(Click on images to enlarge)

Esther McCoy is acknowledged by most fans of our rich Southern California architectural heritage as the true pioneer in keeping the flame of recognition alive for numerous Southland architects, from former

Louis Sullivan apprentice

Irving Gill to the

Case Study House Program participants. She will also forever be remembered as a forerunner in the preservationist movement for those architects' now iconic structures. Her papers are well-cataloged and safely housed at the

Smithsonian Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. and have recently been digitized. I highly recommend spending an afternoon or two browsing her extensive archive. Also must reading is her

oral history conducted in 1987 by Joseph Giovannini two years before her passing to get a sense of her intriguing life and letters which led to her highly successful career as a chronicler of Southern California's modernist architectural history.

(A synopsis of McCoy's life can be read at Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century by Susan Ware, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, 2004. See also Being There: Esther McCoy, the Accidental Architectural Historian by Susan Morgan for a preview of her biography in progress.).

Born in 1904 in Horatio, Arkansas, Esther McCoy was raised in Kansas. She attended the Central College for Women, a preparatory school in Lexington, Missouri, prior to a college career which took her from Baker University, to the University of Arkansas, then to Washington University, and finally the University of Michigan. She left the University of Michigan in 1925, and by 1926 was living in New York City and embarking on a writing career. In 1932 McCoy was diagnosed with pneumonia and headed West for Los Angeles to recover. She purchased a bungalow in the Ocean Park section of Santa Monica in the late 1930s, where she lived for the remainder of her life, although she traveled widely. During World War II, McCoy worked as a draftsman for R.M. Schindler after being discouraged from applying to USC

's architecture school due to her age and sex. After a long and varied writing and teaching career, she died in December 1989. (Excerpted from Wikipedia).

Following is a more or less chronological ramble through the highlights of her fascinating career in which she brought alive the maturation of modernism California-style to Southern Californians and the rest of the world.

Esther McCoy ca. 1924 from Theodore Dreiser: Letters to Women, New Letters: Volume II edited by Thomas Riggio, University of Illinois Press, 2009, p. 308. Courtesy Theodore Dreiser Papers, Penn Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

While she was still in school at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, McCoy sent t

he above photo to her idol Theodore Dreiser a few years after he had returned from a three-year sojourn in Los Angeles. (For more on Dreiser and his future wife Helen Richardson's time in Los Angeles see my "Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole and Their Dramatic Circles."). McCoy would soon thereafter move to New York where she first made ends meet by proofreading manuscripts for publishers, writing book reviews and performing research for Dreiser. McCoy reminisced fondly of her early days in New York in her "Patchin Place: A Memoir" which was published by Ben Sonnenberg in the Fall 1985 issue of

his highly respected literary Journal Grand Street. In the article McCoy relates that her first work for Dreiser was researching a piece he was doing on one of her later mentor Pauline Schindler's idols Emma Goldman. She also spoke fondly of her neighbors which included John Cowper Powys and his long time companion Phyllis Playter and E. E. Cummings. (For much more on Goldman and Powys see my "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School").

R. M. Schindler and Theodore Dreiser viewing the floor plan of the 1945 Bethlehem Baptist Church, 4901 Compton Ave., Los Angeles, 1944, Thomas Jefferson Art Gallery, Santa Monica, 1945. Photographer unknown. (McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art)

Dreiser and Helen Richardson would later become neighbors to the Schindlers on Kings Road (see above and below) from 1941 until his December 1945 passing. Through the largess of Pauline Schindler McCoy would become a draftsman for RMS (see above) from 1944 until 1947 which directly led to her illustrious career as an architectural historian. A year before her death McCoy would pen the poignant "The Death of Dreiser" referencing the Schindlers' role in her life. This touching piece was also published in Grand Street (see two below).

Helen Richardson and Theodore Dreiser, 1015 N. Kings Road, West Hollywood, ca. 1944. Courtesy Theodore Dreiser Papers, Penn Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

.jpg)

McCoy selected Dreiser's poem "The Road I Came" for reading at his January 1946 funeral ceremony at Forest Lawn Cemetery with pall-bearer Charlie Chaplin (see above) doing the honors.

Los Angeles Times literary critic

Paul Jordan-Smith (see upper left below) was so struck by the poem that he adopted the title for his 1960 autobiography.

(For more on Paul Jordan-Smith, Dr. Gerson and Will Durant see my "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School." For more on Charlie Chaplin and his connections to the Weston-Mather-Schindler circles see my "Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole and Their Dramatic Circles." For more on Dan James and his parents' iconic Carmel Highlands Residence designed by Charles Greene where Chaplin stayed in the 1930s see my "Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence." Author's note: A client of Schindler, Leo Gallagher was also a close friend of Pauline's and the Lovells. While Lovell was studying law under Gallagher they traveled to Moscow together in 1931. Sometime in the 1940s McCoy wrote a lengthy article about Gallagher and his defense of the artists whose work was destroyed in the John Reed Club Red Squad Raid of February 1933 shortly after she arrived in Los Angeles. For more on the Red Squad Raid see my "Richard Neutra and the California Art Club").

Dreiser Memorial, Severence Club, January 1946. Paul Jordan-Smith [speaker], Dr. T. Perceval Gerson [President], Dr. Will Durant [speaker], John Moore [speaker], Marcia Masters [read Dreiser's poetry], and Helen Richardson Dreiser. (For more on Dreiser and Helen Richardson's time in Los Angeles during 1920-21 while she was trying to break into the movie business see my "Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole and Their Dramatic Circles.").

Esther McCoy, Helen Dreiser and Berkeley Tobey, Santa Monica Pier, September 5, 1949, a few years after the death of McCoy lifelong friend, mentor and Schindler neighbor, Theodore Dreiser, she so touchingly wrote about in the above issue of Grand Street. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Theodore Dreiser Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

McCoy's background as a fiction writer (

The New Yorker (see below),

Harper's Bazaar,

Vanity Fair and quarterly literary journals such as

California Quarterly and

Grand Street), world traveler, involvement with novelist and journalist

Theodore Dreiser and employment as a draftsman for

R. M. Schindler evolved her uniqueness in turning an architectural phrase in a way that deeply engages the layperson. In re-evaluating the uniqueness and importance of McCoy's work in an essay written shortly before her death,

Robert Venturi and

Denise Scott Brown opined,

"In Five California Architects in 1961 and in The Second Generation in 1984, Esther McCoy established what might be considered a new genre, relating social history and architectural criticism and linking them to a novelist's observation about character: she produced architectural criticism with a human face." ("Re-Evaluation: Esther McCoy and the Second Generation," Progressive Architecture, February 1990, pp. 118-9).

Her frequent articles in the

Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, Mademoiselle's Living (see below, later

Living for Young Home Makers), Sunset and many other mass market publications illustrated and defined the work of modernist architects and architecture for a broad audience. Her collaboration with the best architectural photographers Los Angeles had to offer in

Julius Shulman,

Marvin Rand and others guaranteed her work's immortality.

Esther McCoy posing in the George P. Turner Residence, Flintridge, 1947 in one of her earliest architecture articles "Plans for Young Houses: The Turners' own five-year plan," Mademoiselle's Living, Winter 1948. Maynard Parker Job No. 2412-18 from the Parker Archive, Huntington Library.

McCoy was also respected in the academic community for her work as a contributing editor for

Arts & Architecture, Progressive Architecture, Zodiac, Lotus, Global Architecture, Domus, Perspecta, Journal of Architectural Historians, and many others. Following is a chronological walk down memory lane with a selection of some of her better known architectural exhibition catalogs and monographs.

McCoy, Esther, "Schindler, Space Architect,", Direction, Vol. 8, No. 1, Fall, 1945. Cover design by Paul Rand. From Paul Rand by Steven Haller, Phaidon, 1999, p. 31. (From my collection).

McCoy began her career as an architectural historian with a piece on her employer titled "Schindler, Space Architect" which was published in the Fall 1945 issue of

Direction (see above),

"a cultural magazine with a left-wing slant and anti-fascist bias" published by

Marguerite Tjader Harris, the daughter of a wealthy munitions manufacturer.

(Haller, p. 26). From 1937 until 1945 Mrs. Harris edited Direction, the left-wing journal of the arts she founded with the support of Dreiser. In 1944 Harris (see below), who had also carried on a long-time intimate relationship with architect Le Corbusier, and her son moved to Los Angeles where she became, like McCoy, one in a long succession of Dreiser editorial assistants.

Theodore Dreiser, Helen Richardson, Marguerite Tjader Haris and son at the Dreiser's Kings Road home, 1944. Photographer unknown (Esther McCoy?). Courtesy Theodore Dreiser Papers, Penn Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Strongly attracted to Dreiser as was McCoy, Harris had an

off and on intimate relationship with him from the time of their 1928 meeting until 1944 when he finally married Helen Patges Richardson, his companion of almost 30 years. In addition to typing and editing drafts of his work she acted as a sort of 'spiritual advisor' to Dreiser while he completed his penultimate novel The Bulwark, published posthumously in 1946. Harris is also likely the model for the title character of 'Lucia', one of the fictional sketches in Dreiser's A Gallery of Women, published in 1929. (For much more on the Richardson-Dreiser relationship and his Gallery of Women see my "Edward Weston, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole and Their Dramatic Circles"). Interestingly, McCoy's

Direction piece on her employer and Dreiser's Kings Road neighbor Schindler, coincided with the last of

Paul Rand's 23

distinctive covers for the prestigious publication over a seven-year period.

(Haller, pp. 26-31).

McCoy, Esther, "The Important House", The New Yorker, April 17, 1948, pp. 60-64.) (From my collection).

McCoy was just beginning her architectural writings when she penned

"The Important House" for the April 17, 1948 issue of

The New Yorker. It is a humorous, fictional account of a Shulmanesque architectural photographer staging a modern house for an important photo shoot. McCoy had begun collaborating with

Julius Shulman for the first time a few months earlier for the article, "A Servantless House Meets Three Needs" on R. M. Schindler's Presburger House for the November 23, 1947 issue of the

Los Angeles Times Home Magazine.

The New Yorker article is important as it is a fine early example of McCoy's ability to harness her considerable literary talents to her new-found profession as an architectural critic and soon-to-be historian and must have been a big confidence booster for her. The

Times article is also significant because it initiated a 40-year collaboration between the two Southern California modernist icons which resulted in close to 200 McCoy articles with Shulman photos appearing in a global array of publications, not to mention Shulman's lion's share of the images in the books discussed below. My related article,

A Case Study in the Mechanics of Fame: Buff, Straub & Hensman, Julius Shulman, Esther McCoy and Case Study House No. 20, is a good illustration of the fame-making capability of this dynamic duo. Every architect worth their salt in the 1950s and 60s knew that McCoy's and Shulman's skills and close association with

Arts & Architecture editor John Entenza could open many doors for them. Their joint work for Harwell Hamilton Harris disciple Gordon Drake has similarly helped to keep his legend alive.

(See also The Post-War Publicity Partnership of Julius Shulman and Gordon Drake: Gordon Drake: An Annotated & Illustrated Bibliography).

McCoy, Esther, "The Cape," in The Best American Short Stories 1950 edited by Martha Foley, Houghton-Mifflin. From Royal Books.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, while still transitioning into her architectural historian career, McCoy continued to write prize-winning fiction evidenced by her short story, "The Cape" being published in the October 1949 issue of

Harper's Bazaar and then anthologized in

Martha Foley's highly prestigious

The Best American Short Stories 1950 (see above)

. To be anointed with publication in either the annual

O.Henry Prize Stories anthology or

The Best American Short Stories anthology, started in 1915 under Edward O'Brien and continued by Foley from 1941 through 1977, was a major highlight of any writer's career and must have given McCoy's ego a huge boost.

McCoy and husband Berkeley Tobey spent time in Ensenada, Mexico in the late 1940s and for the better parts of 1951-52 McCoy was engrossed in serious research in Mexico City, Cuernevaca and elsewhere. Her lifetime love affair with Mexico, emboldened by her fortuitous meeting of Clara Porset, would be shared with her favorite photographer-collaborator Julius Shulman over the next decades. During her trips she collected source material for future articles on Mexican art and architecture and exhibitions on noted architect Juan O'Gorman and noted architect-structural engineer Felix Candela (see exhibition discussions later below).

Mexico's Modern Architecture by I. E. Myers, Architectural Book Publishing Co., New York, 1952. Cover photo by Guillermo Zamora of a house by Nicolas Mariscal. (From my collection).

Also deeply fascinated with Mexico and its burgeoning modernist architectural scene, Irving E. Myers began work on his groundbreaking 1952 publication Mexico's Modern Architecture (see above) apparently sometime in the late 1940s. McCoy perhaps heard of Myers' book project through mutual connection Richard Neutra whom Myers had asked to write his insightful introduction. Other possible mutual connections with Myers could have been furniture designer and potential business partner Clara Porset, her 1951 photographer-collaborator Elizabeth Timberman or any of the architects Myers had been interviewing during his research. One of those architects was

Enrique Yanez who was also Chief of the Department of Architecture of the National Institute of Fine Arts, under whose auspices Myers was granted a fellowship to fund his book research.

Irving E. Myers, ca. 1951. Photographer unknown. From back dust jacket flap, Mexico's Modern Architecture by Irving E. Myers, Architectural Book Publishing Co., New York, 1952.

Having attended sculpture and architectural classes at USC before WW II, the decorated Myers was recuperating from serious war wounds in Mexico with his wife and infant son. He immediately became so impressed by the exciting modernist architectural scene there that he was compelled to plunge headlong into the compilation this seminal book. Neutra's considerable Mexican connections possibly opened many doors for Myers which he gratefully acknowledged in the book's front matter. For example possibly under Yanez's largess, Neutra lectured in Hall of the Palacio de las

Bellas Artes in Mexico City in early 1938 at the invitation of the Secretary of Education of

Mexico and the Mexican Association of Architects. The

L.A. Times reported on Nuetra's visit,

"Representatives of the university, of the artists association, and of the building professions expressed the opinion that Los Angeles is exercising and will continue to exert the most significant influence on Mexican building development and that mutual understanding may greatly benefit both cities." ("Architectural Influence Told," Los Angeles Times, January 16, 1938, p. V-1).

The New Architecture in Mexico by Esther and Ernest Born, Architectural Record, 1937.

(Author's note: Two years prior to Neutra Ernest and Esther Born made a seminal visit to Mexico City to capture on film "The New Architecture

in Mexico." This resulted in a special issue in

Architectural Record and the book of the same name being published in 1937 (see above).

(Ibid and Born, Esther and Ernest, "The New Architecture in Mexico," Architectural Record, April 1937, pp. 1-86).)

In Myers' book foreword, his patron Enrique Yanez wrote,

"The National Institute of Fine Arts of Mexico, in the pursuit of one of its aims, that of making known to the world the artistic works of our nation, provided Mr. Myers with a fellowship and placed at his disposal the graphic materials of the 1950 exhibit of Contemporary Mexican Architecture arranged by this Institute, which were necessary for the completion of this book. Mr. Myers, a young North American, veteran of World War II in which he was severely wounded, arrived in Mexico to convalesce, at an opportune time. His impressions of Mexico impelled him to undertake the writing of this book, to acquaint professionals and laymen throughout the world with our modern architectural movement. His deep affection for Mexico and immediate understanding of our problems have produced a book we are proud to acknowledge. ... For these reasons Mr. Myers book, into which he has put intelligence, understanding and tireless effort, has great importance for Mexican architects as well as for the world. In making our works known to professional circles abroad, this book has made possible a wider perspective by which to judge our own development and to evaluate what has been accomplished. This will lead to the recognition of our capacities and to the inevitable conclusion that it is necessary, through government action, to project our efforts toward united tasks of genuine social benefit."

After returning to the U.S. after publication of his book, Myers became a noted architectural publicist, historian, design and research consultant, and foreign correspondent for European and Mexican architectural journals opening offices in the Architect's Building in Los Angeles and New York (see discussion later below).

("Office Opened by Author-Designer," Los Angeles Times, May 13, 1956, p. VI-8. Many thanks to architect and noted historian Pierluigi Serraino for bringing Myers to my attention. His book had been sitting on my library shelf for years without me reaalizing its true significance.).

Clara Porset and Alfonso Rojas with jig for one of her chairs, 1951. Photo by Elizabeth Timberman. Courtesy Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 31).

While in Mexico in the spring of 1951 McCoy was also learning of the exciting happenings in Mexican modern architecture and visited furniture designer

Clara Porset. This is also possibly when she caught wind of Myers' book project. McCoy returned to the U.S. in May to excitedly share her photos of Mexican modernist architecture and Porset's furniture with

Arts & Architecture editor and publisher John Entenza. She also by then had in her possession a copy of Myers' patron Enrique Yanez's

18 Residencias de Arquitectos Mexicanos - 18 Homes of Mexican Architects published earlier that year (see later below).

Most likely in a concerted effort to "scoop" Myers and be the among the first to introduce Mexican Modernism to the U.S., McCoy easily convinced Entenza to run articles on Porset's remarkable furniture designs and some of the architecture Myers was planning to include in his book. Possibly unbeknownst to McCoy, Entenza had run a brief piece on Mexican modern architecture in 1940 in conjunction with the excitement surrounding Diego Rivera's presence working on his tour de force mural "

Pan American Unity" under the auspices of the Expo's "

Art in Action" program.

(Author's note: Perhaps the introduction to Porset was provided by Pauline Schindler who had met Porset's husband Xavier Guerrero while he was shepherding a major exhibition of Mexican art and craftwork in Los Angeles in the summer and fall of 1922. Then Edward Weston lover Tina Modotti was assisting her future lover Guerrero in the marketing of the exhibition and Pauline aided in publishing Modotti's review of the show in Holly Leaves. Guerrero had most likely visited the Schindler's Kings Road house during his time in Los Angeles. For more on this see my "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association" and "Schindler-Weston-Franz Geritz-Arthur Millier Connections").

Chairs by Clara Porset in the patio of a house designed by architect Mario Pani. Photo by Lola Alvarez Bravo. From Mexico's Modern Architecture by Irving E. Myers, Architectural Book Publishing Co., New York, 1952, p. 93 and McCoy, Esther, "Chairs by Clara Porset," Arts & Architecture, July, 1951, pp. 34-5. Coincidentally the same issue contained a two-page review of the Girsberger publication Richard Neutra edited by Willy Boesiger by Jaqueline Tyrwhitt.

McCoy's July 1951

Arts & Architecture piece on Porset was illustrated with the same

Lola Avarez Bravo photos Myers was planning to use in his book (see above for example). McCoy was assisted on this article by her

Life Magazine photographer friend and colleague

Elizabeth Timberman, then apparently living in Mexico who provided McCoy numerous supplemental photos of

Porset and her work. Since editor John Entenza did not pay for articles or photography, to save her time in preparing the article McCoy requested from Porset a 400 word statement, photos and captions to use alongside her brief introduction.

The

McCoy-Porset correspondence seemingly indicates that as early as the spring of 1951, McCoy had designs on partnering with Porset on the marketing of her modern furniture in the U.S.. It is not clear to me whether McCoy was knowledgeable of Artek-Pascoe's 1946 efforts to exhibit and sell Porset's furniture on the East Coast as their correspondence is silent on this. For most of 1951 McCoy eagerly and exhaustively investigated ways and means to manufacture and distribute Porset's now iconic work in the U.S..

McCoy met with her former employer R. M. Schindler and his cabinet maker, Charles Eames and his erstwhile furniture business partner Entenza, representatives from Herman Miller and Modern Color,

Frank Brothers Furniture Co.,

Carrol Sagar and many others. She also brought to bear on the deal the marketing expertise of her photographer-collaborator Julius Shulman. Shulman proudly photographed Porset's chairs in the context of his brand new Rafael Soriano-designed house (see below). In one of her letters to McCoy Porset remarked about the rapidity McCoy was pushing to get the July and August 1951 articles to press.

In her introduction of Porset in her July 1951

A&A article McCoy avered that Porset had assembled the material for the recent exhibition of modern Mexican architecture at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City that Yanez mentioned in his foreword to Myers' book (see earlier above). If this was indeed the case it would seem likely that Porset and Myers would have collaborated in some fashion since Yanez provided Myers a fellowship and the graphic materials used in the exhibition for the preparation of his book. This is further evidenced by Myers arranging the traveling of the same, or a similar exhibition under the auspices of the Ministry of Fine Arts in conjunction with the 1956 A.I.A. national convention in Los Angeles discussed later below. Since neither Myers' book "Acknowledgments" nor Yanez's "Foreword" make any mention of Porset many questions remain unanswered.

Entenza and McCoy continued their "scoop" with an August 1951 issue devoted entirely to modern architecture in Mexico. Besides the article "Jardines del Pedregal de San Angel" and a lengthy, informative essay "Architecture in Mexico" describing the current architectural scene, McCoy selected eight of the 70 architects Myers featured in his book, including Luis Barragan, Max Cetto, Enrique Del Moral, Luis Rivadeneyra, Jaime Lopez Bermudez, Victor De La Lama, and Ramon Torres Martinez to feature in the issue. She requested photos, captions and statements from a few of these same architects while also using Timberman as an intermediary with the others (see

Max Cetto-Esther McCoy correspondence for example). These July and August articles were McCoy's first ever to be published in

Arts & Architecture and presciently prompted her future Graham Foundation benefactor Entenza to name her to the magazine's editorial advisory board a couple months later.

18 Residencias de Arquitectos Mexicanos - 18 Homes of Mexican Architects by Enrique Yanez, Ediciones Mexicanas, Mexico City, 1951. Cover photo of architect Enrique Del Moral's personal residence by Carlos Zamora. Image courtesy Black Cat Books.

In her essay "Architecture in Mexico" McCoy heavily cited from Yanez's

18 Residencias de Arquitectos Mexicanos - 18 Homes of Mexican Architects (see above) published in March 1951 and which also included many of the same architects featured in this issue of

Arts & Architecture and Myers' book. The above Carlos Zamora cover photo of Enrique Del Moral's personal residence completed in 1949 in Tacubaya, for example, also appeared in both Myers' book and McCoy's article August 1951

A&A article. Fascinatingly, most of the photos of the interiors of these 18 architect's personal residences included furniture by Clara Porset, Mexico's answer to Charles and Ray Eames. This seemingly indicates that the architects were providing McCoy, via Timberman, their favorite images from their Mexican photographers which were also in Myers' possession. They also provided access to Timberman to take supplemental photos.

Diego Rivera with Frida's dog, ca. 1950. Photo by Elizabeth Timberman.

Not only were Timberman and Zamora competitors for architectural clients, they both were in Diego Rivera's orbit evidenced by the above and below images. I personally favor the whimsical Zamora image as I do his striking architectural work.

Diego Rivera with Frida's dog, ca. 1950. Photo by Guillermo Zamoya. From Archives of American Art.

Arts & Architecture, August 1951. Luis Barragan's personal residence, Tacubaya, 1950. Photo by Armando Salas Portugal.

McCoy selected Armando Salas Portugal's photo of Luis Barragan's patio from Yanez's book for the above August 1951

A&A cover but unfortunately did not credit him for the above image. Interestingly, Myers used Timberman's prints to illustrate Barragan's house in his book clearly indicating that the enterprising Timberman was also in direct contact with him as she was with the other architects McCoy featured. It is not clear whether Timberman and Myers interacted before or after her 1951 collaboration with McCoy but it was most likely before. Timberman may also have traded her new photos requested by McCoy for the architect's Mexican photographer's photos and forwarded them to McCoy along with her own.

(Author's note: I have not found any correspondence between McCoy and Timberman to corroborate any of the above speculation).

A partial explanation of the confusion over the duplication of the photo sources for Myers' book and McCoy's articles was found in the below exchange between McCoy and Porset discussing her apparent lack of access to architectural photographer Guillermo Zamora's striking photos. McCoy somewhat disingenuously complained,

"I understand from O.G. [Juan O'Gorman] that Porky [Myers] has got the gate, poor Porky, but he has been able to get [Guillermo] Zamora to tie up all his pictures and give me none, which is an enormous inconvenience to me. How can I convince the architects that magazine publication does not interfere with book publication? All of Neutra's work is published in magazines before book publication. Apparently he is so new in the field of publication of architectural that he is unaware of the procedure. If not that, he resents anyone else working in the same field, which is unbelievable, since in the States there are so many of us working amicably together. I feel that if this state continues it may have a vicious effect on the publication of material in the States. I want to get material for Arts & Architecture, but if I have to clear everything I want through Myers I see many delays and much trouble. Can you suggest some one person I could talk with who could help me in this matter?" (Esther McCoy to Clara Porset, December 17, 1951, Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 29).

I speculate that Myers had by then seen the July and August issues of

Arts & Architecture and had prevailed upon Zamora for exclusivity for the nearly 100 of his images he was planning to use in the book. Despite already publishing many of Zamora's photos in the August 1951 issue of

A&A McCoy was seemingly upset about being denied use his photos for future articles. At the time Zamora's work was on a par with Julius Shulman's (see Myers' and Yanez's book covers above for example) thus McCoy's concern was quite understandable. McCoy's problems with Myers presaged her future issues with Jean Murray Bangs Harris over access to the Greene & Greene and Bernard Maybeck archives as discussed in detail later below.

(Author's note: McCoy had been in simultaneous contact with her longtime collaborator Julius Shulman throughout 1951 bringing him in on the deal to market Porset's furnitore and discussing the opportunities Mexico provided for future articles. She apparently finally convinced him to join her there in early 1952. (McCoy to Shulman, December 26, 1951. Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 29)).

McCoy's and Shulman's

fledgling furniture business partner sympathetically responded,

"I don't see any reason why Myers should control, as in a monopoly, photographs of Mexican architecture. Nor do I think that he has been authorized to do it by any one. I do think that you should see Yanez about it and I will take you to him after the holidays. Myers gives a great deal of trouble in many ways. The attempt to monopolize Mexico is only one more." (Clara Porset to Esther McCoy, December 19, 1951, Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 29). (Author's note: McCoy had been in simultaneous contact with her longtime collaborator Julius Shulman throughout 1951 discussing the opportunities Mexico provided for future articles and finally convinced him to join her there in early 1952. (McCoy to Shulman, December 26, 1951. Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 29)).

Yanez and Porset were at the time busily collaborating on the rapidly approaching exhibition "The Art of Everyday Living" exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts slated to open on April 17, 1952 (see catalog below). This was the same venue as the modern architecture exhibition had taken place in early 1951. This exhibition of objects of good design made in Mexico was mainly curated by Porset and was based on New York's Museum of Modern Art's annual

"Good Design" shows which began as early as 1944. Porset was quite familiar with MOMA's exhibitions as she and husband Xavier Guerrero had submitted entries in the Latin American Competition for MOMA's "Organic Design in Home

Furnishings" exhibition (see below).

Xavier Guerrero and Clara Porset, Entry Panel for MoMA Latin American Competition for Organic Design in Home Furnishings, 1940. From MOMA Design Collections.

"The designs for this entry to the Museum’s competition were

described as peasant furniture to be made of pine with webbing of ixtle - a

locally available plant fiber in Mexico - on the cot and chair. The wall case has

jute screening in the sliding doors and at the end. These competition designs

were developed to furnish the Coyoacán housing project for Mexican farm

families in 1947. Porset was not recognized at the time this entry was

submitted but has since been credited for the design alongside Guerrero." From MOMA Design Collections."

Porset's furniture was liberally featured in the catalog alongside, as at MOMA, ceramics, pottery, glassware, dinnerware, cookware, Kitchen appliances, lighting, textiles, and native arts and crafts. The exhibition design was state of the art (see two below for example).

El Arte en la Vida Diara : exposicion de objectos de buen diseno hechos en Mexico edited by Enrique Yanez and Clara Porset, Palacio del Bella Artes, Mexico City, April 1952. Courtesy Getty Research Institute.

El Arte en la Vida Diara : exposicion de objectos de buen diseno hechos en Mexico installation, Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, April 1952. Photo mural by Lola Alvarez Bravo. From Clara Porset: Una Vida Inquieta, Una Obra Sin Igual by Oscar Salinas Flores, p. 46.

Taking another note from Myers' by then published book, Entenza and McCoy followed up yet again with an August 1952 article on the "Ciudad Universitaria de Mexico. In October 1952 the

Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, as part of an issue devoted totally to modern Mexican architecture, furniture, arts and crafts, published numerous McCoy articles including "Barragan's House," "You'll Sit Low in Mexico" on Porset's chairs, "A House for $1500" on Jaime Lopez Bermudez's personal residence, "Tract House" on Max Cetto's personal residence, and "Art in Industry" by her hopeful business partner Clara Porset which was illustrated with images from the above exhibition catalog. This

Home Magazine issue built nicely upon the July 1951

Arts & Architecture Mexico issue and was almost exclusively illustrated with the same Timberman and Zamora prints that Myers also used.

(McCoy, Esther, "Barragan's House," et al, Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, October 19, 1952, pp. 8-9, 16. Porset, Clara, "Art in Industry," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, October 19, 1952, p. 15. Author's note: McCoy's Papers at the Archives of American Art contain dozens of Zamora's wonderful photographs in her Mexicaan architect files. Author's note: On a roll with Porset's help, McCoy published articles on El Pedregal in the Mexican publications Espacios and Arquitectura the same year.).

A Guide to the Architecture of Southern California, 1769-1956 edited by Douglas Honnold, Reinhold Publishing Co., 1956. (From my collection).

Along with Julius Shulman, USC Dean of Architecture Arthur Gallion, McCoy's Arts & Architecture editor John Entenza, Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Millier and head of Art Center School Edward Adams, Myers was also heavily involved in assisting editor Douglas Honnold in the compilation of the influential A Guide to the Architecture of Southern California, 1769-1956. The guide was published in conjunction with the 1956 A.I.A. national convention held in Los Angeles. Oddly, Esther McCoy seems not to have been involved in the preparation of this seminal guide book. There might have been lingering feelings of animosity between McCoy and Myers which precluded both from participating or more likely, she may have been busy with the upcoming "The Roots of California Contemporary Architecture" exhibition (discussed earlier above). In any event, Honnold was wise to tap Myers' expertise as he was at the time also working on a comprehensive book on California architectural history which, to McCoy's apparent benefit, was not completed due to his untimely 1963 death. ("Publicist for Architectural Firm Selected," Los Angeles Times, June 15, 1958, p. VI-4).

Also in conjunction with the A.I.A. national convention, the busy Myers initiated the bringing to Los Angeles a photographic survey of contemporary Mexican architecture under the auspices of the Mexico's Ministry of Fine Arts, the same organization which funded his earlier book research. The 4500 square foot exhibition opened at the Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Park on May 14th and ran until mid-June to be ironically followed in the same venue in October by McCoy's "The Roots of California Contemporary Architecture" show. (Mexico, Finland Unveil Architectural Exhibits," Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1956, p. 17).

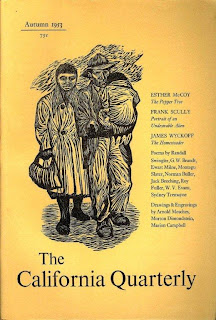

McCoy, Esther, "The Pepper Tree," California Quarterly, Autumn 1953, pp. 3-30. Cover illustration and illustrations in McCoy's "The Pepper Tree" by Morton Dimondstein. From my collection.

The California Quarterly, a relatively short-lived early 1950s literary review, hoped "to encourage writing that faces up to its time - writers who recognize their responsibility to deal with reality in communicable terms." McCoy's moving novella in the Autumn 1953 issue (see above) took a poignant look at a second generation Japanese American family in California during World War II who lost their family business, heritage and dignity and were forced to relocate to an internment camp. The contributor's notes highlighted her rapidly growing resume thusly,

"Esther McCoy has published fiction in The New Yorker, Harper's Bazaar, and a number of university publications. One of her stories was included in [Martha Foley's] Best [American] Short Stories of 1950. She is on the editorial advisory board of Arts & Architecture, and recently wrote two issues for them on Mexican architecture. She is at present working on a series of studies on California indigenous architecture and the work of the early moderns; some of these have been published this year in Arts & Architecture." (p. 2).

McCoy, Esther, "The California House," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, July 19, 1953, pp. 12-18, 37.

Presaging her 1956 "Roots of California Contemporary Architecture" exhibition and 1960 book

Five California Architects (see later below) in a July 1953

Los Angeles Times Home Magazine issue featuring the evolution of the California House (see above), McCoy illustrated Greene & Greene's Culbertson House, Frank Lloyd Wright's Freeman House, R. M. Schindler's Kings Road House and Richard Neutra's Lovell Health House, all with photos by Julius Shulman. This was the first article in which she contemplated a chronology of the beginnings of California modernist architecture.

McCoy, Esther, "The California House: 1897," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, July 19, 1953, pp. 14, 37.

Likely extremely proud of her 8-page

Home Magazine spread, she also sent it off to Schindler a few short weeks before his passing. She was undoubtedly quite taken aback by the below critique from her dying mentor which undoubtedly shaped her future thinking regarding the brothers.

"My reaction to your [above] article has been simmering in me for two days - and in order to regain my piece of mind I have to get it out of my system. I believe you went way off the beam about Greene & Greene - you should make a difference between the architects who's work reaches the dream of ideas and the ones who just have a good past for it. To credit one of the later like Greene with creative pioneering is absurd. His basic conception of the house was quite general at the time & you can look it up in one or two books (English & German) published at the time which describe what an English gentleman expects from his country house. Greene's development of this theme was commendable - but woody, sprinkled with a little Japanese influence, but in fact had nothing to do with California. In fact some public reaction was so strong that it discarded it completely for a period of Spanish architecture which although still foreign was much closer to the landscape.

You credit Greene with innovations without clarifying the terms - The "Storage wall" could only be conceived on the basis of space architecture - Greene may have assembled in a row of closets but they always were inside a completely walled in room, built against a solid back wall. This is a world from what "Storage Wall" means. You credit him with the patio - again you mistake the garden terrace, court, etc. of the English house with the modern patio idea creating an out door room as part of the house for outdoor living. Greene put very solid doors between and expected you to take a hat & muffler before taking a walk in the garden.

Incidentally since they are not Siamese twins a critical study would have to trace responsibility to the one brain - ideas do not come out of space between. You say he turned the house to the garden? - He never thought of a street front - he was building on large estates - the house had an English fore court - and obviously the living rooms did not face that. The "Revolutionary" idea of abandoning the street front could only happen on a standard city lot after intense traffic got too close. California architecture does not start with Greene (who never started anything) but only after rejecting him. His solidly walled houses with half-timbered walls, his heavy overhangs of thick solid Northern timber construction and his square leaded and barred windows.

P.S. My house was built outside L.A. and never needed a permit. Hope nobody catches on. Gill, who you don't even mention, was the first one to bend the Spanish into Californian and Neutra, whom you include, fought tooth and nail for "International." (Esther McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art, Box 27, Folder 37, 28-30).

McCoy may also have recalled her earlier response to her idol when he asked her why she hadn't submitted her "Space Architecture" in Direction to him for his approval. "Don't you want it to be right?" he asked incredulously. She proudly replied, "No. I want it to be mine." In this case, and many others over the years, she definitely could have used a friendly critique before publication. When asked by aspiring writers approaching her for advice over time she would similarly respond, "Make it your own." (Morgan, Susan, "Essay: Writing Home," in Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader edited by Susan Morgan, East of Borneo Books, 2012, p. 10).

This attitude is proving to have been her scholarship Achilles heal. Being less than an exhaustive researcher and fact-checker and loathe to provide footnotes and back matter in her publications, likely in a conscious attempt to "make them her own," on-going research is gradually chipping away at her reputation as a researcher but not her forever sterling reputation as a true writer's writer.

Roots of Contemporary American Architecture by Lewis Mumford, Reinhold, 1952.

McCoy's inspiration for her 1956 "Roots of California Contemporary Architecture" exhibition

undoubtedly came from Lewis Mumford's

Roots of Contemporary American Architecture (see above) which referenced the work of Greene & Greene, Bernard Maybeck, Irving Gill, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Richard Neutra. This is evidenced by a letter from Mumford indicating that the enterprising McCoy had eagerly shared her

L.A. Times article with him and that she had begun an in-depth study of Gill likely inspired by Schindler's admonishment for leaving him out of her

L.A. Times piece. She also solicited support for a second attempt at a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Mumford responded positively and particularly encouraged her Gill research. McCoy had recently met San Diego native, architect, lifelong Gill scholar and future Kings Road tenant

John Reed and emboldened by his knowledge and support was eagerly digging in to Gill's life's work with the assistance of her new friend and tour guide. McCoy had also informed Mumford of Schindler's recent death to which he replied, "I am sorry to hear about Schindler's death. He kept the ball in the air at a time when few were capable of even kicking it along the ground."

(Lewis Mumford to Esther McCoy, October 30, 1953. Esther McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art, Box 3, Folder 16. Author's note: Reed himself had first learned of Gill after having discovered Mumford's Sticks and Stones and The Brown Decades as an architectural student in the late 1940s. It is not yet known whether McCoy knew Mumford from her time in New York.)

A Guide to Contemporary Architecture in Southern California edited by Frank Harris and Weston Bonenberger, Watling & Company, Los Angeles, 1951. Cover design by Alvin Lustig and all images by Julius Shulman. (From author's collection).

An even earlier certain source of inspiration for McCoy's 1956 "Roots of California Contemporary Architecture" exhibition and 1960 book

Five California Architects (discussed in detail later below) was the above 1951

A Guide to Contemporary Architecture in Southern California. The guide was compiled by USC School of Architecture graduate students Frank Harris and Weston Bonenberger under the direction of Dean Arthur B. Gallion. This seminal publication was the first guide to focus solely on modern architecture, much of which was being produced by USC School of Architecture graduates. The introduction paid homage to the "roots" of California modernism with discussion of Irving Gill, Greene & Greene, Bernard Maybeck, Frank Lloyd Wright, R. M. Schindler, Harwell Hamilton Harris, Gregory Ain, Raphael Soriano and the Case Study House Program. Published while McCoy was still focused on modern architecture in Mexico, the guide provided an invaluable preview to most of the architects she later featured in her work.

(Author's note: The first attempt at creating a modern architecture guide for Southern California I have been able to locate is a map-guide titled "The New Tradition" prepared by Annita Delano and Joseph Hull for display at the November 1940 "Exhibition on the

growth and development of distinctive architecture in Southern California" at UCLA curated by Art Professor Annita Delano. "Among Other Things," California Arts & Architecture, November 1940, p. 12). (For much on Delano see my Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism).

Greene & Greene and Irving Gill examples singled out in the Guide introduction (see excerpt below).

In the guide's introduction Bonenberger and Harris compared the work of Gill and Greene & Greene while referencing their recent rediscovery (by Jean Murray Bangs Harris) (see more detailed discussion later below).

"There seems to be no evidence of any eclectic reversion on the part of the three men who were practicing in the southern part of the state at the same time. Two of these people were brothers, Charles and Henry Greene, and the other was Irving Gill. Although the design done by the Greenes had a widespread and easily recognized effect on building in the area, the men themselves went unheralded until very recently, many years after they had discontinued practice. Mr. Gill's work was not widely accepted or publicized, but before his death in 1936 he received some recognition in magazines and quite some acclaim in Europe. The copies of Greene & Greene work are numerous and readily identified, but if Gill had any imitators they are well hidden in the profusion of buildings with the piaster exterior that he liked to use. In point of design the work of Gill is almost the antithesis of that executed by the Brothers Greene. While Gill expresses a definite anticipation of the yet undeveloped International Style in his use of very simple forms and complete lack of ornament, the Greenes exhibited an oriental decorative quality created by their use of wood structure and intricate detailing. Also, there is evidence that Gill's chief interest was in low-cost housing for workers, but it seems quite apparent that the architecture produced by the Greenes was only for the wealthy. Gill worked for some years in Louis Sullivan's office along with Frank Lloyd Wright, and examples of his work also appear on the east coast." (Ibid, pp. 4-5).

All photographs in the guide were provided by soon-to-be longtime McCoy collaborator Julius Shulman. The

Alvin Lustig cover design also presaged McCoy's 1984 highly ambitious

Guide to U.S. Architecture: 1940-1980 created by graphic designer Joe Molloy (see much later below).

Announcement for Schindler Memorial Exhibition, May 17 - June 5, 1954 at the Landau Gallery. Courtesy Archives of American Art, McCoy Papers, Box 27, Folder 29.

Possibly inspired by the hoopla over the upcoming June 1954 Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition at Barnsdall Park, McCoy's recently befriended historian sidekick, guide and late 1940s USC architecture student

John Reed suggested to that they "do something" for Schindler at his brother Orell "O. P." Reed's

Felix Landau Gallery on La Cienega Blvd.

(John Reed interview by author, November 4, 2014). Reed had in the fall of 1951, arranged similar Landau Gallery exhibitions for Richard Neutra, John Lautner, Victor Gruen and Welton Becket which Esther most likely attended between her early and late 1951 trips to Mexico (see discussion later below). Reed and McCoy proceeded to curate the May-June 1954 Schindler Memorial Exhibition at O. P.'s gallery (see announcement above).

(For example: "Neutra to Lecture," Los Angeles Times, November 9, 1951, p. V-8). Reed recollected Pauline Schindler giving him and McCoy access to Schindler's papers to prepare for the show. A period article in the

L.A. Times by Schindler-Weston circle friend Arthur Millier stated that Reed had prepared the display.

(Millier, Arthur, "Tribute Paid Pioneer Architect," Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1954, p. V-7).

Schindler-Neutra apprentice Gregory Ain, one of Reed's instructors at USC, gave a gallery talk on opening night followed by a slide show of Schindler's projects by Reed. Reed coincidentally managed his architectural office out of Schindler's Kings Road House between 1960 and 1965 (see more on this later below). (John Reed interview with the author, July 1, 2014.).

Above is a photo of McCoy and other former Schindler draftsmen including Case Study House architect Rodney Walker at the May 17th formal exhibition opening viewing a copy of the catalog. This august group spoke at a repeat opening two weeks later which had to be scheduled due to popular demand. The opening event was so crowded with Schindler fans that many people could not get into the relatively small gallery space causing a clamoring commotion and traffic problems on the street and sidewalks outside. (ibid).

McCoy, Esther, "R. M. Schindler, 1890-1953", Arts & Architecture, May 1954, pp. 12-15, 35-36. From Arts & Architecture, 1945-54: The Complete Reprint. (From my collection).

The above May issue of

Arts & Architecture included a companion Schindler retrospective "correlated" by McCoy with a lengthy introduction by Gregory Ain and also announced the memorial exhibition at the Landau Gallery. The four-page photo spread featured 30 Shulman photos of Schindler's work and tributes from colleagues submitted in response to requests from Schindler's son Mark.

(Original tribute letters in the Schindler Papers at UC-Santa Barbara.).

Having referenced Frank Lloyd Wright's Sixty Years of Living Architecture exhibition at Barnsdall Park (see above) in early March in a story featuring his Storer, Sturges and Obeler Houses, McCoy and Reed took great pains to ensure that Schindler's exhibition opened before Wright's blockbuster global traveling show which received much hype in the local press leading up to its June 1st opening. (McCoy, Esther, "Frank Lloyd Wright: 60 Years of Living Architecture," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, March 7, 1954, pp. 10-11, 41

Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Los Angeles Municipal Art Commission, Barnsdall Park, 1954, exhibition catalogue, back cover.

Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Los Angeles Municipal Art Commission, Barsdall Park, 1954, exhibition catalogue, front cover. (From author's collection).

McCoy and Reed undoubtedly hoped that Wright would view their memorial tribute to Schindler since the new exhibition pavilion he designed for his show was on the same site that brought him and Schindler to Los Angeles in the first place, i.e., Aline Barnsdall's Olive Hill. I have not yet been able to determine if Wright viewed his erstwhile apprentice's retrospective or met McCoy, but it seems likely that his later apprentice Richard Neutra would have informed him about it as he and Dione also attended the Wright opening (see below) as did John Reed, McCoy, and Pauline Schindler. Wright sent his grandson Eric from Taliesin to help install the exhibition in the hastily constructed pavilion he had specially designed to house the show. ("Architect Wright to be at Preview," Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1954, p. I-6 and Author conversation with John Reed and Mary and Eric Lloyd Wright at their Malibu compound, July 20, 2014). (Author's note: Coincidentally, John Reed apprenticed with Lloyd Wright during 1949-51 during Eric's apprenticeship at Taliesin. Orrell and John Reed visited the Wrights at Taliesin West in 1949 where Reed shared with Wright his slides of Irving Gill's projects. Upon Wright's death Orrell handled Wright's considerable Japanese art collection to help Ogilvanna pay Wright's hefty estate taxes in order to save Taliesin from the auction block.).

Richard and Dione Neutra at Frank Lloyd Wright's Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Los Angeles Municipal Art Commission, Barsdall Park, 1954. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

On the heels of her and Reed's May-June Schindler exhibition and the June-July Wright exhibition, McCoy reviewed the AIA Southern California Chapter's 60th Anniversary Exhibition in August. Each of 500 local architects submitted their favorite projects for inclusion in this massive show which also included a survey of the work of L.A.'s early architects and historical buildings. McCoy began her Irving Gill myth making with this article by stating that he "...developed the first concrete house in the United States..." (McCoy, Esther, "Prize-Winning Work, AIA: Sixty Years of Architectural Progress," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, August 29, 1954, pp. 12-15).

Illustrated by numerous Julius Shulman photos of local national award-winning work, McCoy summed up the success of Southland architects in the national AIA Awards program also featured as part of the show thusly, "...and the fact that out of 66 awards given nationally 32 have been in California, and 19 of the 32 in Southern California, indicates the high quality of the work." (Ibid).

Roots of California Contemporary Architecture, 1956 exhibition catalog, text by Esther McCoy, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Park. (From my collection).

McCoy's next significant publication, the 1956 The Roots of California Contemporary Architecture (discussed earlier above) was published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name which opened at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Park. The catalog tied together and resurrected the work of our state's earliest modernists, Irving Gill, Bernard Maybeck,

Greene & Greene,

Frank Lloyd Wright, R. M. Schindler, and Richard Neutra. Listed contributors of material for the show were Henry Eggers, Jean Murray Bangs (wife of

Harwell Hamilton Harris whom McCoy featured in her 1984 book

The Second Generation), Professor

Kenneth Cardwell, Mark Schindler, Louis Gill, Sr. and Richard Neutra.

This highly popular exhibition traveled to the University of California Berkeley later in 1956 followed by a circuit through the Western Association of Museums.

(See "News and Views on Art," Los Angeles Times, October 21, 1956, p. IV-6 on the exhibits popularity and itinerary, Greene & Greene Collection: Writings and Lectures of Jean Murray Bangs, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University and Jean Murray Bangs Collection on Bernard Maybeck, 1904-1976, Bancroft Library, UC-Berkeley).

Jean Murray Bangs, 1937, the year she married Harwell Hamilton Harris. Photographer unknown. From Harwell Hamilton Harris by Lisa Germany, p. 53.

Bangs (see above), Harris and Eggers were instrumental in rescuing the drawings of the Greene and Greene and commissioning

Maynard Parker, Cole Weston and others to photograph their still-existing houses in the 1940s. Bangs was also instrumental in the rediscovery of Maybeck around the same time and obtained a grant to gather source materials and photograph his work. Back at her alma mater Berkeley (Economics, Class of 1919) during her husband's frequent visits to oversee construction of his iconic Havens House and two other Bay Area projects, Bangs first met Maybeck through the construction superintendent Walter Steilberg, supervisor of numerous Julia Morgan Bay Area projects.

(Germany, p. 94). Bangs had admired Maybeck's work since her college days attending classes in his Hearst Hall. Quickly befriending the by then cynical master she was able to convince him to entrust her with a large portion of his archive.

Harris and Bangs were also introduced to Greene and Greene's Thorsen House near the Havens House site by retired architect Walter Webber who was assisting Harwell on his San Francisco area projects. Webber warned Bangs, "They got Greene & Greene and they'll get your husband too." Webber meant that the Greenes were doomed to obscurity because of the ubiquitous replication of their designs. This remark stirred Bangs to learn as much as possible about the Greenes while concurrently pursuing her Maybeck interests (also see discussion later below).

(A New and Native Beauty: The Art and Craft of Greene & Greene by edited by Edward R. Bosleyand Anne E. Malik, Merrell, London, 2008, p. 241).

McCoy, Esther, "Yucatan", Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, April 29, 1956. Julius Shulman cover photo. (From my collection).

McCoy and Shulman collaborated on close to 100 articles for the Los Angeles Times Home Magazine including at least ten cover stories. The above April 29, 1956 issue of the highly popular weekly is an wonderful example of an entire number comprised of their collaborative work. The pair were commissioned to spend two glorious weeks traveling across Mexico where McCoy had spent mush time exploring Mexican modern architecture in the early 1950s (see discussion earlier above).

McCoy and Shulman pooled their considerable talents to bring to the Times readers an exciting eight-article travel adventure of architecture, crafts and history and they delivered in spades.

Gordon Drake, Berns Beach House, Malibu, 1951. Sunset, March 1954. Julius Shulman cover photo. Esther McCoy seated on deck. (From my collection).

McCoy recalled in her oral history, "Then Shulman asked me to do things for the Times, because so many of the architects... There were two places the house architects wanted to appear in, Home Magazine and Sunset." A great example of a McCoy-Shulman collaboration for Sunset was the above cover story on Gordon Drake's Berns Beach House in Malibu in the March 1954 issue. Architects also knew that being blessed by McCoy and Shulman greatly enhanced their chances for awards recognition. Furthermore the dynamic duo used this particular shoot to help market Sara Porset's chairs and textiles by another Mexico City via New York designer Saul Borisov (see below). (See for example my A Case Study in the Mechanics of Fame: Buff, Straub & Hensman, Julius Shulman, Esther McCoy and Case Study House No. 20 and The Post-War Publicity Partnership of Julius Shulman and Gordon Drake). (Many thanks to LACMA curator Staci Steinberger for identifying the Porset chairs and Borisov textile in the above and below photos.).

Borisov, Saul, "From Mexico's Looms," Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1952, p. I-20.

McCoy, Esther, "What I Believe...A Statement of Architectural Principles (by A. Quincy Jones and Frederick E. Emmons)", Los Angeles Times, February 19, 1956. From ProQuest.

McCoy's "What I Believe..." column was a regular fixture in the

Los Angeles Times Home Magazine from 1954 through 1956 in which she featured a different firm each month, mostly from Shulman's client list and including Shulman photos.

(See example above on A. Quincy Jones & Frederick E. Emmons).

McCoy's earlier-mentioned Candela exhibition,"Felix Candela: Shell Forms" (see catalog covers above and below) was held at Harris Hall on the USC campus. Photographs and drawings of 22 buildings and projects of shell forms in thin concrete were on display from May 12 through June 12 and was under the joint sponsorship of University of Southern California's Department of Fine Arts and School of Architecture, the Architectural Panel and the Southern California Chapter of the AIA.

(Author's note: The entire catalog and other Candela articles by McCoy can be viewed at the above AAA link. Note in particular the luminaries on the host committee and sponsors of the exhibition on the back cover below. For more on the context of this exhibition within the USC School of Architecture activities see my The Architecture of Bernard Judge: Living Lightly on the Land).

In an announcement for the show McCoy wrote,

"Engineers have for centuries envied nature's ability to construct shells of great delicacy and strength whose double curvature produces a surface which at no point is more vulnerable than another. But it was not until the development of reinforced concrete that this became possible for man. The first shell in architecture was the Zeiss factory in Germany and since that time this form has caught the imagination of designers in all countries.

The perfection of methods whereby nature's principles could be applied to architecture reached a milestone in 1950 with the design of Candela's Cosmic Ray Pavilion in Mexico's University City. A roof thin enough to admit cosmic rays was required and Candela designed and built a shell 5/8-inch thick, the thinnest ever to be poured.

In 1954 Candela was able, for the first time, to combine his talents as engineer and architect in the Church of Our Miraculous Lady. As in nature, the surfaces do not depend upon their thickness for their strength but upon the tension integrity of the material. In this new engineers' architecture is seen the mysterious connection between the laws of physics and our aesthetic sensibility." (McCoy, Esther, Interpretation of Nature," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, May 12, 1957, p. 34).

McCoy, Esther, "Felix Candela: Shells in Architecture," Evergreen Review, Winter 1959, pp. 127-33.

McCoy was in great literary and artistic company with her followup article on Candela in the prestigious literary journal

Evergreen Review. Also featured in the same issue were none other than poet

Octavio Paz, author

Elena Poniatkowska, novelist

Carlos Fuentes, muralist

Jose Luis Cuevas and numerous others.

The following year McCoy helped organize an exhibition for another noted Mexican architect,

Juan O'Gorman, which was on display at the Long Beach Museum of Art in November and December and then traveled to the

American Crayon Company Gallery designed by Richard Neutra the following January.

McCoy was also involved with an O'Gorman exhibition at Valley State College (now Cal-State Northridge) in 1964.

(McCoy, Esther, "O'Gorman Exhibit," Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, November 30, 1958, p. 24 and "Architect Will Speak at College, Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1964, p. VII-9. Author's note: John Reed recalls McCoy inviting him to accompany her to visit and stay with O'Gorman around this time per a November 4, 2104 interview.).

Irving Gill, 1870-1936 , exhibition catalogue, 1958, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (From my collection).

, exhibition catalogue, 1958, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (From my collection).

McCoy, noted architectural photographer

Marvin Rand, graphic designer

Louis Danziger, and soon-to-be Schindler Kings Road House tenant,

John Reed collaborated on the above

Irving Gill

catalog for the 1958 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (see above). McCoy wrote the 8,000 word essay which oddly contained only a single brief mention of Gill's residential masterpiece the Dodg House. LACMA assistant curator James H. Elliott arranged the exhibition and commissioned the catalog. In the catalogue foreword Elliott acknowledged Reed, "To John Reed who through his long interest in Gill's work was able to give invaluable assistance in locating and identifying buildings." Reed also recollected lecturing on Irving Gill in conjunction with the exhibition.

Architect-historian John Reed at Irving Gill's Horatio West Court Apts. for owner H. D. West, 140 Hollister St., Santa Monica looking much as it did when Reed and McCoy first visited around 60 years ago. Photo by John Crosse, July 15, 2014. The project is just a short walk down the hill to the beach from McCoy's personal residence.

In the mid-1950s Reed also designed a writer's studio addition for McCoy's personal residence adjacent to R. M. Schindler's earlier second-story addition (see below).

Esther McCoy Residence, 2434 Beverly Ave., Santa Monica. John Reed (left) and R. M. Schindler (right) second-story additions. Photo by John Crosse, July 15, 2014.

Five California Architects, Reinhold, 1960. Julius Shulman cover photo. (From my collection).

The Gill exhibition and McCoy's previous catalog for the 1956

The Roots of California Contemporary Architecture laid the groundwork for McCoy's (and Randall Makinson's) first full-scale book,

Five California Architects

(see above). This

was the first significant work published on R. M. Schindler and Irving Gill and which Randall Makinson also expanded upon Jean Murray Bangs' earlier published work on Greene & Greene and Bernard Maybeck listed in the following bibliography.

(Bangs, Jean Murray, On Greene & Greene: "A new appreciation of ''Greene and Greene',"Architectural Record,v.103(May 1948), p.138-140; "Greene and Greene,"Architectural Forum,v.89(Oct. 1948), p.80-89; "America has always been a great place for the prophet without honor,"House Beautiful,v.92 (May 1950), p.138-139, 178-179; Article was reprinted in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects, v.18 (July 1952), p. 11-16, under the title "Prophet without Honor; A parting salute to the fathers of the California style," House & Home, v. 12(Aug. 1957), p. 84-85. (For the most definitive and complete review yet on Bangs' rediscovery of Greene & Greene and Maybeck and her work with Elizabeth Gordon at House Beautiful, all of which McCoy is eerily silent on, see Ted Bosley's "Jean Murray Bangs and the Rebirth of Greene & Greene" in his chapter "Looking Both Ways: Modernizing the Past to Shape the Future" in Maynard L. Parker: Modern Photography and the American Dream edited by Jennifer A. Watts, Yale University Press, 2012, pp. 92-129). On Maybeck: "Bernard Ralph Maybeck, Architect, Comes Into His Own," Architectural Record, (January 1948, pp. 72-79: and "Maybeck - Medalist," Architectural Forum, (May, 1951), pp. 160-162). (For more on Bangs' work on Greene & Greene and Maybeck and as an architectural historian in general see "The Pace Setter Houses: Livable Modern in postwar America" by Monica Michelle Penick, University of Texas School of Architecture).

In addition to his Gill field research and slides, John Reed also shared his considerable Greene & Greene and Maybeck research with McCoy taking her on numerous Los Angeles, San Diego and Bay Area field trips. In her introductory acknowledgements McCoy again credited Reed, "to John August Reed, AIA, whose knowledge and appreciation of Gill first led me to attempt research on this subject."

(p. iv).

Likely with her dying mentor Schindler's earlier-quoted critique in mind, McCoy entrusted the chapter on Green & Greene to

Randell L. Makinson, then a recent graduate of USC's School of Architecture and in her acknowledgments credits him with studying the work of the Greenes on an AIA Rehmann Fellowship. Puzzlingly, nowhere in her acknowledgments or her and/or Makinson's text is Bangs' earlier published work on the Greenes and Maybeck or Bangs' collaboration on the previously-mentioned

Roots of California Contemporary Architecture exhibition credited. This and the fact that McCoy provided no bibliography and/or endnotes in either the first edition or the 1975 Praeger reprint resulted in the creation of the myth that she was the first to rediscover the Greenes and Maybeck. John Entenza's introduction to his longtime friend and

Arts & Architecture Editorial Advisory Board member's book is also silent on Bangs' (and Makinson's) contributions. Of McCoy he wrote,

"Of those who knew them [the five California architects] intimately or through painstaking studies unearthed their beginnings, Esther McCoy has brought to this book a careful and perceptive judgment, a loving recognition, and a sound critical eye."

A period review by

Marion Dean Ross, University of Oregon Professor of Art History and one of the 1940 founders of the Society of Architectural Historians, was not sympathetic. He took her to task for her narrow inclusional scope on the early pioneers and including Schindler (but not Neutra) who was a generation younger arrival on the scene. He continued,

"As it stands, the book is a collection of four separate

essays. Part of the material was originally prepared for periodical

publication, and the language retains a journalese flavor not entirely to its

advantage. There is no introductory material which might have set the

architectural scene in California at the beginning of this century, nor is

there any closing summary which might have placed the work of these architects

in relation to each other and to their times. The historically-minded reader

will find a number of questions unanswered.

More detailed stylistic analysis

and more thorough documentation would have made it a more useful book. There

are no footnotes, although some of the sources are referred to in the text.

There is an index, but there is neither a bibliography nor a list of

illustrations, both of which would have made the book more helpful to the

student.

Ross found McCoy's illustrations "in fact one of the major contributions of the book" and undocumented anecdotal account of the architect's lives "entertaining." He continued,

"From personal experience of the difficulty of locating

buildings by Maybeck in Berkeley, this reviewer would have liked to have had

the actual address of the surviving structures given somewhere in the book.

Even with the street number it is not always easy to find a building one wants

to see in the widespreading cities of California. ...

Ross concluded with some probing questions McCoy should, and easily could, have answered what with her closeness to Schindler,

Although the author avoids making any statement about the

comparative merit or relative importance of these architects, the reader almost

inevitably wants to do so. Are they all of equal importance? What exactly did

they have in common? What has been their influence on architecture in

California or elsewhere? These are some of the questions one would like to have

answered.

Gill's work before the first World War seems extraordinarily prophetic of what was to come in the late twenties and thirties, yet apparently had no connection with it. If Gill had not used round arched openings so often, his work would be scarcely distinguishable from much European work done a decade or so later. His design for Horatio Court West in Santa Monica, 1919 (p. 96) is singularly suggestive of Dutch work influenced by de Stijl. Schindler would appear to have taken up almost at the point Gill had

reached about 1920. What was the relationship between them? Mrs. McCoy tells us

only that Schindler had visited Gill in the nineteen-twenties (p. 192). Had

Schindler seen Gill's work on his visit to California in 1915? There is

obviously much more to be known about architecture in California in the early

part of this century. Let us hope that this book will stimulate further studies

either by Mrs. McCoy or others in this rich field for research." (Ross, M. D., Book Review: Esther McCoy, Five California Architects (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1960).

Greene & Greene at the James Residence, Carmel Highlands, 1947. (Boyhood summer home of Dan James, one of Dreiser's pall-bearers in the photo near the beginning of this piece). Photo by Cole Weston commissioned by Jean Murray Bangs for the exhibition on the brothers work at the Biltmore Hotel in March 1948. From USC Digital Library. (Author's note: McCoy used this exact same Bangs-commissioned Cole Weston photo to illustrate her July 19, 1953 article "In architecture, who starts a style?" Los Angeles Times Home Magazine indicating her awareness of Bangs' earlier work. Bangs was likely introduced to Cole Weston, by then living in Carmel permanently assisting his ailing father, by her lifelong friend Pauline Schindler. For much more on Cole see my "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage." For much on Pauline's lifelong friendship with the Weston family see my "Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism" and my "WWS").

Harwell Hamilton Harris and Henry Mather Greene, 1950. Photo by Henry Dart Greene. From A New and Native Beauty: The Art and Craft of Greene & Greene edited by Ted Bosley and Anne Mallek, p. 248. Courtesy Virginia Dart Greene Hales.

Abe Plotkin and Jean Murray Bangs ca. 1922. Photographer unknown. From the scrapbook compiled by Bangs and Plotkin courtesy of Harris biographer Lisa Germany.

I can't help but wonder if Bangs and Harris's,

and Pauline Schindler's father, Edmund Gibling's falling out with McCoy's friend and benefactor John Entenza

over the underhanded way he gained ownership of California Arts & Architecture from their dear friend Jere Johnson in 1940 had anything to do with McCoy's silence on Bangs. It was likely through Bangs' friendship with

CA&A's editor Jere Johnson that Pauline's father was able to find his job as an ad salesman with the publication in 1939.

Pauline, social worker Bangs and her garment workers union labor organizer husband

Abe Plotkin (see above)

had become quite close since bonding over labor issues and social causes she they were mutually involved with in early 1920s Los Angles. Pauline was keenly interested in Plotkin's work for the ILGWU since she was arrested for picketing for the same union in Chicago in 1915. (See my WWS). By this time,

Entenza is likely to have shared his side of the story

with his confidant McCoy. (For much more on Entenza's hostile takeover of CA&A see my discussion below on McCoy's Modern California Houses: Case Study Houses 1945-1962 and California Arts & Architecture: A Steppingstone to Fame: Harwell Hamilton Harris and John Entenza: Two Case Studies. Author's note: Per Harris biographer Lisa Germany it was Bangs who took the iconic photo of R. M. Schindler and the Neutras upon the Neutra's arrival at Kings Road from Taliesin in March 1925 seen below and early in my PGS.).

The Neutra family on their day of arrival at Kings Road from Taliesin, March 1925. Photo by Jean Murray Bangs. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.).

Erven Jourdan letter to Charles Sumner Greene, typed letter signed, July 1, 1950. From USC Digital Library.

McCoy's silence is deafening in light of the traveling exhibition on the Greene's organized by Bangs which opened at the Biltmore Hotel in March 1948 and the trouble she and film maker Erven Jourdan had with Bangs over the exclusion of the work of Greene & Greene from their 1950 film collaboration titled "Architecture West" (see above for example). Pauline Schindler assisted McCoy's efforts on the film by accompanying her on a location scouting trip to Carmel, introducing her to Edward Weston and Charles Sumner Greene and giving her tours of Greene's Studio and iconic James Residence in Carmel Highlands, a short walk from Weston's Wildcat Hill studio, and Bernard Maybeck's Harrison Memorial Library. (Pauline Schindler and Esther McCoy signatures in Edward Weston's guest book, Wildcat Hill, November 4, 1949).

Bangs' Greene & Greene exhibition reached New York's Architectural League by the time her 1951 issue of the Los Angeles Times Home Magazine also dedicated to the Greenes (see below) admonished Angelenos to resurrect and take pride in the brothers' seminal work. McCoy, in her formative years as an architectural historian, most likely attended the exhibition and read Bangs' Home Magazine issue and her other numerous articles on the pair, thus her oversight can only be construed as intentional.

(Author's note: McCoy's first work on the Greenes was not published until the below 1953.).

Bangs, Jean Murray, "Los Angeles.. Know Thyself!" Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, October 14, 1951, cover, entire issue devoted to Greene & Greene. From Los Angeles Public Library-ProQuest.

The below article inset reads,

"Material on the work of Greene & Greene in this issue is from the forthcoming book by Jean Murray Bangs, a resident of Pasadena and Los Angeles since 1909. Miss Bangs is the wife of Harwell Hamilton Harris, director, the School of Architecture, University of Texas. An exhibition of Greene & Greene work opens coming week at the New York Architectural League."