(Click on images to enlarge)

Irving Gill, ca. 1915. Photographer unknown. Schaffer, Sarah J. "A Significant Sentence Upon the Earth: Irving J. Gill, Progressive Architect, Part I: New York to Chicago," Journal of San Diego History, Fall 1997, front cover, pp. 218-239. (From my collection).

Louis Sullivan, 1890. Photograph by Hesler. From the Chicago History Museum.

Dankmar Adler, January 12, 1891. From the Art Institute of Chicago.

Auditorium Building, 50 E. Congress St., Chicago, 1889. Adler and Sullivan, architects.

The evolution of modernism in Los Angeles architecture can arguably be traced back to the Auditorium Building offices of Adler & Sullivan in the early 1890s. The Auditorium Building (see above) was Adler & Sullivan's crowning achievement and met with rave reviews in the local and national press and trade journals as setting the bar for buildings of its typology upon its 1889-90 completion. The now-famous partners and their chief draftsman, Frank Lloyd Wright, excitedly moved their offices into their masterpiece of engineering and interior design's tower penthouse as the congratulatory accolades flowed over them (see below).

"New Offices of Adler & Sullivan, Architects, Chicago," Engineering and Building Record, June 7, 1890, p. 5.

Having had no formal education in architecture, Irving Gill first apprenticed to architect Ellis G. Hall in Syracuse around 1888-9. The fledgling architect then moved to Chicago in 1890. Upon his arrival, he first worked for Frank Lloyd Wright's employer, Joseph Lyman Silsbee. By 1891, Gill had unwittingly followed Wright's footsteps to the very prestigious firm of Adler and Sullivan. He was possibly attracted by the firm's work while watching the erection of the Auditorium Building, or perhaps was responding to a call for help to prepare plans for the Transportation Building for Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition (see below). (Schaffer, pp. 220-221).

Transportation Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Adler & Sullivan, architects.

Adler and Sullivan's Transportation Building and Sullivan's other Chicago work would also have made a lasting impression on R. M. Schindler's and Richard Neutra's mentor Adolf Loos during his fateful 1893-6 visit to the U.S.. Wright's 1911 European publication of his Wasmuth Portfolio (Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright), which his son Lloyd and his periodic draftsman Taylor Woolley helped prepare in Italy in 1909-10, also had an immediate impact on Loos and his impressionistic acolytes Schindler and Neutra. (For more on this, see my "R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra and Louis Sullivan's 'Kindergarten Chats" (Chats)).

The massive Transportation Building was clearly the most modernistic pavilion at the exposition and, as a result, received mixed reviews in the period press. In his autobiography, Sullivan wrote of the deleterious impact of the Exposition's surrounding architecture on his hard-fought battle for the acceptance of a more modern architectural language,

"Meanwhile the virus of the World's Fair, after a period of incubation ... began to show unmistakable signs of the nature of the contagion. There came a violent outbreak of the Classic and the Renaissance in the East, which slowly spread Westward, contaminating all that it touched, both at its source and outward.... By the time the market had been saturated, all sense of reality was gone. In its place, had come deep seated illusions, hallucinations, absence of pupillary reaction to light, absence of knee-reaction-symptoms all of progressive cerebral meningitis; the blanketing of the brain. Thus Architecture died in the land of the free and the home of the brave.... The damage wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer." (The Autobiography of an Idea by Louis Sullivan with a foreword by Claude Bragdon, Press of the American Institute of Architects, New York, 1924).

Irving Gill ca. 1890. From Hines, p. 35.

"He [Gill] might never have moved from Chicago to the West Coast if he had not had an unfortunate collision with Frank Lloyd Wright. Gill was so indiscreet, so Wright tells us, as to show up for work sporting the hair-do and the flowing black tie which the future lord of "Taliesin" had made very much his own. "This had been the case with others often enough, "Wright tells us, "'but in this instance the affair suddenly seemed to me more like caricature. I regarded him for a moment and said, 'Gill, for Christ's sake, get your hair cut.' The common enough exhortation, to which I have myself been subjected in nearly every province of the United States, was not pleasantly said. Gill was as rank an individualist as I and he quit then and there. But his individual character came out to good purpose in the good work he did later in San Diego and Los Angeles. His work was a kind of elimination which if coupled with a finer sense of proportion would have been -I think it was, anyway - a real contribution to our so-called modern movement." (Architecture, Ambition and Americans by Wayne Andrews, Harper Brothers, New York, 1955, p. 267 and Genius and the Mobocracy by Frank Lloyd Wright, New York, Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1949, p. 52).).

Frank Lloyd Wright ca. 1890. From Frank Lloyd Wright Library.

Like Wright, who was fired by Sullivan in July of 1893 for moonlighting, Gill also designed at least one house after hours while in Sullivan's employ; thus, one could seemingly speculate that he could have been fired for the same reason as Wright. ("[B. F. George Residence, 2833 Calumet Ave., Irving Gill, architect]" Real Estate and Building News (Chicago), January 14, 1893).

Gill's first San Diego office was in the very un-Sullivanesque Pierce-Morse Block at Sixth and F (see above). After partnering briefly with Joseph Falkenham in 1894-95, Gill joined forces with another former Chicago apprentice, William S. Hebbard (see below).

William S. Hebbard, n.d., photographer unknown. From the San Diego History Center.

Los Angeles County Courthouse, Temple St. and Broadway Ave., Curlett, Eisen and Cuthbertson, architects, 1889-91. From Water and Power Associates.

Los Angeles Orphanage at 917 South Boyle Ave., Curlett, Eisen, and Cuthbertson, architects, 1890. From Water and Power Associates.

By 1890, Hebbard established his own private practice in San

Diego. The following year, he became associated with the Reid Brothers, noted

designers of Hotel Del Coronado, and took over their San Diego

projects when that firm relocated to San Francisco, ca. 1892-3. In 1896, shortly

after Hebbard completed the very Sullivanesque U. S. Grant Building (see below)

in downtown San Diego, he and Gill joined forces to form a very successful

partnership. Before teaming with Gill, Hebbard designed work in an eclectic variety of styles, ranging from Sullivanesque to Richardsonian Romanesque, Mission Revival, Arts and Crafts, Tudor Revival, and others. The Hebbard & Gill firm arguably produced San Diego's

best architecture until its breakup in 1907.

U. S. Grant Building, 1036 5th St., San Diego, 1895. William S. Hebbard, architect. From the San Diego History Center.

In any event, Hebbard moved his office into the new building on September 1, 1895, where he would remain for the rest of his time in San Diego. It was here that he invited Gill to join him the following year. The younger Gill would have immediately taken note while the building was under construction and eagerly compared Sullivanesque notes with Hebbard on what was then likely one of the first "modern" buildings in San Diego. Gill also would have known of Hebbard's Sullivan-inspired Romona Town Hall completed about the time he arrived in San Diego in 1893 (see below). Hebbard and Gill maintained their offices in the Grant Building until dissolving their partnership in 1907. ("Among the Architects," Architect and Engineer of California, June 1907, p. 141. For much more on Hebbard and his partnership with Gill, see Flanagan, Kathleen, "William Sterling Hebbard: Consummate San Diego Architect," San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 1987.

Romona Town Hall, 1903, William S. Hebbard, architect. From the San Diego History Center.

It was during his 11-year partnership with Hebbard that Gill formed lasting relationships with San Diego's progressive philanthropic elite, such as Julius Wangenheim, George and Arthur Marston, and most importantly, Ellen Browning Scripps.

First Methodist Episcopal Church, 4th and D Streets, San Diego, Hebbard and Gill, architects, 1907.

After Gill parted ways with Hebbard in the spring of 1907, he and recently hired employee Frank Mead formed a brief but modernistically significant partnership with an office located in the First Methodist Episcopal Church building in downtown San Diego, which was just nearing completion. It was through Mead's recent Bureau of Indian Affairs connections that the partners landed the progressive clients Wheeler J. Bailey and Russell C. Allen.

Frank Mead, ca. 1914. Courtesy San Diego History Center.

(Author's note: Thanks to San Diego architectural historian Erik Hanson, I

was made aware of the above image of Mead.)

Mead's connections to the Baileys and Allen and later Alice Klauber resulted from his close association with mutual friends Natalie Curtis and Charles Lummis. Through Lummis's encouragement, Natalie Curtis became a noted Indian ethnomusicologist with close ties to Theodore Roosevelt. Through her largess, Roosevelt appointed Mead as his emissary to create the Yavapai Reservation in Arizona in 1903. For much more on Mead and his close friends Natalie Curtis and mutual friend Alice Klauber's mutual passionate interest and politically connected progressivism in Indian Affairs which attracted clients Wheeler Bailey and Russell Allen see my "Frank Mead: "A New Type of Architecture in the Southwest," Part I, 1890-1906").

Gill Cottages, 3732-34 1st St. (now Robinson Mews), San Diego, Irving Gill, architect. From Kamerling, Bruce, "Irving Gill: The Artist as Architect," San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Spring, 1979.

(Author's note: During his brief 1907 employment and partnership

with Gill, Mead was a tenant in one of Gill's above experimental cottages at

3732 1st St. (now Robinson Mews). (1907 San Diego City Directory).

Left: Wheeler J. Bailey Residence, La Jolla, 1907, Gill & Mead, architects. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive. Right: "A New Type of Architecture in the Southwest," by Natalie Curtis, The Craftsman, January 1914, pp. 330-336.

Gill and Mead were perhaps comparing their creative ideas and anxious to try them out without the probable domineering influence of senior partner Hebbard. The three residences created during their seven-month partnership began to exhibit the ornament-free, geometric elements for which Gill is now most fondly remembered. Finally breaking free from the elder Hebbard's yoke of Beaux-Arts eclecticism and romanticism and his own earlier Shingle Style influences gleaned from East Coast trips and projects during 1901-4 enabled Gill and Mead's remarkable Wheeler Bailey, Melville Klauber, and Russell Allen House designs in San Diego (see above and below). (Author's note: Mead's Moorish and Italian collonnade elements also inspired the design of the Homer Laughlin House in Los Angeles in 1908 after Mead's departure, as mentioned later herein.).

Bailey House interior. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

(Author's note: Bailey's keen interest in Indian artifacts and his later commissioning of Mead and Richard Requa to design a Pueblo style guest house in 1915 illustrate his appreciation of Mead's experience among the Southwest Indian community. See "Mead, Part II").

Bailey House interior, Kamerling, p. 51.

Melville Klauber Residence, Park Ave. and Redwood St., San Diego, 1908. Gill & Mead, architects. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive. (Author's note: Although all sources list the Klauber House as being completed in 1907, the building permit was apparently not issued until 1908. ("To Erect $21,000 Home at Beautiful Pasadena [sic]," LAH, March 15, p. III-5).

Artist studio in the Melville Klauber House. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

Russel C. Allen Residence, Bonita, 1907. Gill & Mead, architects. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive. (Author's note: Per George Curtis's Diaries at UCLA, Frank Mead was totally responsible for the design and construction of this house.).

This set the stage for Gill's first "modern" house in Los Angeles for client Homer Laughlin, Jr. The Design of the house was completed as his brief partnership with Mead was coming to an end in late November of 1907. Construction began in mid-May of 1908 and was completed by the end of the year. Homer Laughlin, Jr.'s role as Gill's first solo Los Angeles client and providing him with early patronage and introductions to other prospective clients among his prominent social circle is much under-recognized. ("Building Is Brisk, Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1908, p. II-1. Author's note: Hebbard and Gill had designed a heretofore unknown residence for O. J. Barker, President of Barker Brothers Furniture, at 1431 West Adams Blvd. in 1902.

The architectural patronage of Laughlin, Jr. and his father for John Parkinson, Harrison Albright, Irving Gill and others was at least as important as Aline Barnsdall's for Frank Lloyd Wright, R. M. Schindler and Lloyd Wright and Philip Lovell's for R. M. Schindler and Richard Neutra in the development of what we have come to define as modern architecture in Los Angeles. Gill's brief partnership with Mead and subsequent early mentorship of both Lloyd Wright and R. M. Schindler also played a crucial, seminal role in modernism's inevitable progression in Los Angeles.

Homer Laughlin, Jr.Residence, 666 W. 28th St., Irving Gill, architect, 1908. From "Concrete in Residence Design, Western Architect, August 1909, p. 17, and "Portfolio of Current Architecture: Residence of Homer Laughlin, Jr., Esq., Los Angeles, Cal., Irving J. Gill, Architect," Architectural Record, October 1912, p. 376.

The Laughlin House (see above and below) was a significant milestone in Gill's career. I hope to make the case with this essay that this particular collaboration of architect and client also laid a "concrete" foundation from which Los Angeles modern architecture arose. Gill's dramatic change in style, undoubtedly sparked by his brief partnership with Frank Mead, was a tack on to a definite new course beginning in 1907-08. (For much on Mead's Moorish and Pueblo influences on Gill's post-1907 work, see my "Frank Mead: 'A New Type of Architecture in the Southwest,' Part I, 1890-1906." See also Curtis, Natalie, "A New Type of Architecture in the Southwest," The Craftsman, January 1914, pp. 330-335. For an insightful analysis of Gill's earlier career, I recommend Irving J. Gill, Architect by Bruce Kamerling, San Diego Historical Society, 1993, and Irving Gill and the Architecture of Reform by Thomas S. Hines, Monacelli Press, New York, 2000.

Left: Laughlin Residence Garden Court. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive. Right: "The New Architecture of the West," The Craftsman, May 1916, pp. 140-151. (Author's note: Gill purposely omitted the Russell C. Allen House and the Wheeler Bailey House, designed by Frank Mead, from this article.)

Beginning in 1907, it was Gill's progressive elimination of architectural ornamentation and steady evolution towards an abstract reduction of the then-prevalent Mission Revival style to its most basic elements that cemented his modernist legacy.

Homer Laughlin, Jr. Residence, 666 W. 28th St., Los Angeles, 1908. Irving Gill, architect. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

From "Portfolio of Current Architecture: Residence of Homer Laughlin, Jr., Esq., Los Angeles, Cal., Irving J. Gill, Architect," Architectural Record, October 1912, p. 374.

The interior of the Laughlin House included more labor-saving devices than any of Gill's large houses up to that point. This was likely the reflection of a client with an engineering degree who would, within five years, begin his own engineering firm as discussed later below.

Homer Laughlin, Jr. Residence Garage Plans, 1908, Irving Gill, architect, Maury Diggs, draftsman. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

For the first time, Gill not only covered his kitchen and bathroom walls with concrete floors for sanitary reasons, but he also carried the feature throughout the house to eliminate dust-trapping surfaces. The house featured a central vacuum system with an outlet in each room, taking dust to the furnace. A garbage disposal in the kitchen drops garbage into an incinerator in the basement. The house was also equipped with an automatic gas heater and a Hygeia water filter. The ice box in the kitchen had access from the outside precluding the need for the ice delivery man to have to walk through the house. Milk was also delivered through a slot. Automobile enthusiast and later manufacturer (discussed later below), Laughlin, Jr.'s garage had an automatic car-washing machine and a service station-like maintenance pit (see above). Mail was delivered through a mailbox flush with the front door. ("Laughlin to Build New Residence; Will Be Model of Modern Construction, Los Angeles Herald (LAH), February 8, 1908, p. III-6).

From "Portfolio of Current Architecture: Residence of Homer Laughlin, Jr., Esq., Los Angeles, Cal., Irving J. Gill, Architect," Architectural Record, October 1912, p. 375.

Gill's incorporation of nature into his residential designs also began with the Laughlin House. Here he included an open-courted "garden room" (see above and below) drawing from the earlier adobe Mexican haciendas of which Gill opined "it is hard to devise a better, cozier, more convenient or practical scheme for a home." (Kamerling, p. 58).

Laughlin Garden Court. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

Harrison Albright, Sr., ca. 1909. Moody, Charles Amadon, "Makers of Los Angeles," Out West, April 1909, p. 316.

Searching for a connection for the source of Gill's Laughlin House commission and his fascination for concrete as a building material pointed me towards architect Harrison Albright as the most plausible candidate. Gill likely met the long-time reinforced concrete advocate Albright not too long after his March 1905 larger-than-life arrival in Los Angeles. On March 28th, Albright shared his portfolio with the California State Board of Architectural Examiners, whose well-respected Southern California branch president was none other than Gill's partner William S. Hebbard, license no A-9. Hebbard had been named to the first State Board upon its formation in 1901. Participation in Board activities required frequent travel to Los Angeles, the Board's Southern California headquarters. Hebbard's entree enabled Gill to obtain the lofty license no. A-62 shortly thereafter.

Albright likely shared with the Board his designs for the Waldo Hotel of Clarksburg, West Virginia; the Richmond Hotel in Richmond, Virginia (see later below), and the West Baden Springs Hotel of West Baden, West Virginia, among many others. Minutes of the Board meeting reveal that Albright "exhibited... many [photographs of his] large buildings [including] hotels, city halls, and police stations. . . .[and] in consideration of the magnitude of the work exhibited, it was moved that he be granted a certificate on account of his exhibits." Albright was granted license no. B-368 and set up shop in room 176 of the Chaffee Building. Hebbard likely shared the details of Albright's impressive presentation of reinforced concrete projects with his by then nine-year partner Gill. (Malinick, Cynthia B., "Harrison Albright's Architectural Contributions to Coronado," The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Spring 1997, Volume 43, Number 2).

In short order, Albright received his first local commission for a major addition to retired dinnerware industrialist Homer Laughlin, Sr.'s Laughlin Building at 317 S. Broadway. The original John Parkinson-designed building opened with much fanfare in the summer of 1898. ("The Laughlin Building: California's Finest Office Structure As It Is," Los Angeles Times (LAT), July 5, 1898, p. 26).

Homer Laughlin Building, 317 S. Broadway, John Parkinson, architect, 1898. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

The "fire-proof" claim for the steel-framed Laughlin Building was put to the test shortly after its July 1898 completion and passed with flying colors. An iron left on overnight in a fourth floor dress-making shop caused a fire but, "the fire-proof partitions and doors prevented the spread of flames to adjoining rooms. The cement floors and steel doors, and partitions were unharmed." ("Strictly Fire-Proof: The Laughlin Building Withstands a Severe Test," LAT, October 21, 1898, p. 9).

"Fifty-six-ton Test of Floor in Laughlin Building," LAT, September 10, 1905.

Albright's 1905 "fire-proof" addition was of reinforced concrete and was reportedly the first of its type in Los Angeles. Because of this, the construction was most likely being followed by both Hebbard and Gill, who had just begun experimenting with the material themselves. Gill possibly came up to Los Angeles to witness the strength tests ordered by the Building Department and reported on in the Times (see above). Albright's lecture on reinforced concrete to the Southern California Chapter of the American Institute of Architects shortly after the Laughlin addition's completion was also likely met with great interest by Gill, but with stiff resistance from much of the architectural and building contractor establishment. ("Hurl Bricks at Concrete: Sponsor for Hard Stuff Makes Weighty Defense," LAT, December 13, 1905, p. II-14). Albright would soon make Rooms 528-34 of the Laughlin Building his architectural offices for the rest of his time in Los Angeles. (Author's note: When Frank Lloyd Wright and son Lloyd selected a site for their Los Angeles office when work began on Aline Barnsdall's Hollyhock House in 1920, it was more than a coincidence that it happened to be in Room 522 of the Laughlin Building next door to his brother John's 1912-13 mentor's office. This will be explained in much more detail later below. (For much more on this, see my "R. M. Schindler, Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Lawrence Tibbett, Reginald Pole, Beatrice Wood and Their Dramatic Circles" (SWMZW)).

U. S. Grant, Jr., n.d., photographer unknown. From Amero, Richard W., "The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915," San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1.

Rendering of the U. S. Grant Hotel by E. C. Kent, Architect, Los Angeles and Hebbard and Gill, Associated Architects, San Diego. "By Builders and Architects: Good for San Diego," LAT, July 16, 1905, p. V-22, and "U. S. Grant Hotel, San Diego, Cal.," Out West, August 1905.

In 1903 U. S. Grant, Jr. (see two above) had commissioned E. C. Kent and Hebbard, and Gill to design preliminary plans for a grand new hotel befitting the burgeoning city of San Diego to replace the venerable Horton House Hotel, which his well-to-do wife had purchased in 1895 (see above). As mentioned earlier, Hebbard had in 1894 designed a summer home for U. S. Grant, Jr.'s brother Jesse, and in 1895 the Grant Building where Hebbard and Gill still maintained their office. At least as late as May 12, 1905 Hebbard and Gill were still on tap to prepare the plans for Grant's new hotel evidenced by a blurb in the Los Angeles Herald mentioning that Hebbard was in town staying at the Angelus Hotel and that he was "the architect of the $500,000 hotel shortly to be erected in San Diego with Los Angeles capital." ("Personal," LAH, May 12, 1907, p. 7).

Rendering for the U. S. Grant Hotel, San Diego, 1905. Harrison Albright, architect.

The hotel project was delayed until the summer of 1905, when the Horton House was finally demolished. (Ibid). Likely hearing of the excitement over Albright's "fireproof" reinforced concrete Laughlin Building Annex and making a construction site visit, Grant instead commissioned Albright to prepare final plans for a more elaborate reinforced concrete structure than first envisioned by Kent, Hebbard, and Gill two years earlier (see above and below). Grant had also most likely seen photos of and been impressed by Albright's recently completed Hotel Richmond on Richmond, Virginia's Capitol Square, a venue quite similar to San Diego's Horton Plaza (see two below). The irony of Grant's father's capture of Richmond in April of 1865, in effect, finally ending the Civil War, would not have been missed. It thus seems plausible that Gill and Albright could have had some form of interaction while the hotel design baton was being passed between the firms.

U. S. Grant Hotel letterhead extolling the hotel's fireproof properties. From a letter from John Olmsted to brother Frederick, January 4, 1911. From Panama-California Exposition Digital Archive. (Author's note: Grant would be elected President of the Panama-California Exposition in 1909 and re-elected in 1911.).

Hotel Richmond, 9th and Grace Streets on Capitol Square, Richmond, Virginia. Harrison Albright, architect, 1904. From CardCow.

Albright must have begun design on the hotel sometime during the summer of 1905 as the Los Angeles Herald reported in September that, "U. S. Grant, Jr., announces that he will be ready to call for bids for the construction of the new U. S. Grant hotel, which is to occupy the site of the demolished Horton house before the middle of next month. He desires to let the contract for the entire work to one responsible bidder." ("Expert Sent to San Diego," LAH, September 9, 1905, p. 5).

Carl Leonardt, ca 1913. Press Reference Library, Vol. II, International News Service, 1915, p. 486.

Excavation work commenced on the hotel on January 5, 1906, and was completed in July. The $311,115 reinforced concrete contract was awarded to Carl Leonardt of Los Angeles on July 20th. ("Gets Contract on Big Hotel," LAT, July 20, 1906, p. II-11). Leonardt had previously won the contract for the concrete work on Albright's Laughlin Annex, for which he employed renowned civil engineer and reinforced concrete expert Thomas Osborn to supervise construction. The death of Osborn while working on the U. S. Grant Hotel made headlines in the Los Angeles Times the following summer in a lengthy tribute highlighting his illustrious career. ("Prominent Man Passes Away: Re-Enforced [sic] Concrete Expert Dies at San Diego," LAT, July 20, 1907, p. I-7).

Albright's ongoing lectures on the safety and economic benefits of reinforced concrete were making a strong impact on the conservative businessmen in both San Diego and Los Angeles. A growing stream of San Diego commissions demanded that he spend more time there, just as Gill began spending more time in Los Angeles. The architects possibly forged a friendship or at least became professional acquaintances as Albright's projects made a big splash in both the San Diego and Los Angeles press. It also seems likely that Gill would have become acquainted with Albright's supervisor, Osborn, while following the hotel's construction progress.

Bixby Hotel, Long Beach, November 1906. John C. Austin and Frederick G. Brown, architects. From Austin, John C., "Says Collapse Started from Top," Architect and Engineer of California, November 1906, pp. 46-47.

Reinforced concrete was a very hot topic indeed in all of the architectural and building trade journals throughout the 1900s-1910s. Furthermore, the earthquake and fire in San Francisco in April 1906 and the collapse of the Bixby Hotel (see above) while it was under construction in Long Beach in November of the same year created intense local, regional and national scrutiny on the performance of reinforced concrete in the earthquake and the cause of the hotel collapse. The merits, construction techniques, and building codes regulating the use of the material were all hotly debated.

An investigative team, including legendary Los Angeles architect and fellow State Architectural Licensing Board member with Hebbard, Octavius Morgan, Harrison Albright, Charles Whittlesey, Carl Leonardt, and City of Los Angeles building inspector Thomas Fellows, investigated the Bixby Hotel collapse. ("Nine Men Killed in Collapse of Hotel," San Francisco Call, November 10, 1906, pp. 1, 5. For much more on the Gill-Fellows connections, do a "Fellows' search in my "Sarah B. Clark Residence, 7231 Hillside Ave., Hollywood, Spring 1913: Irving Gill's First Aiken System Project.

Morgan was quoted as he stood on a portion of the fifth floor that had not collapsed, "Good will come of it. ... Contractors have been in the habit of taking orders for concrete buildings too cheap and of taking too many chances in their construction. The lesson of this disaster should be a salutary one for architects and builders all over the country." ("Green Cement, Weak Supports," LAT, November 10, p. II-1).

Los Angeles Times, November 10, 1906, p. II-1.

Harrison Albright's reinforced concrete contractor, Carl Leonardt, was much more outspoken, placing blame on the "mongrel" use of unreinforced hollow block tile combined with reinforced concrete rather than using reinforced concrete throughout, and lack of proper shoring as the root cause of the disaster. He opined, "Could this building have been constructed under the regulations as laid down in the new reinforced concrete ordinance of our city, the disaster could not have occurred." (Ibid). Leonardt followed up with a lengthy illustrated article in the November 1906 issue of Architect and Engineer of California, which was also carried in Concrete two months later. (Leonardt, John, "The Failure of the Bixby Hotel," Architect and Engineer of California, November 1906, pp. 49-55 and "Why the Bixby Hotel Fell," Concrete, January 1907, pp. 30-31. Author's note: The a).

Temple Auditorium, 427 W. 5th St. Charles Whittlesey, architect, 1906. "A Triumph of Architecture," Pacific Outlook, October 20, 1906, cover, pp. 11-15.

Hayward Hotel, 6th and Spring Streets, 1906. Charles Whittlesey, architect. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Other much publicized Los Angeles reinforced concrete projects Gill would have been following with much interest were the Temple Auditorium and the very Sullivanesque Hayward Hotel (see above and below). Both were designed by noted California reinforced concrete expert architect and fellow Gill and Wright Louis Sullivan apprentice Charles Whittlesey of whose earlier Chicago work Gill would also have been very familiar with (see below for example). Coincidentally, the Temple Auditorium had its gala dedication celebration with a production of Verdi's "Aida," with Gill possibly in attendance the night before the Bixby Hotel disaster.

The Richardsonian Romanesque Fourth Baptist Church, Chicago, Charles F. Whittlesey, architect. Inland Architect and News Record, 1893.

Charles F. Whittlesey, architect from "As We See 'Em," A Volume of Cartoons and Caricatures of Los Angeles Citizens, E. A. Thompson, Los Angeles, [1906].

After surveying the Bixby ruins, Whittlesey also wrote an article for the November 1906 issue of Architect and Engineer of California, which was completely devoted to the analysis of the hotel collapse. He summarized his article with,

"This should be an object lesson to those having a little knowledge of the theory of reinforced concrete construction, yet lack the experience for its practical application. In this case I think that the blame cannot be with the architects of the building, for they frankly acknowledge their inexperience in reinforced concrete work and entrusted the structural design to engineers who professed a knowledge of the subject but who had had little or no practical experience."(Whittlesey, Charles, "Victory for Pure Type of Reinforced Concrete, Architect and Engineer of California, November 1906, pp. 48).

The Architect and Engineer of California, January 1907, front cover.

Two months later, the same magazine featured numerous articles on various aspects of reinforced concrete, including an article on Whittlesey's design for the Pacific Building in San Francisco, "World's Largest Reinforced Concrete Office Building," and by Albright on his Southern California reinforced construction projects then underway (see cover above). The projects illustrated were Albright's Santa Fe Railroad Freight Depot in Los Angeles, a Santa Fe passenger depot and hotel in Ash Fork, Arizona, a Santa Fe roundhouse in Bakersfield, and the U. S. Grant Hotel and the Union Building in downtown San Diego. (Albright, Harrison, "Reinforced Concrete Construction in Southern California," Architect and Engineer of California, January 1907, pp. 37-43). (Author's note: The cover of the February 1908 issue of the same magazine announced a feature story on the work of Whittlesey (see below).)

The Architect and Engineer of California, March 1908, front cover.

The ongoing national reportage of the Bixby Hotel disaster deeply intrigued Gill as it was around this time that he started regularly attending the monthly meetings of the Southern California Chapter of the AIA in Los Angeles. The sociable Gill also needed more professional contact than he was getting in San Diego. Attending Los Angeles meetings provided him with cross-pollination of L.A. design and building practices and professional organization camaraderie. The continuing discourse surrounding the investigation of the San Francisco earthquake and the Bixby Hotel collapse also most likely provided Gill with a thorough education in reinforced concrete building techniques (see below for example). Albright again lectured on the topic to the Los Angeles Architectural Club on March 12, 1907, with Gill likely in attendance. ("Los Angeles Architectural Club," Architect and Engineer of California, December 1906, p. 81).

Bassett, Wilbur, "Fatal Concrete Collapse," Technical World, February 1907, pp. 620-621.

Besides attending AIA meetings together in Los Angeles, by 1907 Gill and Albright were also exhibiting together. The Los Angeles Architectural Club planned its first annual exhibition in conjunction with the Arts and Crafts Society of Los Angeles for the third week of May 1907. Gill's rapid acceptance by his Los Angeles colleagues was evidenced by his being named one of the selection jurors, along with Elmer Grey, Augustus B. Higginson, Timothy Walsh, Charles Sumner Greene, Arthur Roland Kelly, Theodore Eisen, Frank Stiff, and Francis Pierpont Davis, for the Architectural Club. Four illustrations of Gill's work and Albright's rendering for the U.S. Grant Hotel were included in the show at the Associated Arts Hall at 718 S. Spring St. ("Arts and Crafts Will Show Drawings," LAH, April 6, 1907, p. 5, Anderson, Antony, "Art & Artists: A Joint Exhibition," LAT, Apr 14, 1907, p. VI-2 and "Los Angeles Architectural Exhibit," Architect and Engineer of California, June 1907, p. 84). ).

"Modern Way in Old San Diego," LAT, June 30, 1907, p. V-1.

The following month, an article featuring Albright's San Diego reinforced concrete work appeared in the Los Angeles Times. Construction photos of the Albright's U. S. Grant Hotel and the Spreckels Union Building, and the Scripps Building, designed by earlier Hebbard and Gill collaborator E. C. Kent, all in downtown San Diego, illustrated the piece. The article highlighted the scarcity of Portland Cement, exacerbated by the rebuilding of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake, as it had to be shipped all the way from Heidelberg, Germany, around the Cape of Good Hope via special freighters likely provided through the auspices of the Spreckels Brothers Commercial Company. (Ibid).

Gill must have been somewhat envious of the sheer size of Albright's San Diego commissions from 1906 through 1910, despite completing over 50 projects himself during this period. Besides the already mentioned $1,000,000 U. S. Grant Hotel and $1,000,000 Theater Building and San Diego Union Building for John Spreckels, a sampling of Albright's commissions also includes the Spreckels Mansion, Beach House and Free Public Library, all in Coronado, the Titus Residence, also in Coronado, and the $300,000 Timken Building in downtown San Diego. (Author's note: I recommend to the reader Bruce Kamerling's excellent Irving Gill, Architect and Thomas Hines's Irving Gill and the Architecture of Reform for a look at Gill's striking refinement of his clean edge, minimalist oeuvre during this seminal 1906-10 period leading up to his glory years in the early 1910s). Author's note: It was during this period that Frank Mead briefly formed a partnership with Gill and designed three projects, the Klauber, Bailey, and Allen Houses, as well as inspiring the design of the Laughlin House. See more on this at my "Frank Mead: A New Type of Architecture in the West, Part II, 1907-1920.

This article also perhaps prompted Homer Laughlin, Jr., and his wife, Ada, to choose Coronado for their summer vacation a month later. While in San Diego, the Laughlins were likely introduced to Gill's work, if not Gill himself, in the off chance they had not previously met in Los Angeles. ("Society: Are at Coronado," (LAH), August 2, 1907, p. 5). If not during their Coronado vacation, Gill could well have met Laughlin while visiting Albright at his Laughlin Building office or at one of Albright's many lectures, or possibly even during the construction of the Laughlin Building Annex in 1905. It also seems plausible that Albright, with more work than he could handle and having a preference for large commercial projects over residential design, may have referred Laughlin to Gill as a payback of sorts for being awarded the U. S. Grant Hotel commission. In any event, it was sometime around January 1908 that Laughlin commissioned Gill to begin design on his first solo Los Angeles project. ("Laughlin to Build New Residence; Will Be Model of Modern Construction," LAH, February 8, 1908, p. III-6. ("Building is Active," LAH, June 8, 1902, p. IV-1). (Author's note: Gill and Albright both had work on display in the Los Angeles Architectural Club's second annual exhibition in the Associated Arts Hall in May 1908, a few months after Gill landed the commission for the Homer Laughlin, Jr. house. ("Los Angeles Architectural Club's Annual Exhibition," Architect and Engineer, July 1908, p. 61).

Homer Laughlin, Jr., who graduated with a degree in chemical engineering from Stanford in 1896, likely first became attracted to the properties of reinforced concrete while watching with great interest the construction progress of Albright's Laughlin Building Annex. When it came time to choose an architect for his own personal residence, he selected Gill, who used concrete and hollow tile for the two-story, 11-room residence at 666 W. 28th St., described in detail earlier. Gill and Laughlin arranged with architect Albert Walker to receive bids for the project while Gill was attending to business in San Diego. Walker's office was located next door to Laughlin's on the 6th floor of the Laughlin Building, one floor above Albright's offices. ("Architects Are Busily Engaged; Many Magnificent Homes Are Being Planned," LAH, April 19, 1908, p. IV-2).

("Eight-Story Building to Cost $250,000," LAH, April 12, 1908, p. III-7).

Ironically, the same week bids were being received on Gill's Laughlin house Albright was also receiving bids in his Laughlin Building office for an 8-story office building at the corner of 6th and E Streets in San Diego he designed for future Gill client Henry H. Timken, inventor and patent holder of the tapered roller bearing and many other parts used in the burgeoning automobile industry (see above and later below). (Ibid). Timken's wife passed away in late 1908, followed by Timken himself in early 1909 while the Timken Building was under construction. ("Millionaire Carriage Manufacturer Expires," LAH, March 17, 1909, p. II-2). Henry Timken, Jr., came from the Midwest to settle his father's affairs and met Albright and, through hi,m Laughlin and Gil,l which would result in Timken Jr. commissioning Gill to design a house at 335 Walnut Ave. around the corner from his father's estate at 3430 4th St. in July 1911. (This is discussed in more detail in Part II.)

Henry H. Timken, date and photographer unknown. From Wikipedia.

Gill must have been intrigued by the fact that while designing Laughlin, Jr.'s house, his client joined forces with Albright and a group of prominent Los Angeles businessmen to file articles of incorporation for the creation of the Victor Portland Cement Company in Victorville. It was a serious attempt to profit from the shortage of, and boom in the use of reinforced concrete as a construction material, and save on exorbitant Portland Cement shipping costs. The group was also certainly cognizant of the growth potential of Los Angeles, which would inevitably be spurred by the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct and the Panama Canal. While his house was under construction Laughlin, Jr. and Albright were among a group of fifty local businessmen to visit the plant site. Gill was possibly among the group. ("Cement Company Files Articles of Incorporation," LAH, March 24, 1908, p. II-5 and "To Inspect Cement Plant," LAH, June 28, 1908, p. II-5). (Author's note: This may have planted the seed or provided the inspiration for Gill to incorporate his own Concrete Building and Investment Company in 1912. For much more on this, see my "Sarah B. Clark Residence, 7231 Hillside Ave., Hollywood, Spring 1913: Irving Gill's First Aiken System Project").

Department of Water and Power Cement Plant, aka "Monolith," Mojave. William Mulholland, 1909. From Water and Power Associates.

William Mulholland (see below) was then nearing completion of the Department of Water and Power's own plant in Mojave to supply lower-cost cement for the aqueduct (see above). A new plant was also then being constructed in Riverside which would become the Riverside Portland Company after its completion in late 1909. (Author's note: Homer Laughlin, Jr. and William Mulholland were active members of the Seismological Society of America in the early 1920s and were likely acquaintances long before that.).

William Mulholland portrait by soon-to-be Gill client George Steckel. From Moody, Charles Amadon, "Los Angeles and the Owens River," Out West, October 1905, p. 424.

Van Nuys Hotel, 4th and Main Streets, 2 blocks east of the Laughlin Building. Morgan and Walls, architects, 1897.

After the completion of the Laughlin House, Gill visited Los Angeles to attend the tenth semi-annual California Promotion Committee meeting held at Blanchard Hall, a half block north of the Laughlin Building. While visiting Los Angeles, Gill's hotel of choice was the Van Nuys (see above), located two blocks east of the Laughlin Building. Besides Gill, the San Diego delegates among the 500 in attendance included his 1904 clients Julius Wangenheim and E. M. Barber, his 1907 client Wheeler J. Bailey, current client Edward W. Scripps (Scripps Institute) and future 1911 client Jared Torrance (Industrial City of Torrance) and Harrison Albright's clients U. S. Grant, Jr. and H. L. Titus (Coronado Beach House). ("Promoters of California's Welfare Here," LAH, November 14, 1908, p. 12. (Author's note: Most of this same San Diego group were likely in attendance at the Committee's sixth meeting at the Coronado Hotel two years earlier (see below)).

Delegates to the sixth meeting of the California Promotion Committee, Coronado Hotel, San Diego, December 15, 1906.

Bishop's Day School, 3012 1st St., San Diego, 1909.

Ellen Browning Scripps, n.d. From Shragge, Abraham J. and Kay Dietze, "Character, Vision and Reality: The Extraordinary Confluence of Forces that Gave Rise to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography," San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Summer 2003.

Even though Gill had no Los Angeles projects in 1909 he spent considerable time there attending A.I.A. meetings and conferring with Bishop Joseph H. Johnson (third from right below) and patron Ellen Browning Scripps on the design of his Bishop's Day School in San Diego (see above) and Bishop's School for Girls in La Jolla on land donated by Scripps. Gill was also busy on the design plans for the Scripps Biological Station during this period. ("Bishop Johnson Buys Site for New School," LAH, April 15, 1909, p. 5 and "New Concrete Structure," LAH, March 21, 1909, p. II-5).

Formal dedication of Scripps Institution, 1916. Attending the ceremony, from left to right, were Dr. E. W. Ritter, D. T. MacDougal, David Starr Jordan, Bishop Joseph H. Johnson, Prof. G. H. Packer, and Benjamin Ide Wheeler. (From Shragge and Dietze).

Scripps Biological Station, La Jolla, 1908-10. From Hines, p. 137.

Johnson also frequently commuted to San Diego to sign contracts, check on the construction progress of the Day School, and consult with Gill and Scripps on the design plans for the La Jolla boarding school (see below). Although it is possible Gill and Johnson met through the Laughlins as they traveled in the same social circles, it is much more likely that Gill's and Johnson's mutual patron, Ellen Browning Scripps, made the initial introduction and selection of the architect. (Author's note: Bishop Joseph Horsfall Johnson was the father of architect Reginald D. Johnson, whose first project was his father's 415 S. Grand Ave. house in Pasadena in 1910.).

Bishop's School for Girls, La Jolla. Scripps Hall, 1910, on the left. Bentham Hall, 1912, on the right.

"Exhibition of the Los Angeles Architectural Club," Architect & Engineer of California, February 1910 cover.

Mrs. Arthur Marston House, San Diego, Irving Gill architect. From Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club, 1910.

A presentation rendering of Gill's Arthur Marston House (see above) was exhibited in the fourth annual Architectural Club of Los Angeles exhibition in February of 1910 in the Hamburger Building along with Albright's Spreckels Theater Building and San Diego Union Building where he finally established a San Diego office the same year (see below). (Ibid). Thus it seems plausible that Gill and Albright could have been comparing notes on ongoing developments in reinforced concrete construction techniques. Gill also broke ground for Scripps Hall at the Bishop's School for Girls, the same month. ("School and Colleges: San Diego," SWCM, February 12, 1910, p. 9).

Yearbook: Los Angeles Architectural Club, 1910.

Riverside Portland Cement Company Plant, Crestmore, 1909. From Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer (SWCM), November 20, 1909, p.

Gill was most likely in attendance at the April 1910 AIA meeting in Los Angeles when it was announced that the group had accepted an invitation to tour the recently completed Riverside Portland Cement Company Plant in Crestmore near Riverside on May 7th (see above). In Los Angeles most likely meeting with clients Homer Laughlin and Fred B. Lewis, Gill definitely attended the May 1st joint Northern and Southern California AIA chapter meeting. ("Joint Meeting of Northern and Southern California Chapters, A. I. A.," Architect & Engineer of California (A&E), May 1910, p. 57).

Being listed as a new member of the Southern California Chapter in June is a good indication that Gill also attended the cement plant tour the previous month. Having recently contracted with Gill to design a garage for his father's residence, Homer Laughlin, Jr., might also have attended despite no longer being involved in the Victor Portland Cement scheme, although Albright still was. ("Cement Company Reorganized," Cement and Engineering News, December 1909, p. 112)

First Homer Laughlin, Sr. residence after moving to Los Angeles in 1896, second from left, 894 S. Bonnie Brae St. Architect and photographer unknown. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Homer Laughlin, Sr. Residence, 666 West Adams Blvd., 1897, F. L. Roehrig, architect. Purchased by Laughlin in 1901. (For much more on Roehrig, see my "Frederick L. Roehrig, The Millionaire's Architect").

Sometime in the spring of 1910, Gill received his second solo Los Angeles commission, this time for a substantial garage for automobile enthusiast Homer Laughlin, Sr., at his residence at 666 West Adams Blvd., two blocks south of his son's house near the USC campus. As a long-time friend of fellow Ohioan William McKinley, Laughlin, Sr. proudly led the reception committee at the same West Adams family home (see above and below) during the President's visit to Los Angeles in the spring of 1901, not long before his assassination in Buffalo later that year. ("Brilliant Reception for the President; Mr. and Mrs. Homer Laughlin the Hosts," LAT, May 10, 1901, p. I-6).

Homer Laughlin, Sr. residence living room, 666 West Adams Blvd. (Ibid).

"No Horses Downtown; Homer Laughlin Says Autos Will Supplant Them," LAT, February 14, 1904, p. II-3.

Laughlin, Sr. was a charter member and officer of the Automobile Club of Southern California and proudly showed off his 1904 White Model D for a period, Los Angeles Times article (see above) in which he extolled the virtues of the automobile. He was heavily quoted on such subjects as Southern California's preeminence as a locale for good motoring, the need for good roads to maintain that preeminence, the importance of automobile racing in advancing improvements to the automobile, Automobile Club activities in the promotion of better roads, and the future of motor-powered machines to revolutionize such areas as agriculture. (Author's note: Laughlin, Jr. would later act on his father's prescience by developing his own automobile and tractor company as discussed later below.).

"Southern California is second to no section of the United States in adaptability for the driving of the automobile, and she will have to do something in the near future or lose that which is becoming the greatest drawing card with the wealthier class of Eastern people, people who spend a portion of every year in search for that clime which will afford them the greatest amount of outdoor recreation and bodily comfort..."

Laughlin said of the layman's view of the automobile, "At present the general public does little else but slur the automobile as "the red devil of destruction." If people want good roads let them cease their outcry against the automobile for through that agency good roads will be obtained." (Ibid).

1904 White Model D is typical of the one owned by Laughlin.

When asked if he believed in auto racing, Laughlin opined,

"Most emphatically I do. Not in the racing of novices along the country road or through the city streets, but in the racing of the automobile as a test on special speedways by men who are masters of their machines. In no case should racing be allowed in the city, and with the provision of speedways either inland or on the seashore built especially for that purpose." (Ibid).

"Beach Races at Coronado, Local Cars Enter for Big Auto Event There," LAT, February 19, 1905, p. III-3.

Laughlin's precious comments foresaw the sponsorship of a big "benzene buggy enthusiasts" event on Coronado Beach the following February, sponsored by the Hotel Del Coronado and soon-to-be Harrison Albright client John D. Spreckels (see above). Los Angeles entrants competing for the Spreckels Trophy included fellow Automobile Club members Frank Garbutt and M. T. Hancock. (Inkersley, Arthur, "Automobiling," Western Field, October 1903, p. 638. Author's note: John D. Spreckels also owned a White touring car and possibly knew the Laughlins by this time. For much more on early Auto Club members and their activities, see my "Playa del Rey, Speed Capital of the World. (Author's note: Ironically, the Headquarters of Automobile Club of Southern California at Adams and Figueroa has expanded to incorporate Laughlin, Sr.'s property.).

Kindred, avid automobile buffs, Laughlin, Jr., and Sr. worked with Gill on the design for Sr.'s considerable $5,000 two-story reinforced concrete garage project for which the building permit was issued in early July. Laughlin, Jr., was listed as the builder on the permit. By 1910, Laughlin, Sr. had become the proud owner of a brand new Lozier Landaulet (see below); thus, the garage was likely outfitted as a state-of-the-art auto repair shop, as was Laughlin, Jr.'s nearby garage. No plans or photos have been found as yet for this project. (Inkersley, Arthur, "Automobiling," Western Field, August 1903, p. 497. "Building Permits," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, July 9, 1910, p. 25).

"Announcement of 1911 Line of Lozier Motor Cars," Horseless Age, August 17, 1910, p. 226.

Laughlin, Jr. also ordered a new 1911 Lozier Lakewood Model for his 1908 Gill-designed garage after experiencing his father's car on an extended trip of the Northeastern states the family took in late summer while Laughlin, Sr.'s Gill-designed garage was under construction. The Laughlins were also undoubtedly proudly following the success of the Lozier brand on the racing circuit, especially at the Los Angeles Motordrome owned by fellow Auto Club member and vice-president Frank Garbutt (see below for example). ("Gossip Along Gasoline Row," LAT, September 11, 1910, p. VII-3 and "Playa del Rey, Speed Capital of the World").

"Lozier Racing Car Holds Many Records for Speeding," San Francisco Call, March 2, 1911, p. 8.

Roorbach, Eloise, "A New Architecture in a New Land," The Craftsman, August 1912, p. 468.

Shortly after Gill received the Laughlin garage commission, Fred B. Lewis contracted with him to design 12 rental units at the corner of Alegria and Mountain Trail Streets in Sierra Madre. Lewis received bids for the project while Gill was beginning work on the Laughlin garage. Each concrete and hollow tile unit for the $30,000 project contained a large living room, buffet kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom, with all units surrounding a large central courtyard garden (see above and below). ("Residences," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, July 23, 1910, p. 12).

Roorbach, Eloise, "A New Architecture in a New Land," The Craftsman, August 1912, p. 467.

Gill liked what he was learning from his Los Angeles colleagues and wanted to spread it to his home base. Meeting in Gill's office in early September, a slate of officers was elected. Gill's former partner, William S. Hebbard, the reigning dean of San Diego architects and 1901 charter member of the State Architectural Board of Certification, was named President, S. G. Kennedy - Vice-President, Gill - Secretary, and Charles Quayle - Treasurer. Gill's field superintendent Richard Requa and others attended the meeting. ("San Diego Architects Organize," SWCM, September 3, 1910, p. 26).

Under the auspices of the new group, Gill soon led the charge, recommending that the San Diego Building Department be reorganized to be under a single head who is a certified architect or engineer, modeling itself along the lines of the City of Los Angeles, whose building department Gill had recently studied. ("Ask Reorganization of San Diego Building Department, SWCM, November 12, 1910, p. 17. For much on Gill's role in organizing San Diego's architects and his efforts to improve the San Diego Building Codes see Schaffer, Sarah J., "A Significant Sentence Upon the Earth: Irving J. Gill, Progressive Architect Part II: Creating a Sense of Place," Journal of San Diego History, Winter 1998.).

Verso of Steckel portrait ca. 1907. From internet.

During September, Gill was working on the plans for a substantial 2-story 12-room house for the well-decorated dean of Los Angeles society portrait photographers, George Steckel (see awards above for example). Steckel's studio and art gallery were located on the entire fifth floor of the Gray Building at 336 1/2 S. Broadway, across the street from the Laughlin Building, after he moved from 220 S. Spring Street in 1908. Steckel's gallery served as the temporary exhibition space for the Fine Arts League of Los Angeles, which was incorporated in 1907 with the intended purpose of forming Los Angeles's first fine art museum. The League's vision was achieved with the opening of the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History, Science and Art in Exposition Park in early 1913. ("Los Angeles Fine Arts League Holds Its First Exhibition at Steckel Gallery," LAH, April 4, 1909, p. II-7 and "Fine Arts League: Organization for Advancement of Permanent Museum Announces Near Completion of Building," LAT, September 24, 1912, p. I-12. For much more on the organization and management of the new museum and its associated Otis Art Institute, see my "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association".

Homer Laughlin, Sr, ca. 1909. Portrait by George Steckel. Moody, Charles Amadon, "Makers of Los Angeles," Out West, April 1909, p. 373.

Front elevation, George Steckel Residence, Normandie Ave. near 4th St., Los Angeles, 1910. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

The front facade of the Steckel Residence (see above) expressed similarities with the Laughlin House, sans the pitched roof. The commission likely came about through a Steckel acquaintance with Laughlin, whose portrait he took for a 1909 article in Out West (see two above). (Author's note: Photographer Edward Weston briefly worked for Steckel shortly after his 1908 arrival in Los Angeles from Chicago. Weston's close friend Johan Hagemeyer also worked for Steckel for a short time in 1918-19 after a brief apprenticeship with Weston. (Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, Getty, 2011, pp. 9-10, 138, 153.

First floor plan, George Steckel Residence, Normandie Ave. near 4th St., Los Angeles, 1910. Courtesy of UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Irving Gill Archive.

Gill arranged for the Steckel House bids to be received by Los Angeles architect E. C. Kent, whose name also appeared along with Hebbard and Gill on their preliminary drawing of the U. S. Grant Hotel shown earlier above. Kent's office was two blocks from the Laughlin Building at 427 W. 5th St. Despite a building permit being issued for Steckel's lot on Normandie Ave. near 4th St., the house was not built. Steckel would, a few years later, construct a house and studio designed by someone else on land he purchased among the orange groves of Covina. ("Building News: Los Angeles Notes: [George Steckel] Residence," SWCM, October 1, 1910, p. 9.)

U. S. Grant Hotel, Wilde Fountain, and Horton Plaza ca. 1915. From the San Diego History Center.

Through his connections with Marston and the fact that Gill had designed a house for Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.'s brother Albert in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1901, he had high hopes of being named the chief architect for the Exposition. Likely for future business reasons, the Olmsteds preferred to collaborate with the more familiar and prominent East Coast architect Bertram Goodhue and successfully lobbied for his selection. (See numerous early 1911 letters referencing Gill in the Olmsted Papers in the Panama-California Digital Archive.)

Front elevation and pergola, Paul Miltimore House, 1302 S. Chelton Way, South Pasadena. Photo by the author, February 2015.

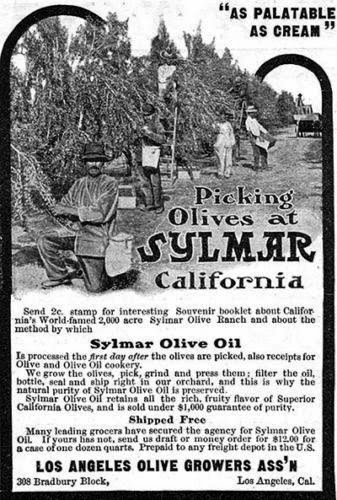

Los Angeles Olive Growers Association Orchard, Sylmar, California, 1911. Baltimore, J. Mayne, "World's Largest Olive Orchard," Technical World Magazine, July 1911, pp. 538-40.

Los Angeles Olive Growers Association ad. The Delineator, January 1902, p. 182.

There are strong indications that Gill's Miltimore commission may have come about through Paul Miltimore's and/or her stepdaughter Catharine's friendship with the Laughlins. After her husband's passing, Paul became vice-president and step-daughter Catharine secretary of the Los Angeles Olive Growers' Association, whose office was for a time in the Bradbury Building (see below) directly across the street from the Laughlin Building. Catharine Miltimore and Homer Laughlin, Jr.'s wife, Ada Edwards Laughlin, were also fellow alumnae of the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority and served together on the organization's National Scholarship Committee. (1911 Los Angeles City Directory and Kappa Alpha Theta, L. Pearle Green, editor, Volume 24, 1909-1910).

Bradbury Building, southeast corner of Broadway and 3rd St., 1893. George Wyman, architect. From Water and Power Associates.

Backyard, Paul Miltimore Residence, South Pasadena. Kamerling, pp. 82-83.

Living room and dining room, Paul Miltimore Residence, South Pasadena. Kamerling, pp. 82-83.

Miltimore House, first floor plan. From Hines, p. 117.

Paul Miltimore Residence, second floor plan. From Hines, p. 117.

Lloyd Wright, ca. 1910. From Hines, p. 232.

Nursery, Balboa Park, ca. 1911.

It was sometime in early 1911 that new Olmsted Brothers employee Lloyd Wright, with cello in tow, moved to San Diego to work as a nurseryman-draftsman on the Panama-California Exposition project shortly before his father's earlier-mentioned Wasmuth Portfolio would be published in Europe. Upon returning to the U.S. after some post-portfolio European travel with Taylor Woolley and a brief stint at the Harvard Herbarium, the aspiring landscape architect found work with the Olmsteds in Boston. Lloyd was soon asked to join John C. Olmsted and associate partner James Frederick Dawson in San Diego. Olmsted and Dawson were staying in Albright's newly opened U. S. Grant Hotel.

Out West, October 1912.

Tending the nursery and helping with the initial planting in Balboa Park (see above and below), Lloyd listed himself in the 1911 San Diego City Directory as living in the Elk Apartments at 1665 9th St. (see below) and his occupation as gardener. (Author's note: The 1912 Directory listed Lloyd as a draftsman for Irving Gill and his brother John, by then living with him at the above address, as a draftsman for Harrison Albright).

Elk Apartments, 1665 9th St., San Diego. From Google Earth.

Louis Gill, 1911. Photographer unknown. From Kroll, Rev. C. Douglas, "Louis John Gill: Famous But Forgotten Architect," Journal of San Diego History, Summer 1984, p. 152.

Recent architectural school graduate Louis Gill (see above) moved into his uncle's home at 3719 Albatross Street (see below) and joined his office sometime in the fall of 1911. With his uncle's connections Louis wasted no time in obtaining his architectural license by the end of 1911. ("Municipal and State Engineering: New Architects," Architect and Engineer of California, December 1911, p. 106).

Irving Gill Cottage, 3719 Albatross St., San Diego, Irving Gill, architect, 1908. Photo by the author, May 16, 2015.

This concludes Part I. Part II will begin with Gill's involvement with the new Industrial City of Torrance and continue through 1916.

.jpg)