das Werk, February 1927, pp. XXIII-XXIV, "Amerikanische Baustelle, Frank Lloyd Wright," Ibid., p. 64. "Corbusier's "Die Neuen Wohnviertel Fruges in Pessac (Bordeaux), Ibid., pp. 57-58. "). (Author's note: Neutra and fellow 1924 Taliesin-mate Werner Moser each published articles in Das Werk in May 1925. "Frank Lloyd Wright und Amerikanische Architekture" by Werner Moser, Das Werk, May 1925, pp. 129-142 (including 19 photos of FLW projects and 1 of the Tribune Tower under construction) and Neutra's "Architekten und Bauwesen in Chicago," (including Burnham & Root's Monadnock Building, Louis Sullivan's Carson Pirie Scott Building and plans of FLW's Freeman House), Ibid., pp. 143-145, Both articles included material shared at Taliesin in 1924 with some of Moser's also included in de Fries, 1926. Also appearing in this issue was "Amerikanische Architektur und Stadtbaukunst," by Joseph Gantner, Ibid., pp. 146-141, including floor plans, site plans, and elevations of FLW's" Millard House, Taliesin, and houses in Chicago and Riverside.

Henry-Russell Hitchcock "discovered" Neutra in a somewhat ironic manner in early 1928 while he was scouring foreign periodicals and books for potential candidates for what would eventually become his and Philip Johnson's visionary "International Style" exhibition at MOMA in 1932. Hitchcock also ran across a copy of Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika? and wrote a favorable review in the June 1928 issue of the Record, an excerpt of which reads,

"The central third of the book is devoted to a discussion in great detail of the New Palmer House in Chicago as a typical example of American large-scale city building. ... The concluding section is again, like the introduction, to a large extent theoretical and takes up various new methods of construction for use in small scale buildings." ("How America Builds," by Richard Neutra. Review by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architectural Record, June 1928, pp. 594-5.).

Skyscraper from "Rush City" from Wie Baut Amerika? by Richard Neutra, Josef Hoffmann, Stuttgart,1927, p. 73. (This rendering also appeared in Internationale Architektur (second edition) by Walter Gropius, in 1927, the Die Wohnung exhibition held in conjunction with the Weissenhof Exposition in Stuttgart in 1927, and Modern Architecture: Romanticism and Reintegration by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, 1929.).

While describing the content of Neutra's book, Hitchcock particularly liked his "Rush City" drawings and singled out the above skyscraper rendering with, "There is also a design of his own for the exterior of an office building which has the practical and artistic advantages of contemporary factory design unobscured by masonry wall-filling and cast ornament."

"Knitlock" System, Ibid., pp. 58-59.

Seemingly having difficulty with the book's German language, he erroneously compared former Wright apprentice Walter Burley Griffin's patented "Knitlock" system illustrated in Neutra's book with Wright's California cement-block houses. Rebori also unwittingly used Richard Neutra's original "Textile-Block Slab Construction" diagram in his December 1927 Record article without properly crediting him. For example, Hitchcock wrote,

"[Neutra] also discusses the "Knitlock" system of reinforced construction used in the last few years by Frank Lloyd Wright in his California houses already described by Andrew Rebori in The Record." (Ibid., p. 594.)

Echoing Gropius's recent admiration of the Southwest in his book, Hitchcock concluded with, "Finally, for the comfort of the retrospectively minded are a few illustrations of Pueblo architecture today so universally admired and an ingenious indication of the parallelism of its aesthetic with the aesthetic of the architecture of Rush City." (Albert Frey would have his then partner, Kocher, publish his own photo of the Taos Pueblo in the May 1934 issue of Architectural Record seen elsewhere herein.).

Taos Pueblo from Wie Baut Amerika?, p. 74. Photos by Richard Neutra.

Taos Pueblo, October 1915. Photo by R. M. Schindler. Schindler Collection, UC-Santa Barbara.

Frank Lloyd Wright's "In the Cause of Architecture" (ITCA) series also continued in the June issue with "V. The Meaning of Materials - The Kiln." The article was illustrated with images of the Larkin Building and the Robie and Cheney Houses, the former also appearing in de Fries in 1926. Hitchcock again ended the issue with a review of "Foreign Periodicals." (Ibid., pp. 555-562, 598-600. Langmead 183).

The Sowden Home, Hollywood, California, Lloyd Wright, Architect. Architectural Record, July 1928, p. 10. Photo by Willard D. Morgan. Langmead 184.

July's issue continued Wright's ITCA series with "VI. The Meaning of Materials - Glass," which was prefaced with a Willard Morgan photo of Lloyd Wright's Sowden House that Morgan had published the previous year in the August 1927 issue of Popular Mechanics under the title "Glass Roof Lights House Without Windows." Lloyd's work was considered worthy enough to be associated with his father in this article. The article also included images of the Barnsdall House and the Freeman House, which were also likely by Morgan, and the Robie House. Hitchcock finished off the July issue with another book review, "City Planning of Today," and ended with his monthly review of "Foreign Periodicals." (Ibid., July 1928, pp. 10-16, 84, 87-88.).

Freeman House, Los Angeles, Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect. (Ibid., August 1928, p. 100.). Photo likely by Willard D. Morgan. Langmead 185.

Left: Temporary residence of Frank Lloyd Wright and Olga Ivanovna, 228 Coast Blvd., La Jolla, California, 1928. From "The Wright Library" at Steinerag.com. Right: "Wife Wrecks Architect's Love Nest," Oakland Tribune, July 14, 1928, p.1.

Frank Lloyd Wright was living a nomadic existence since January 1928, fleeing either his creditors or Miriam while acting as a consultant for the design and construction of the Arizona Biltmore Hotel and the design of San Marcos in the Desert. During this time, he was still submitting his second nine-part series, "In the Cause of Architecture" (ITCA), of articles to Kocher. After moving three times in Phoenix, he fled to La Jolla to escape the summer heat of the desert, where Miriam still was able to track him down. (See above right). (Author's note: Wright and Ogilvanna had spent the summer of 1927 there as well, evidenced by a folksy July 1927 letter from Dione Neutra to her mother in which she described the house and enjoying an ocean swim with Wright. She also referenced the photos she sent of Schindler's [Lovell] beach house. (Promise and Fulfillment, pp. 166-7). (Author's note: During the Neutra visit in the summer of 1927 Wright was then in the midst of preparing a five-part "In the Cause of Architecture" series for Michael Mikkelsen's Architectural Record: May 1927,"Part I-The Architect and the Machine," June, "Part II-Standardization, The Soul of the Machine," August, "Part III-Steel," October, "Part IV-Fabrication and Imagination," "Part V-The New World.").

Wright continued with the second ITCA series in August with "Part VII. The Meaning of Materials - Concrete," which included more Morgan photos of the Freeman, Ennis, and Millard Houses. Wright included the following note at the end of the article, perhaps after hearing from his son about the confusion caused by the use of his son's Sowden House to prominently preface his own article on glass.

("Note - Since writing the above, I have found in the Sowden House at Los Angeles, built by my son, Lloyd Wright, a treatment of the block that preserves the plastic properties of concrete as a material. An illustration of this house appears on p. 10 of the July issue of The Architectural Record. (Ibid., pp. 98-104.). (See also my "Willard D. Morgan: The Early Architectural Photography

Connections.").

Left: Invitation to the wedding of Frank Lloyd Wright and Olga Ivanovna, Rancho Santa Fe, California, August 25, 1928. From Steinerag.com. Right: Living Room of Lovell Beach House, Newport Beach, California, 1928. From left: R. M. Schindler on balcony, Samuel and Harriet Freeman, and Dione Neutra on sofa. Photo likely by Richard Neutra. The party was most likely en route to the Wright wedding in Rancho Santa Fe.

Frank Lloyd Wright designed his own invitation to his August 25, 1928, wedding invitation in Rancho Santa Fe, sent to a close-knit group of friends, most likely including former clients Sam and Harriet Freeman and former employees R. M. Schindler and the Neutras. (See above right). The invitation included a photo of Frank and Ogilvanna's illegitimate three-year-old daughter, Iovanna. The wedding took place one year to the day from Wright's divorce from Miriam Noel Wright. The family honeymooned at the elegant El Tovar Hotel at the Grand Canyon. (Alofsin, p. 113).

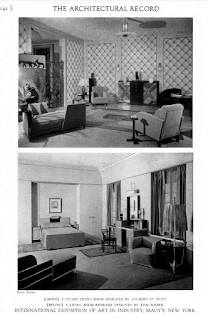

A Living Room-Bedroom Designed by Kem Weber, International Exposition of Art in Industry, Macy's, New York. (Ibid., August 1928, p. 142.).

Also in the August issue was an article, "The Macy Exposition of Art in Industry," which included two images of work by Schindler-Neutra Los Angeles coterie member Kem Weber. The exposition also included work by former Karl Moser student William Lescaze, who, a few years later, would share with Architectural Record Managing Editor A. Lawrence Kocher the architectural services of former Corbusier apprentice Albert Frey. Weber's installations included the artwork of Schindler-Neutra coterie members Edward Weston, Henrietta Shore, and Peter Krasnow. (See my "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad" for much more detail on this. William Lescaze came to America for the first time in 1920 after graduating from studying under Karl Moser in Switzerland, and a second time in the company of Karl Moser's son, Werner, in 1924. From Modern Architecture, International Exhibition, Hitchcock, Museum of Modern Art, 1932, p. 144).

Penthouse Studio Apartment, William E. Lescaze, Architect, International Exposition of Art in Industry, Macy's, New York, Ibid., August 1928, p. 138.

Um de Neue Gestaltung, Amerika, (Jardinette Apartments, Hollywood by Richard Neutra, Architect). Das Neue Frankfurt, April 1928, pp. 68-9. Photos by Willard D. Morgan.

Frank Lloyd Wright ended the issue with an excellent review of Fiske Kimball's latest book, American Architecture. Wright's wit must have filled Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson with glee as they envisioned their new, glorious future for "International Style" architecture. Hitchcock again wrapped up the issue with his monthly review of "Foreign Periodicals," in which he mentioned the April 1928 issue of Das Neue Frankfurt and Neutra's "New Apartments in Los Angeles" (see above). (Ibid., August 1928, pp. 172-3.)

New Dimensions, The Decorative Arts of Today in Words and Pictures by Paul Frankl, Payson & Clark, New York, 1928. Langmead 173. NYPL Digital Collections.

Paul Frankl, William Lescaze, Eugene Schoen, and three other artists formed the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen (AUDAC) in New York in 1928 to promote modern design. Around this time, Paul Frankl's book

New Dimensions (see above left) was published by Payson & Clark in the spring of 1928. Frank Lloyd Wright agreed to write the

foreword to Frankl's book in appreciation for Frankl and AUDAC naming him an honorary member. Frankl

dedicated the book to him as well. Wright had first befriended Frankl at his New York gallery in 1926.

(Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design, Christopher Long, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, pp. 111-113. Europe Meets America, William Lescaze, Architect of Modern Housing, by Gaia Caramello, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, London, 2016, p. 31)."Frankl cited Wright in a 1927 House & Garden essay "as proof that America already had a spirit capable of adapting itself to "the new." Frankl maintained that, "Its richly creative designers had a major advantage in producing their own version of modernism: "If possession is nine-tenths of the law, then everything is in our favor; it was an American who created the entire current of modern architecture and decorative art: Frank Lloyd Wright." (Wright and New York, The Makings of America's Architect, Anthony Alofsin, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2019, p. 87 and note 36, p. 292).

"Private Office and Reception Room of Payson & Clark, Publishers, New York, by P. T. Frankl, both in 'Some American Interiors in the American Style," by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architectural Record, September 1928, pp. 235-243.

Henry Russell Hitchcock featured interiors by Paul Frankl (see above), William Lescaze, Paul Nelson, and others in a nine-page article in the September issue of the Record. Clearly evidencing that he read Frankl's new book, he included two photos of his skyscraper furniture adorning the walls of rooms in his publisher, Payton & Clark's offices. Hitchcock followed with another thoughtful piece in the "Notes and Comments" section entitled "Two Books That Exist and Two That Do Not." He described the differences between Lewis Mumford's Sticks and Stones and Fiske Kimball's recent American Architecture and generally praised both efforts. ("Notes and Comments, Two Books That Exist and Two That Do Not," Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Ibid., pp. 252-3).

Left: "Window Corner in a Living Room Exhibited at Loesser's Department Store, Brooklyn, by William Lescaze, Architect, Architectural Record, September 1928, p. 241 in "Some American Interiors in the American Style," by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architectural Record, September 1928, pp. 235-243. Right: "Stage for a Modern Department Store," William Lescaze, Architect, Amerika, p.102.

"Amerika, Korperubung und Gegenwartige Bauarbeit," Richard Neutra (Lovell Physical Culture Center, Health House and Beach House), Das Neue Frankfurt, May 1928, pp. 90-92). Photos by Willard D. Morgan.

Lastly, in his Review of Foreign Articles column, he made mention of Das Neue Frankfurt, "providing very small photographs of the significant work of Neutra and of Schindler in California, which The Record hopes to soon show fully." He was likely referring to the May issue seen above which included images of Neutra's Physical Culture Building in Los Angeles for Dr. Lovell, two of his preliminary drawings of the Lovell Health House in Los Angeles and Dr. Lovell's Beach House in Newport Beach designed by his landlord R. M. Schindler and a then unrelated article on Brinkman and Van Der Vlugt's below Van Nelle Tobacco Factory in Rotterdam for Neutra's future patron Cees Van Der Leeuw. (See above). (Architectural Record, September 1928, pp. 235-243, 252-3, 263-264.).

"Neue Hollandische Fabriksbauten," (Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam) by Brinkman and Van De Vlugt, Ibid., p. 93.

Kocher wrote an article for the October issue, "Color in Early American Architecture, With Special Reference to the Origin and Development of House Painting." pp. 278-290. Wright's ITCA series continued with "VII. Sheet Metal and a Modern Instance" pp. 334-342, (Langmead 186). Hitchcock contributed an article on "Housing," pp. 346-7, and "Foreign Periodicals," singling out L'Architecture Vivante for its excellent coverage of Le Corbusier, Oud, Van Der Rohe, and Gropius on pp. 353-354.

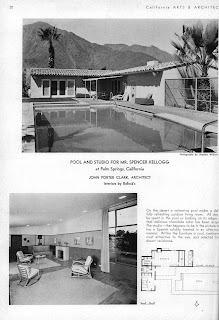

Design for a Two-Family Country House, Bensel, Kamps & Zeigler, Architects, Architectural Record, November 1928, pp. 421-2.

November brought about an introduction of sorts to Kocher's soon-to-be partner,

Gerhard Zeigler, with the publication of two of his proposed two-family country house projects, which were included in William Lescaze's article on a modern take on the genre, "The Future American Country House," and Lescaze's proposed country house of 1938, seen below.

"An American House in 1938," William Lescaze, Architect, Ibid., November 1928, pp. 417-422.

Gerhard Zeigler would soon become Kocher's business partner until he returned to Germany in May of 1931 and was replaced by Swiss architect Albert Frey, an erstwhile apprentice in Corbusier's atelier in Paris, as described later herein. (Author's Note: Frey would also work part-time for Lescaze in 1931, per Joseph Rosa in Albert Frey, Architect, Rizzoli, New York, 1990, p. 150.).

Joseph Urban's Facade of the Max Reinhardt Theater from the Internet.

December brought about a lengthy article, "The Reinhardt Theatre, New York, Joseph Urban, Architect," by Urban's assistant,

Shepard Vogelgesang. Urban was soon to be very helpful in collaborating with Schindler and Neutra in scoring exhibition space for California modern architects and designers at the New York Architectural League's 50th anniversary exhibition in 1931, as will be discussed in much more detail later herein. Frank Lloyd Wright's ITCA series continued with "IX. - The Terms," and Hitchcock again updated with his monthly review "Foreign Periodicals," in which he mentioned another appearance of Neutra apartments (Jardinette) in the July 1928 issue of Die Baugilde. (Architectural Record, December 1928, pp. 461-465, 507-514, 537-39. Langmead 187).

An Exposition of Decorative Arts of Today exhibition catalogue, Bullock's, December 1928. Catalogue design by Jock Peters. Courtesy of the UC-Santa Barbara, University Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Jock Peters Collection.

Also in December 1928, Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler, Jock Peters and Kem Weber were included in an exhibition at the Bullock's Los Angeles downtown store curated by UCLA art instructors Annita Delano and Barbara Morgan (Willard's wife), which also included work by herself and artists Henrietta Shore, Peter Krasnow, Edward Weston and others in the Schindler-Neutra orbit.

(See much more detail on this at my "Foundations.").

Jock Peters portrait by Brett Weston, 1930. Jock Peters Collection, U-C, Santa Barbara.

Delano's Bullock's exhibition was undoubtedly the genesis

for Pauline Schindler's March 1930 decision to organize and curate a traveling

exhibition of Contemporary Creative Architecture in California (see announcements later below) featuring Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, R. M.

Schindler, Jock D. Peters, Kem Weber and J. R. Davidson for the

Western Association of Museum Directors, write a book featuring their work and

act as their agent for booking lectures. Nothing ever came of the book project. (See agent contract proposal later below. McCoy, p. 58).

Residence of Mr. and Mrs. [James] E. How, Los Angeles, R. M. Schindler, Architect. Architectural Record, January 1929, pp. 5-9.

Exclusive of Frank Lloyd Wright, R. M. Schindler was the first modern architect in Los Angeles to have a full house project article published in the Architectural Record, making it in January 1929

with his How House designed for Chicago Hobo King James Eads How in 1924. Neutra had previously published elevations, floor plans, and a cross-section of Schindler's How House in the September 1928 issue of Das Neue Frankfurt, along with his Conrad Buff Studio project and Frank Lloyd Wright's Freeman House and Irving Gill's Dodge House. That success prompted Schindler to commission photographer Viroque Baker to properly photograph the project and submit his own article to Kocher. (See above. Author's note: Pauline Schindler was also involved

in James Eads How's Hobo movement during her Chicago Hull House days. This relationship resulted in her

husband receiving a commission to design a Los

Angeles house for How in 1924. See, for example, my "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School."). (Author's note: Neutra misidentified Irving Gill's Dodge House as the MacKenna House, the name of the current owner, when he submitted this article to Das Neue Frankfurt in 1928 and later corrected his mistake in his 1930 book Amerika.).

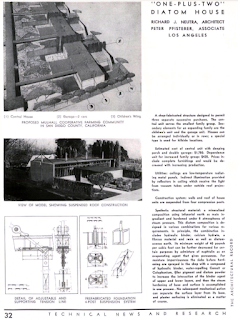

The same issue also included the inauguration of the Technical News and Research Department, which contained a lengthy article on swimming pool design by A. Lawrence Kocher and Robert L. Davison. This resulted in Davison being anointed as associate editor the following month. Hitchcock contributed another brief article on the restoration of "The Boston State House." ("Swimming Pools, (Standards for Design and Construction)," by A. Lawrence Kocher and Robert L. Davison, Architect. Architectural Record, January 1929, pp. 68-87, The Boston State House, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Ibid., p. 98. See also The Portfolio and the Diagram, Architecture, Discourse and Modernity in America by )

Rendering of Sunlight Towers by A. Lawrence Kocher and Gerhard Zeigler, architects. Architectural Record, March 1929, pp. 307-310.

In time, Kocher and Gerhard Zeigler became partners to design a project, "Sunlight Towers," which Hugh Ferriss delineated for the March issue of Architectural Record. The two remained partners until May of 1931, when Zeigler returned to Europe. To ingratiate himself with Kocher, Richard Neutra also published a Sunlight Towers floor plan in his 1930 book Amerika. (See below. Author's note: The floor plan below also appeared in.

Sunlight Towers floor plan by A. Lawrence Kocher and Gerhard Zeigler, from Amerika by Richard Neutra, Verlag Anton Schroll, Wien, 1930, p. 121. (Also Ibid., p. 308.).

Garden Apartment Building, Los Angeles, Richard J. Neutra, Architect, Architectural Record, March 1929, p. 270. Photos by Willard D. Morgan.

After Hitchcock twice favorably mentioned Neutra's Jardinette (Garden) Apartments in his 1928 "Foreign Periodicals" column, it was inevitable that Kocher himself would finally publish two stunning Willard Morgan images in the March 1929 issue, included in a major piece by Henry Wright on "The Modern Apartment House."(See above.).

Willard Morgan image of the Jardinette Apartments by Richard Neutra, ca. 1927. Courtesy of Lael Morgan.

Interior of Kaufmann's Dining Room, Pittsburgh, Kem Weber, Designer, Architectural Record, April 1929, pp. 315-320.

April of 1929 led off with "Some Recent Work of Kem Weber." Building upon his success from the Macy's Exposition published last year, the article featured his dining room for the Kaufmann Department Store in Pittsburgh. (See above). The issue continued with a lengthy article "Tendencies of the School of Modern French Architecture," which included work by Michel Roux-Spitz, Patout, and Le Corbusier. (See below).

A Villa in Vaucresson, France, Le Corbusier, Architect, Architectural Record, April 1929, pp. 329-338.

Left: Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Editions Cahiers d'Art, Paris, 1928., Langmead 174. Right: J. J. P. Oud, Henry Russell-Hitchcock, Editions Cahiers d'Art, Paris, 1931.

A very fascinating write-up on the genesis of the publication of the above Frank Lloyd Wright and its introduction, written by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, can be found in Anthony Alofsin's extremely well-researched Wright in New York. Suffice it to say that Hitchcock's negativity towards Wright was equally balanced by Doug Haskell's inclusivity. Hitchcock also wrote an into in 1931 for one of his "New Pioneers," J. J. P. Oud, for the same French publisher, which was much more suited to his by then ingrained International Style interests and his soon-to-be inclusion in MOMA's 1932 Modern Architecture exhibition. (Alofsin, pp. 188-193). (Author's note: Douglas Haskell published "Organic Architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright" in Creative Art, November 1928, pp. 51-57. Langmead 175).

The April issue ended with Lewis Mumford's "Frank Lloyd Wright and the New Pioneers" in the Architect's Library section, which reviewed Henry-Russell Hitchcock's above compendium, Frank Lloyd Wright, published in France the previous year by Editions Cahiers d'Art. Mumford's thoughtful three-page review detailed his differences with Hitchcock on their perspectives on Wright's importance to the evolution of modern architecture. In a brief excerpt, he wrote,

"I find myself a little puzzled by Mr. Hitchcock's summary of

Mr. Wright's career, for the critic's admiration is so thoroughly

counterbalanced by his disapproval of the central motives in Mr. Wright's work

that one is driven to conclude that either Mr. Wright is not the great master

Mr. Hitchcock says he is, or the critic's feelings do not square with his

abstract principles." (Ibid., pp. 414-416.)

After the review appeared, Hitchcock wrote to Mumford, "We have more in common than you are willing to admit - our chief difference being that it pleases me to look at a warming - if that is the word I want - or enriching of architecture - au de la de Le Corbusier and not before him chez Wright." (Henry-Russell Hitchcock to Lewis Mumford, June 21, 1929, in Lewis Mumford and American Modernism, Robert Wojtowicz, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 58.).

Portfolio of Current Architecture, Church of St. Anthony, Basel, Switzerland, Karl Moser, Architect, Architectural Record, May 1929, pp. 435-443.

Karl Moser's Church of St. Anthony in Basel, Switzerland, made the pages of Kocher's magazine in the May 1929 issue. In 1919, Neutra had accompanied Moser's class on a sketching expedition, honing his drawing skills of antique furniture and architectural interiors. His son, Werner, and wife, Sylva, had stayed with the Schindlers at Kings Road in 1924 on their way to Taliesin, where they met the Neutras and the Tsuchiuras.

(From Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture, Thomas S. Hines, Oxford University Press, New York, 1982, pp. 52-3.). (See also my "Taliesin Class of 1924"). (Author's note: Frank Lloyd Wright's former apprentice and Walter Burley Griffin partner Barry Byrne and sculptor friend Alfonso Iannelli collaborated on Christ the King Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Byrne's model of Christ the King Church in Cork, Ireland, which were both also published in this issue. Ibid., pp. 461-466. See much more on Byrne and Iannelli in my "Irving Gill, Homer Laughlin and the Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Los Angeles, Part II, 1911-1916").

Proposed Drive-In Market, Los Angeles, Richard J. Neutra, Architect, Architectural Record, June 1929, p. 606. (Author's note: Neutra's "Proposed Drive-In Market" was published again the following year in Paul Frankl's Form and Re-Form, seen later herein.)

Palm Drive-In Market, Los Angeles, J. Byron Severance, Architect, and Mesa Vernon Drive-In Market by George J. Adams, Architect, Ibid., p. 603.

Photos by Willard D. Morgan.

The June 1929 issue of the Record included an article by staff on "Store Buildings," in which Kocher used a rendering by Neutra on a "Proposed Drive-In Market" and two images of drive-in markets by Neutra's then photographer, Willard D. Morgan. Also included was the page below of a shop building (The El Paseo Building) in Carmel by Blaine & Olsen, the same firm that had designed the Kocher Building for A. Lawrence Kocher's doctor brother, Rudolph, across the street in Carmel the previous year. They also designed and built the Hotel La Ribera for Rudolph Kocher later that same year. (Author's note: Pauline Schindler and Edward Weston were witnesses to Rudolph Kocher's projects being built during their overlapping stays in Carmel. See, for example, my "Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism" (PGS).

Left:A Shop Building for L. C. Merrill, Carmel, Blaine & Olsen, Architects, Architectural Record, June 1929, p. 608. Top Right: Hotel La Ribera, Carmel, 1929, for Dr. Rudolph A. Kocher, Blaine and Olsen, Architects. Bottom Right: Kocher Building, Carmel, 1928, for Dr. Rudolph A. Kocher.

Left:A Shop Building for L. C. Merrill, Carmel, Blaine & Olsen, Architects, Architectural Record, June 1929, p. 608. Top Right: Hotel La Ribera, Carmel, 1929, for Dr. Rudolph A. Kocher, Blaine and Olsen, Architects. Bottom Right: Kocher Building, Carmel, 1928, for Dr. Rudolph A. Kocher.The July issue again published Hitchcock's monthly review of "Foreign Periodicals," this month featuring Germany. It was followed by a book review by Douglas Haskell of German photographer Karl Blossfeldt's Uformen der Kunst. His glowing review compared Blossfeldt's enlargements of natural objects with art and architecture. An excerpt reads,

"But the present book is not so pedantic. Its quality is one

of infinite allusion. If its pictures seem to show that beautiful form in

Nature is a result of a sort of natural engineering, that is largely because,

with the present-day passion for purity and selection, the author has always

chosen the single instance in its perfect clean example. But the geometry gets

covered with flesh, and then pedantic generalizations get lost and transcended."

Uformen der Kunst, review by Douglas Haskell, Architectural Record, July 1929, pp. 87-88.

The issue with "Notes and Comments" included a three-page essay from Frank Lloyd Wright titled "Surface and Mass - Again!" It was written in late April 1929 while Wright was in Chandler, Arizona, consulting on the Arizona Biltmore project, which comprised most of the month's issue. (see below).

Arizona Biltmore Hotel, Phoenix, Arizona, Albert Chase McArthur, Architect, Ibid., July 1929, pp. 19-55. The project was also published in the December 1929 issue of Architectural Forum, pp. 139-141.

After the publication of the July issue, Frank Lloyd Wright wrote a lengthy letter to Werner Moser referencing his father's church-tower published in the May 1929 issue of Architectural Record, seen earlier herein. In an excerpt, Wright wrote,

"Somewhere I saw a church-tower I admired very much.. Yes, at Basel, Professor K. Moser. Am I wrong in believing that your father did it? ... Look at the Architectural Record for July. The Arizona Biltmore for one thing, and at the back, among the Notes and Comments, my first comeback to all this "Surface and Mass" business of Corbusier et al. You ought to enjoy it. The war is on I guess." (From Frank Lloyd Wright to Werner Moser, July 25, 1929 in Frank Lloyd Wright, Letters to Architects, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Cal. State University Press, Fresno, 1995, p. 76.).

About the same time, Wright facetiously wrote to the Neutras, who also spent most of 1924 at Taliesin with Werner and Sylva Moser and Kameki and Nobu Tsuchiura,

"My dear Richard, Writing Rudolph brings you to mind, and here's wondering how your garden grows. I've heard some pessimistic reports of your efforts and more of your state of mind. Lloyd said you were engaged upon on a book [Amerika], "History of American Architecture," I believe, in which you proposed to leave my name out entirely. I think this is a good idea. It would make room for a lot of others that otherwise might not have enough. And from someone - I forget who - that you were importing foreign draughtsmen from Corbusier et al. and with them starting a school of new-thought in Architecture in Hollywood, which is a vigorous enterprise and likely to be successful, if the crowd can be kept well out in front. I guess you can keep them there long enough to let the show go on to a logical conclusion or a natural end. But there is better and almost good. The boys tell me you are building a building in steel for residence. - which is really good news. Ideas like that one are what this fool country needs to learn from Corbusier, Stevens, Oud and Gropius. I am glad you are the one to "teach" them." (FLW to Richard Neutra, August 1929, Richard Neutra, Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932," edited by Dione Neutra, Southern Illinois University Press, 1986, p. 178).

Despite expecting to be left out of Neutra's second book, images of his work appeared 13 times, almost as many as his former draftsman in Louis Sullivan's office, Irving Gill, who was represented with 16 illustrations. In a somewhat apologetic second letter after Neutra's response, Wright repeated his earlier message to Werner Moser, pointing out Lewis Mumford's "Frank Lloyd Wright and the New Pioneers" in the April issue of the Record and Wright's article "Surface and Mass - Again!" (Ibid., p. 179).

In Wright's "war" of words with Corbusier, he was also trying to convert Hitchcock and Haskell to his way of thinking. As an example:

"At the moment she [nature] has her eye on Douglas Haskell and Russell

Hitchcock. Here come, eventually, valuable critics? Yet, by way of the former,

last November, I learn that by ‘weight’' I am satisfactorily betrayed into the

long grasp of Tradition. (Wright was responding to Douglas Haskell, "Organic Architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright," Creative Art 3, (November 1928): li-lvii. and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, "Modern Architecture I: Traditionalist and the New Tradition," Architectural Record 63 (April 1928), 337-49).

Well—insofar as Architecture may not be divested of

the weight of organic nature, I plead guilty,—the trees are guilty likewise.

Useless weight and ornament are sins I have sinned. Sometimes for a holiday.

Sometimes betrayed by a happy disposition. Week days I seek lightness,

toughness, sheerness, preferring them. Week ends I fall from grace. Has

machinery already made exuberance a sin? poverty a virtue?

Meantime,—my

critics,—although a pupil of Louis Sullivan, never have I been his disciple. He

has himself gratefully acknowledged this publicly. Had I been his disciple I

should have envied him and in the end have betrayed him." ("Surface and Mass - Again," Frank Lloyd Wright, Ibid., pp. 92-94).

The August 1929 issue continued the magazine's steady evolution towards modernism, leading off with a massive piece by Schindler and Neutra's fellow Viennese architect-designer Joseph Urban's assistant, Shepard Vogelgesang, on the restoration of the "Central Park Casino, Joseph Urban, Architect." Le Corbusier also contributed a five-page article to the August issue in response to Kocher's May 1928 request. In soliciting the magazine's first article by Le Corbusier, Kocher expressed optimism about its reception. "In this land of standardized products and mass production, there should be a universal acceptance of your arguments." Kocher even proposed the title, "Architecture, the Expression of the Materials and Methods of our Times." Corbusier's article introduced American readers to his recent works, Centrosoyus in Moscow, his Plan Voisin in Paris, Villa Stein, and Weissenhof. (Bacon, pp. 19, 327. Letter, A. Lawrence Kocher to Le Corbusier, May 8, 1928, Foundation Le Corbusier. Letter Le Corbusier to "Messieurs, the Architectural Record, FLC).

Corbusier, second from left, Albert Frey in the back, and Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret to the right. Rosa, p. 19.

Left: "Two Houses at Stuttgart. Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Architectural Record, August 1929, pp. 123-128. Right: Zwei Wohnhauser (Two Houses) von Le Corbusier und Pierre Jeannaret by Alfred Roth, Akadermischer Verlag Dr. Fr. Wedekind, Stuttgart, 1927.

"[The above] book showcases two houses designed by Le Corbusier together with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. It was published in 1927 for the exhibition of the Weissenhof Estate organized by the Deutscher Werkbund in Stuttgart, and was authored by Swiss architect Alfred Roth who at that time worked for Le Corbusier and Jeanneret. Zwei Wohnhäuser includes Le Corbusier’s “Five Points to a New Architecture” and a foreword by Hans Hildebrandt. It has 48 pages measuring 29.5×21 cm and was published by Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fr. Wedekind & Co., Stuttgart. For the fiftieth anniversary in 1977, Karl Krämer Verlag issued a facsimile edition, with a foreword by Roth, “Memories of the Construction of the Weissenhof Estate.” (Fonts in Use).

The author/editor of the above book, Alfred Roth, was also a close friend of Albert Frey, whose time in Corbusier's atelier overlapped. Roth was recently out of college and working for Karl Moser when Moser recommended that he work on Le Corbusier's League of Nations design competition entry. based on his professor Karl Moser's personal recommendation. After completion of the League entry, while Roth was next working as a field supervisor on Corbusier's houses at the Weissenhof Estate and organizing the above book, Frey was working for Leuenberger & Fluckiger in Zurich. Frey would also eventually join Le Corbusier's Atelier in October 1928, where he would have definitely viewed the above book. He would soon be collaborating on the Villa Savoye and many other projects.

(Gut-Frey) House in Zurich, Switzerland, designed by Albert Frey, 1933, Architectural Record, July 1936, pp. 35-40.

Zwei Wohnhauser by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jenneret through Alfred Roth, Verlag Dr. Fr. Wedekind & Co., Stuttgart, 1927, pp. 10-11.

Roth's above illustrations of Corbusier and Jeanneret's design elements for the Weissenhof Estate houses also appear in the below Bau und Wohnung and obviously inspired Kocher & Frey's 1930 design of their Aluminaire House, which will be described in much more detail below. While the men were both seen as the face of the practice, Frey held the primary design role, while Kocher provided mentoring and final analysis. (Rosa, p.

Bau und Wohnung, F. Wedekind, Stuttgart, 1927. Front cover and pp. 29 &34. From Hathi Trust.

The August 1929 issue of the Record continued with a book review, again by Shepard Vogelgesang, of the German language Glas im Bau und als Gebrauchsgegenstand by Arthur Korn. It seems plausible that Hitchcock or Kocher took advantage of German-speaking contributors to translate foreign books of interest. Vogelgesang gave an enthusiastic review using some photos of the author's work to illustrate, and ended with,

"A book exhibiting cooperation on such a geographic and

industrial scale as does Glas comes as an inspiration; it cannot be regarded as

illustrating an arbitrary whim but must be held as an index of a powerful

current in design." (The Architect's Library, Book Reviews, Glas im Bau, Shepard Vogelgesang, Ibid., August 1929, pp. 190-1. Vogelgesang also reviewed "Architect and Engineer" in the September 1929 issue of Architectural Forum, pp. 373-386).

Internationale Architektur Bahausbucher 1 by Walter Gropius, (second edition), Albert Langen Verlag, Munchen, 1927.

Hitchcock also reviewed the second edition of Internationale Architektur by Walter Gropius. The book included many projects, built and unbuilt, since the publication of the first edition in 1925, including Neutra's design for a skyscraper first published in his Wie Baut Amerika? and Hitchcock's review of the same in the June 1928 issue. While Hitchcock lauded the work of Gropius and the Bauhaus, Corbusier, J. J. P. Oud, Mort Stam, Ernst May, and Hannes Meyer and Hans Witwer's design for the Palace of the League of Nations, he also avered, "The present second edition makes it again possible to obtain

what is perhaps the finest epitome of modern architecture and provides for the

inclusion of certain work that has been executed since the book first appeared." (Internationale Architektur, Walter Gropius, Bauhausbucher 1, second edition, 1927, Architectural Record, August 1929, p. 191.).

Left: "The Architect and the Industrial Arts" exhibition catalogue cover, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 12 to September 2, 1929. Right: "Apartment House Loggia" designed by Raymond Hood, Ibid.

Left: "The Architect and the Industrial Arts" exhibition poster. Right: Entrance to the "The Architect and the Industrial Arts" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ibid.

Before the Museum of Modern Art had its first exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum of Art staged a major exhibition of modern interior design work with the above catalog featuring 25 mentions by New York Architectural League inner circle members Raymond Hood, 45 by Joseph Urban, and 88 by Ely Jacques Kahn. No mentions were made of Paul Frankl, Kem Weber, William Lescaze, or William Kiesler, thus indicating a rivalry of sorts between the Architectural League and AUDAC, formed by Frankl, Lescaze, and others the previous year.

A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record to K. Lonberg-Holm, September 4, 1929.

Kocher responded to Knud Lonberg-Holm

(see above) regarding his proposed article on "Architecture and Organized Space" just about the same time he and Neutra were becoming American delegates for CIAM under President Karl Moser.

(see below). Knud also submitted an article for publication entitled "Architecture in the Industrial Age," which Kocher rejected because "it was far too radical for the professional architectural press." Kocher instead hired Lonberg-Holm, and they would end up collaborating on many technical articles published in the

Record over the next six years and with Lonberg-Holm being listed as a contributing editor on the masthead.

(Strum, S.

(2012). Informational Architectures of the SSA and Knud Lönberg-Holm. In:

Williams, K. (eds) Architecture, Systems Research and Computational Sciences.

Nexus Network Journal, vol 14,1, p. 38. Author's note: In the late 1930s F. W.

Dodge, Architectural Record's parent company, transferred Lonberg-Holm to head

its Sweet's Catalog Service, where he collaborated with Czech graphic designer Ladislav Sutnar on many projects.)

Dwellings for Lowest Income, International Congress for New Building, Zurich, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1929, p. 45. (Author's note: For a good description of Neutra starting an American chapter of CIAM, see The Organic View of Design, Harwell Harris Oral History Interview.) (For Albert Frey's extensive CIAM connections, see my "Albert Frey: The Formative Years, 1925-1930").

R. M. Schindler portrait by Edward Weston, ca. 1927-8. Edward Weston Collection, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

Edward Weston took the above portrait of R. M. Schindler shortly after taking the below photos of the Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach on August 2, 1927.

A. Lawrence Kocher to R. M. Schindler, July 25, 1929. Courtesy Schindler Collection, UC-Santa Barbara. Neue Villen, edited by Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1929.

Architectural Record editor A. Lawrence Kocher was

indirectly responsible for developing the careers of Richard Neutra and R. M.

Schindler due to his naming Henry-Russell Hitchcock contributing editor in 1928.

Hitchcock's "discovery" of Neutra in European periodicals led to the

publication by Kocher of Schindler's How and Lovell Houses. He further promoted

Schindler's work by lending pictures of the same to architectural critic Lewis

Mumford for publication in Europe, as can be seen in the above July 1929 letter

to Schindler. The work soon appeared in Neue Villen, published by Julius

Hoffmann in Stuttgart, the same publisher of Neutra's 1927 Wie Baut Amerika?

Lewis Mumford, ca. 1931-2, Guggenheim Fellowship application photo. Photographer unknown.