(Click on images to enlarge.)

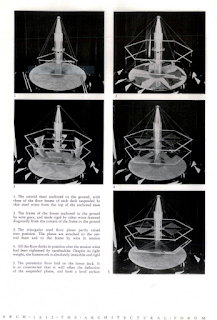

Buckminster Fuller and his model of the Dymaxion House, ca. 1930. Photographer and place unknown.

Left: Stockade Building System, 103 Park Ave., New York, 1927. Right: Stockade Patent, James Monroe Hewlett and Richard Buckminster Fuller, June 28, 1927. After a stint in the U.S. Navy between 1917 and 1921, Buckminster Fuller and his architect father-in-law, James Monroe

Hewlett, joined forces in 1922 to form a company that used a compressed fiber block invented by Hewlett to create

modular houses using the Stockade Building System. Hewlett was a well-connected architect who was past president of the New York Architectural League from 1919 to 1921. Hewlett and Fuller received a patent for the system in 1927. (See above right.).

Examples of houses built using the Stockade Building System from the above marketing brochure. Ibid., frontispiece and back cover of the above left Stockade Building System brochure.

Stockade Building System strength test performed at M.I.T. in 1924 from Becoming Bucky Fuller by Loretta Lorance, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2009, p. 20.

Fuller worked indefatigably to develop the right formula mix for block manufacture and strength-testing of the materials, while Hewlett worked on attracting investors and setting up a corporate structure. Fuller also assisted Hewlett in the marketing of the new building system. Fuller was finally rewarded with the leadership of the Stockade Midwest Division in Chicago by the end of 1926.

Left: "The Stockade System of Building," American Architect, January 1926, p. 81. Right: "Blocks of Straw Yet Houses of Reinforced Concrete," Scientific American, May 1926, p. 331.

Hewlett's architectural connections likely brought Stockade to the attention of the editors of The American Architect, who were planning a fifty-year "Golden Anniversary" issue for January 1926. Benjamin Betts informed Fuller that "in the preparation of historical data on the development of the building industry during the last fifty years...1875 to 1925... we are writing companies like your own, who manufacture construction materials." A brief article in the May 1926 issue of Scientific American also helped to build credibility in the fledgling system. (B. T. Betts, New York, to RBF, New York, June 1, 1925, Chronofile, Vol. 25 (1926-1926, Lorance, p. 22.

Left: Stockade Building System, Exhibition of Stockade Wall System from Lorance, p. 30. Right: Stockade Residence at Joliet, Illinois, ca. 1926, Ibid. p. 31.

In three and a half years, Stockade licensed four subsidiaries and built three block manufacturing factories, including one in Joliet spearheaded by Fuller. Hewlett developed financial difficulties in 1927, forcing him to sell some of his shares in the company and thus lose control to a new owner, which ultimately resulted in Fuller's ouster in the new corporate restructuring. Fuller's continuing involvement with troublesome, conflicting patents with a former fellow Stockade employee finally drew to a close in the spring of 1928. From this point on, Fuller focused all his energies on his 4D house vision. (Lorance, pp. 38-41).

Left: 4D Time Lock by Buckminster Fuller, 1927. Right: Model of 4D House, aka "Dymaxion House," designed by Buckminster Fuller, 1928. Right: 4D House, United States Patent Office file no. 1,793, submitted April 1, 1928. Buckminster Fuller, inventor.

On May 16, 1928, the A.I.A. opened its annual convention, and that is where Fuller first introduced his 4D House idea by distributing dozens of his mimeographed copies of his 40-page essay "4D Time Lock," essentially a business proposal explaining his plan for a new style of affordable housing. In it, he wrote, "These new homes are structured after the natural system of humans and trees with a central stem or backbone, from which all else is independently hung, utilizing gravity instead of opposing it. This results in a construction similar to an airplane, light, taut, and profoundly strong." It was signed under what would become his professional name: R. Buckminster Fuller. Unfortunately, Fuller's efforts made little, if any, impact. (From "The Art Story-Buckminster Fuller").

After returning from the convention Fuller sent off most of the remaining copies of "4D Timelock" to dozens of influential people including Paul Frankl, Barry Byrne, Russell Walcott, Henry Ford, Thornton Wilder, Claude Bragdon, Bertrand Russell, John Galsworthy, and many major city newspaper and architectural journal editors and industrialists including ingratiating creative hooks in his introductory letters intended to increase his rate of response. One of the letters began, "Last week it [4D Timelock] was presented to 18 members of the American Institute at St. Louis, who were picked out as being broad and unselfish thinkers, and with more than satisfactory results." He also sent a copy to his father-in-law, James Monroe Hewlett, who was by then vice-president of the A.I.A., who responded thusly,

"I have been trying to get time to write to you ever since I

got back from St. Louis but found things rather piled up. 1 have read your

pamphlet very carefully and it seems to me that you are starting on a perfectly

logical idea but one which involves a greatly improved solution of a great

number of detailed problems before you would possibly be in a position to say

“go” on a quantity production basis.

If you have the backing necessary to engage in the

experimental construction in the many different fields that must be covered, it

would seem to me that it would be wise to go slow on the exploitation of the

idea until you are ready to follow it up with something far more definite than

the general statements contained in your pamphlet.

I should be very much interested to see any plans or more

detailed description of the way you expect to solve these problems and of the

materials you expect to use as it is on such points as these that any

architect’s suggestion would be likely to be helpful.

Love to all." (To R.B.F. from J. Monroe Hewlett of Lord & Hewlett, Architects, 2 W. 45th St., New York City, June 4, 1928).

After a second, more explanatory letter from Fuller, Hewlett responded again in July.

"I am returning herewith the information you sent me in

regard to the patents-, applications, etc., as I do not think there is any

likelihood that I can contribute any useful ideas unless I get a great deal

more time than at present seems to be available to think over the matter. Granting the economical soundness of the basic idea which I

certainly do grant I am rather appalled by the number of supplementary matters

in regard to which some solution will be necessary before making an actual

plunge into production but that of course is a matter that you have been giving

constant thought to and those things when they are put into the form of a

complete schedule sometimes appear less formidable than when simply thought

about. I shall be interested to hear further of your plans as they

develop and, also, whether the backing that you are relying upon is in your

judgment sufficient to tide you over what must necessarily, I should think, be

a long period of experimentation and promotion." (To R.B.F. from J. Monroe Hewlett, New York City, July 9, 1928). From Buckyverse.

The unabashed Fuller also sent a copy to Dr. A. Lawrence Powell, President, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass..

"As the fifth generation of Harvard men (my father and

grandfathers having been in the classes of 1740, 1801, 1843, 1883, and, though

of unenviable scholastic record, myself, none the less a proud member of the

class of 1917) the writer in deep earnestness asks that you immediately read

the attached paper, making a suitable comment. The expediency of the

multi-letter is obvious and its informality inconsequential." (From BuckyVerse, "4D Timelock").

Within this period, Fuller also organized a "4D class" of bright, young Chicago architects to help him develop his patent design and build his first model. In a letter to his friend, French architect Paul Nelson, describing the class Fuller wrote,

"The leader ... is Leland Atwood, 27 years old, artist and draftsman. He has studied at the University of Michigan....Others...are Robert Paul Schwiekher, 25...who won the scholarship of the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club, which sent him to Yale University Architectural School...Another is Clair Hinkley, 30...who attained the highest marks at the Armour Institute School....A young member is...Tad E. Samuelson, honor student of the Armour Institute." (RBF to Paul Nelson, sailing from New York to Paris, August 11, 1928, Chronofile, vol. 36 (1928) from Lorance, pp. 164, 166). (Author's note: Leland Atwood and Paul Schweikher were at one time both chief draftsmen in the office of George Fred Keck and were involved in the designs of both the "House of Tomorrow" in 1933 and the "Crystal House" in 1934 at the Chicago World's Fair.).

Left: Interior drawing of Dymaxion House by Lee Atwood, February 1929, from Becoming Bucky Fuller by Loretta Lorance, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2009, Plate 7, p. 130. Right: Postcard for Le Petit Gourmet Restaurant, 615 N. Michigan Ave., Chicago. Date unknown. From eBay.

Fuller sent another ingratiating introductory letter to novelist and poet Jean Toomer with a copy of "4D Timelock" on Jun 15th, in which he suggested, "We might arrange supper, or lunch, or a walk. I walk the length of Lincoln Park at least once a day," Toomer responded enthusiastically on the 17th, "I have an increasing interest in your whole idea and work." (Nevala-Lee, p. 114).

Toomer was able to arrange the first-ever private showing of a model of the 4D House in September 1928 at Le Petit Gourmet Restaurant on North Michigan Avenue in Chicago. (See above right.). A sketch of the "Hexagonal House" was also shown in the restaurant and published in the local paper. (See above and "Tree-Like Style of Dwelling Planned," Chicago Evening Post, December 18, 1928).

Marshall Field's Invitation, Dymaxion House Lecture Announcement, April 6-20, 1929.

After an exhibit and lecture at the studio of Rudolph Weisenborn Fuller next landed an exhibition at Marshall Field's flagship department store on State Street, where, according to Fuller, the retailer had received a consignment of modernist furniture from Europe, which it hoped would seem less radical in comparison with his house. Field's advertising manager Waldo Warren coined the name "Dymaxion" for Fuller's 4D House as a combination of the terms taken from Fuller's presentation, i.e., "dynamism, maximum, and tension." Fuller loved the name and has used it ever since. Beginning on April 6th, Fuller lectured at Marshall Field's Interior Decorating Galleries six times a day for the next two weeks. He later claimed that Chicago modern architects George Fred Keck and Howard Fisher had been inspired to start housing projects of their own after hearing him speak. (Nevala-Lee, p. 116. And also "Builds Unique House to Sell by the Ton," Chicago Herald & Examiner, April 13, 1929. Author's note: I his Chicago Art Institute oral history, architect Bertrand Goldberg remembered attending a four-hour Buckminster Fuller lecture at Rudolph Weisenborn's studio.

Left: "Dymaxion House Has Ultra Design," Washington Evening Star, April 26, 1929, p. 5. Right: "Not Before the Mast, but Around It, Pneumatic House, Built Like a Tree," Christian Science Monitor, Boston, May 23, 1929, p. 4.

Fuller tried the annual A.I.A. convention again in May of 1929, this time in Washington, D.C., where he at least garnered some newspaper publicity with a 700-word article in the

Evening Star.

(See above.). At the convention, he also chanced to meet Harvey Wiley Corbett, the head of the architectural committee for the upcoming 1933 Chicago World's Fair, and, after talking to Corbett, felt confident that his Dymaxion House would end up being selected to be displayed at the fair.

(Inventor of the Future by Alec Nevala-Lee, Dey St., New York, 2020, p. 116).

"The Wonder City You May Live to See" by Harvey Wiley Corbett, Popular Science Monthly, August 1925, pp. 40-1.

If, perhaps by chance, Fuller had seen Corbett's 1925 article "The Wonder City You May Live to See" (see above), he would have been extremely encouraged. After perusing Fuller's 4D Time Lock at the A.I.A. convention, Corbett likely saw in Fuller a fellow futurist and encouraged him in his ongoing efforts to market his idea by offering him space in his own offices to fine-tune his drawings. (Nevala-Lee, p. 126).

The architectural journal Pencil Points published a review of the 1929 A.I.A. Convention activities, including a few paragraphs on Fuller's "Dymaxion" House:

"...for example, designed and patented by Buckminster Fuller, the model on exhibit in room 563, was a most ingenious and ingenuous contraption, calculated to upset all established theories of building. The materials are duralumin, and piano wire and everything is in tension, automatic and pneumatic. No description can do it justice, certainly it takes a lot of explaining, but its appearance calls to mind the limerick concerning the invention of a certain young man from Racine. We suggest a post-graduate course in the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design for Mr. Fuller, so that he may soften and humanize his mechanical nudities. We were so upset over the Dymaxion House that we left the morning session hurriedly, even forgetting to return till late in the afternoon." ("Tale-Lights of the A.I.A. Convention," Pencil Points, June 1929, pp. 405-408).

Left: Statement of Purpose and Membership Form for the Harvard Society For Contemporary Art, 1928. (Weber, p. 28). Right: John Walker, III, Lincoln Kirsten, and Edward M. M. Warburg, the founders of the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. (Weber, p. 5).

The following month, the tireless Fuller accepted an invitation from the recently formed.

Harvard Society for Contemporary Art for their fourth ever exhibition, just two months after being formed. Twenty-two-year-old Lincoln Kirsten and Edward Warburg, age eighteen (both in their junior year at Harvard), started the organization, which was housed in two

small rooms on the second floor of the

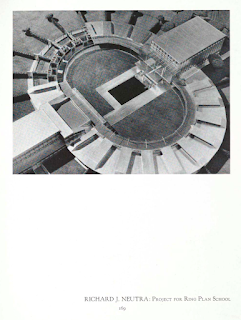

Harvard Cooperative Building at 1400 Massachusetts Avenue across from Harvard Square. Future 1936 Richard Neutra client John Nichols Brown headed a prestigious list of the organization's trustees, along with Harvard Museum director Paul Sachs and Edward Warburg's father, Felix.

(See HSCA letterhead above left.).

Fuller's exhibition "Richard B. Fuller, 4D - Dymaxion House," which ran from May 20th to 24th, was an important return to Cambridge where the former Harvard student reportedly displayed his model to numerous professors as well as to a senior named Philip Johnson, who was intrigued by Fuller's showmanship and use of aluminum - the basis of his family's fortune.

"Unique Dynamic House, Arborial Design, Solve Dwelling Problem," Harvard Crimsom, May 21, !929, "Dymaxion," Ibid., May 22, 1929, "Dwelling of Tomorrow Suspended Around Central Mast, Boston Traveler, May 21, 1929, " "Not Before the Mast But Around It," Boston Post, May 23, 1929, "Visions Modern Home Circular and High, Chicago Evening American, May 23, 1929, "Six Sided House Hung From Mast is Latest Model, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 23, 1929, p. 4, "Twice "Fired" Harvard, Returns Startle Profs with Hanging House" by Victor O. Jones, Boston Globe, May 25, 1929, and artist-info Blog).

Left: Descriptive flyer for "The Dymaxion House" by Buckminster Fuller, Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, May 20-24, 1929, Harvard Cooperative Building, Cambridge. (Original printed on bright lemon yellow paper printed in gaudy valentine red. (Weber, p. 62). Right: Buckminster Fuller with model of his Dymaxion House, photograph from "Hangs His House From a Mast," Boston Globe, May 20, 1929. (Ibid., p. 63).

Before the exhibition, the executive committee sent out formal invitations to selected invitees, which stated,

"This house, built like a tree, with inflatable doors and floors, can be sold for $500 dollars a ton on a mass production basis ... We would appreciate you telling whomever else you think would be interested and bringing them here to the rooms."

Left: Philip Johnson by Carl Van Vechten, ca. 1932. (Weber, p. 67). Right: "Not Before the Mast, but Around It," Christian Science Monitor, Boston, May 23, 1929, p. 4.

At the exhibition, Fuller conducted two one-hour lectures each morning and two each afternoon, and a three-hour lecture each evening. Johnson had not previously met any of the Harvard Society fellows; he simply stopped in to see the Dymaxion exhibit because it was there, and it was new and exciting.

"Johnson had a vested interest in Fuller's use of aluminum. Homer Johnson, Philip’s father, was a lawyer who had done the patent work for the process to make that new substance, and had taken his legal fees in the form of stock in the company that was to become ALCOA. In 1926, Homer had turned those stock shares over to Philip. But whether or not it was financial concern that drew Philip Johnson in to Fuller’s exhibition, it made “an indelible impression” on him. “That Dymaxion House, I disliked it very much, but that made no difference. You see the point is . . that [from it] I learned vast amounts of the potentialities of architecture that I never forgot."

(Weber, p. 68. Author's note: Johnson himself, three years later would co-curate with Henry-Russell Hitchcock "Modern Architecture, International Exhibition" at New York's newly formed Museum of Modern Art which included work by Kocher and Frey and Richard Neutra whom he also had his father hire to design aluminum bus bodies in Cleveland, Ohio. See much more at my "A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, Richard Neutra, R.M. Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright, Albert Frey and the Evolution of Modern Architecture in New York and Southern California")."

Theodore Morrison published a 5000-word article, "The House of the Future," in the September issue of House Beautiful, in which he referenced Fuller's May exhibition in Cambridge:

"A visitor to the Cambridge meetings can testify that Mr.

Fuller held in complete absorption a crowded roomful of people, many of them

standing, for an hour and a half while he exhibited his models and explained

their structure and significance. His hearers listened in delight, applauded

when he had finished, and stayed to ask questions." (See below).

("The House of the Future," by Theodore Morrison, House Beautiful, September 1929, pp. 292-3, 324, 326, 328, 330).

("The House of the Future," by Theodore Morrison, House Beautiful, September 1929, pp. 292-3, 324, 326, 328, 330). Isamu Noguchi had received a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Paris in 192,7, and the quality of his work qualified him for a renewal of his fellowship for 1928. ("Art Fellowships Awarded," New York Times, May 10, 1928, p. 26).

Piece recently exhibited in Paris by Isamu Noguchi from "Paintings and Sculpture Shown in Paris," by Ruth Green Harris, New York Times, March 31, 1929, p. 113. Piece identified as "Face Form," 1928, at Noguchi Archive.

Noguchi then made a big splash upon returning from his Guggenheim studies under Brancusi to New York in April of 1929, with the

New York Times publishing a photograph of one of his Paris pieces in an article submitted from Paris by Ruth Green Harris, along with a quite favorable review. Two weeks later, his two-man show with Arthur Dove at Schoen's Galleries at 115 E. 60th St. opened with similar raves:

"One of the pieces (we published a photograph of it with Miss Harris's article), resembles the rudder of a ship. But it could not be mistaken for a rudder, not even by a customs officer, for Mr. Noguchi has sublimated it, with just a deft stroke, and in his skilled hands it becomes a work of art. ... But Isamu Noguchi, who is a very modest man, guiltless of pomp and arrogance, has produced sincere and often eloquent expressions in metal, which are legitimate, and never cheaply clever, sparks from the contemporary wheel. There are also some excellent drawings." ("Two Cryptic Artists," New York Times, April 14, 1929, p. 133. While in Paris Noguchi met Ione Robinson and Marion Greenwood and became lifelong friends. For more on this see my "Richard Neutra and the California Art Club" (RNCAC)).

In early May, the prize winners for the 1929 Prix de Rome also included Isamu Noguchi, with his sculpture winning an honorable mention award, being announced in the New York Times, rounding out a very successful spring of publicity for the young sculptor. ("Prix de Rome Won by Student Painter," New York Times, May 7, 1929, p. 3).

Buckminster Fuller 4D House lecture announcement, Chicago City Club Bulletin, May 27, 1929, p. 113.

Chicago architect Howard Fisher killed two birds with one stone by joining the prestigious Chicago City Club, sponsored by his brother, Arthur Fisher, and noted architect Irving Pond. He, at the same time, also arranged a City Club Forum Luncheon lecture by Buckminster Fuller on his 4D House, which he most likely had recently seen at Marshall Field's. ("Nineteen More Members Join, Chicago City Club Bulletin, May 27, 1929, p. 114. "Inventor to Tell of the 4D House," by Howard Fisher, Ibid., p. 114).

Left: "Fuller Tells of His Amazing 4D Five Room House," by Howard T. Fisher, The City Club Bulletin, June 3, 1929, p. 120. Right: Chicago City Club, 81 E. Van Buren St.., Chicago, Granger and Bollenbacher, Architects, 1929. Wikipedia.

Howard's older brother, City Club of Chicago President Walter T. Fisher, sponsored Fuller's City Club Forum luncheon lecture on his newly coined Dymaxion House. Walter had 1926 commissioned his own house in Winnetka by his brother Howard, who designed the project as his senior thesis at Harvard University. Howard Fisher, later in the early 1930's designed a penthouse apartment for his other brother Tom and his wife, dancer Ruth Page, who had a year-long affair with artist Isamu Noguchi after meeting him at his exhibition at the Chicago Arts Club in 1932, as discussed in more detail below. (Nevala-Lee, p. 116,

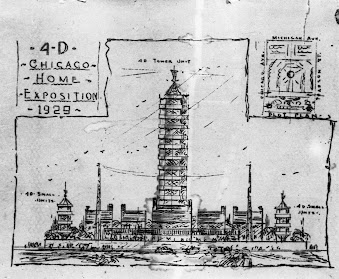

Left: "House for Mr. and Mrs. Walter T. Fisher, Winnetka, Illinois, Howard T. Fisher, Architect, Architectural Record, November 1929, pp. 461-464. Right: Sketch of 4D tower installation proposal for the 1929 Chicago Own Your Own Home Exposition, ca. May 1929, from Buckminster Fuller: Designing for Mobility by Michael John Gorman, Skira Editore, Milan, 2005, p. 35.

Fuller next displayed the Dymaxion House model on May 25th at the Chicago Homeowners Exposition at the

Chicago Coliseum, followed by the 42nd Annual Chicago Architects Exhibition at the

Arts Club of Chicago through June 13th, through the sponsorship of

Rue Winterbotham Carpenter, one of the Arts Club founders and its president until she died in 1931.

(Nevala-Lee, p. 117).

After his side trip back to Chicago, Fuller was back in Cambridge in June for the Harvard Artists and Architects Exhibit. ("Public Presentations of Fuller and Dymaxion Titles," p. 1).

Left: Byline for "The Dymaxion House," by Buckminster Fuller, Architecture, June 1929. Right: "A House for Mass Production by Buckminster Fuller," Architectural Forum, July 1929, pp. 103-104.

In an attempt to gain ever more publicity for his Dymaxion House Fuller submitted a 2,000 word piece to Architecture magazine at the same time he was exhibiting the house at the 1929 A.I.A. convention in Washington, D.C. Editor Henry Saylor published the article in the June 1929 issue and referenced Fuller in the next two issues in his "The Editor's Diary" column. In July, under his "Friday, April 26" entry, he wrote,

"Back again in New York where the convention delegates are come to see the Architectural and Allied Arts Exhibition and to gather at the banquet which closes the Sixty-second Convention of the A.I.A.. Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion House model continues to draw the interest of forward-looking architects at the Architectural League library, just as it did in an upper private room at the hotel in Washington during the convention. It stimulates the brain as setting-up exercises and a cold shower stimulate the body." ("The Editor's Diary," Architecture, July 1929, p. 46).

July also found Fuller's 600-word article, "A House for Mass Production," published by Kenneth Stowell in Architectural Forum. (See above right.). Henry Saylor's 50-word August 1929 diary entry described a recent lunch he enjoyed with Fuller at which one of their topics was regarding his interest in a potential book on Fuller to be written by Lewis Mumford for Scribner, for which Fuller had recorded a lecture for the Architectural League of New York on July 9th. After an introduction at the League meeting by Harvey Corbett, whom Fuller had recently met at the A.I.A. convention in Washington, D.C. and who confirmed that he wanted a Dymaxion House exhibit at the upcoming Chicago World's Fair, Fuller made a presentation of his house to a League audience that likely included, besides Mumford, Raymond Hood, Joseph Urban and Ely Jacques Kahn. (Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi, Best of Friends, Shoji Sadao, Noguchi Museum and Garden Foundation, New York, 2011, p. 52 and Nevala-Lee, p. 117).

Left: Isamu Noguchi and Grace Greenwood at the 1929 Harvester Maverick Festival at Woodstock, New York, August 1929. Right: Grace Greenwood (circled) and sister Marion and Noguchi on the right. From Maverick Festival Personalities.

Noguchi and painter Marion Greenwood reconnected in New York after his return and spent some time in August at the Maverick Festival in Woodstock with her and her sister Grace. The New York Times published an illustrated three-page spread in its Sunday Magazine in late August. ("An Eden of Artists Fights a Serpent," New York Times Magazine, pp. 6-7, 23).

Fuller moved to Greenwich Village for six months in mid-1929, into the studio of a sculptor.

Antonio Salemme, a friend of his architect father-in-law James Monroe Hewlett. From there, he rediscovered Romany Marie's - the perfect venue for cultivating the connections that he needed.

The tavern had recently moved to 15 Minetta St., and Fuller offered to redecorate it. Around the same time, Marie introduced Fuller to Isamu Noguchi, who had himself recently arrived from Paris with a recommendation from his mentor Brancusi to make his own discovery of Romany Marie's.

(Nevala-Lee, p. 118).

Portrait bust of Julian Levy by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from Isamu Noguchi Archive.

The art dealer Julien Levy met Noguchi in Paris in 1927, and was sculpted by Noguchi after he arrived in New York in 1929. Levy observed of Noguchi,

"Noguchi was discovering a means of applying the formal elements of sculpture to enhance the psychological implications of a portrait. Everything from the general outline to the most minute details of texture, was significant of his estimate of his subject. The choice of material, determination of scale, even the shape of the base, all were part of the general consideration, so that, if the portrait were featureless, there would still remain a sort of impression of the subject." (Herrera, p. 104).

Romany Marie fondly reminisced about Bucky's salad days in Greenwich Village.

"His family had thrown him out because they thought he was meshugah. His wife Anne, was a daughter of a great architect of the old school, Hewlett. So I carried through with Bucky. One friend [Salemme] gave him a room in the village and I gave him food, and Fuller and I began to sit up all night, discussing philosophy of the future and of living. And he was working on this house model. I could see the truth of his philosophy, and it is what Bucky proceeded to apply to his Dymaxion House, the first model of which he exhibited in my place there on Minetta Street." (Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village by Robert Schulman, Butler Books, Louisville, KY, 2006, p. 107).

Left: Romany Marie ca. 1929-30. Photographer unknown. Right: Proposed Dymaxion Hanging Restaurant for Romany Marie, 1929 by Buckminster Fuller. From Isamu Noguchi Archive.

The theme of Fuller's redesign for Marie's cafe was aluminum. Marie recalled Fuller saying,

"I'm going to fix this place up in a Dymaxion way. I'm going to throw out all the old things, and will create something new that will have essential character and lift up your spirit. He was experimenting but it wouldn't cost much, he said. The fact is, it cost plenty. I had to pay about six dollars a quart for that aluminum paint he planned to put on the walls. Well, so what, I thought. Bucky is creating for me." (Ibid., p. 105).

It was then that Marie introduced Fuller to Isamu Noguchi, who had been sent by Brancusi, who had told him, "Do like I and Matisse did, go first to Romany Marie's." Fuller and Noguchi painted everything but the kitchen in aluminum, all the walls and exposed ceiling pipes, and the lights were described by Marie as "horns of aluminum." He designed "aeroplane" chairs and tables that wiggled when you put food on them." Marie continued with a description of opening night.,

"It was the most ridiculous spectacle you ever saw in your life. It wasn't enough there was a deviation with all the luminosity - when they sat down, they all fell down. We had to bring out chairs - real chairs - and do what we could that night. And next morning I had to have a carpenter make me benches like I had before." (Ibid., pp. 106, 109).

Proposed Design for Interior of Romany Marie Tavern by Buckminster Fuller, 1929 from Buckminster Fuller: Staring With the Universe edited by K. Michael Hays and Dana Miller, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2009, p. 89.

"Night after night there developed a kinship that you could see influenced the work of the other. It seemed like every time I looked up there was these two little men talking, talking. And no question in my mind, it was what Noguchi took from Bucky that led him into his period of striking portrait busts in various new metals." (Ibid., p. 110).

Architect Hugh Ferris purportedly told Marie, "Marie, if you will give a hand to Bucky Fuller, you will go down in history." And this I believed, but of course, the reason I helped Bucky was because I believed in his philosophy, regardless of the chairs falling down and the luminosity. Bucky's experiment was a failure, but Marie promised Fuller one free meal a day for the rest of his life. (Ibid., p. 106).

Left: Bust of Lajos Tihanyi, 1929, by Isamu Noguchi from Noguchi Archive. Right: Bust of Buckminster Fuller, 1929 by Isamu Noguchi from Noguchi Archive.

On October 27th of 1929, two days before the stock market crash that heralded the Great Depression, Romany Marie staged an exhibition of paintings by Lajos Tihanyi, a painter Noguchi knew from Paris, sculpture by Isamu Noguchi, including busts of Tihanyi and Fuller, and Fuller's model of his "Dymaxion House", which ran until November 4th. ("Art News in Brief," New York Times, October 27, 1929, p. X12).

"The portrait of R. Buckminster Fuller, a likeness of the inventor, theorist and architect who became a life-long friend, is covered in extremely reflective industrial chrome. These high-tech materials created "form without shadow," Noguchi stated, meaning that the reflection itself became a sculptural element."

(From Art Story).

"Plans to Move Homes by Airship," John E. Lodge, Popular Science Monthly, September 1929, p. 47.

Fuller's 4D fantasies kept gaining traction throughout the year, with another full-page spread making the pages of Popular Science Monthly in September of 1929. Fuller predicted in the piece that within fifty years that dirigibles moving Dymaxion Houses and 4D Towers from place to place would be a "commonplace occurrence." The same month Fuller had an exhibit, perhaps a two-man show with his sculptor landlord, and presented two lectures in the studio of Antonio Salemme, where he was then still residing in Greenwich Village at 2 West 13th St., New York City.

Buckminster Fuller presenting the first model of the Dymaxion House in Fox Movietone Newsreel outtake, October 10, 1929.

The next month, Fuller made a short trip to Princeton University, where he had a one-man exhibit of his model and a lecture on October 18th, which was reported upon in a lengthy article in the Daily Princetonian. The previous week, Fox Movietone filmed a newsreel of the Dymaxion model and Fuller talking. (See above.). ("Dymaxion House of Fuller Forerunner of Economic Revolution in House Building," Daily Princetonian, October 23, 1929, p. 5).

Howard Fisher led off the November 1929 issue of Architectural Record with a six-page piece, "New Elements of House Design," in which he expounded on which direction he saw various elements of the residential house evolving in the future. He sounded like he had just attended a Buckminster Fuller lecture on the Dymaxion House; in fact, he touted Buckminster Fuller's new bathroom ideas, of which he wrote:

"The most interesting prophecy for the bathroom of the future is that of Buckminster Fuller. His design calls for the entire room to be formed in one piece with all the fixtures to be made integral. This would be delivered by truck to the job completely piped and ready to install." ("New Elements of House Design," Architectural Record, November 1929, pp. 397-403. Author's note: This quote presaged Fuller's work at the Pierce Foundation in 1931 developing his Dymaxion Bathroom concept as discussed later below. Fisher's article pleased editor Kocher so much that he commissioned him to prepare the entire 1930 Country House issue in November 1930 and invited him to be a contributing editor, a position he retained on the magazine masthead until 1937.).

Poster for "An Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by the School of New York," October 17 to November 1, 1929, The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, 1400 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge.

Perhaps through his association with Fuller, work by Noguchi was selected for display in an October exhibition at the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art in the Coop Building. Inspired by the success of the young Harvard students Lincoln Kirsten, Edward Warburg, and John Walker with the Harvard Society, at almost the same time, Abby Rockefeller and friends formed the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. At the recommendation of Harvard's Paul Sachs, Alfred Barr was selected by MOMA's trustees as the new museum's founding director.

"It is difficult to assess the precise role that the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art played in the early development of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But in April of 1930 the Modern's trustees did invite the three undergraduates, along with Philip Johnson, onto its newly formed Advisory Committee. This new committee, consisting of "young people interested in the Museum," was intended to propose ideas to the trustees. ... Agendas for the trustees' meetings were sent to each member of the Advisory Committee." (Weber, pp. 107-8).

In addition to Kirsten, Warburg, Walker, and Johnson, the Committee consisted of the Harvard Society's trustee (and later Richard Neutra client) John Nicholas Brown, Nelson Rockefeller, George Howe, and many notable others. The local press made much of the connection between the Harvard Society Executive Committee and MOMA's Junior Advisory Committee. The early history of the museum was summed up in the New York Evening Post thusly,

"The almost instantaneous success for the Society for Contemporary Art was followed before many months by the founding of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, more pretentious and with more substantial backing than the Harvard Society, but identical with its Cambridge predecessor in its basic aims. The undergraduate directors of the Harvard organization were elected to the directorate of the New York museum - acknowledgement of how much the latter owed to the germ of that idea born at Harvard." (Weber, p. 108).

Left: Ruth Parks' bronze portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from the Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: "On View at New York Galleries," Parnassus, no date, ca. December 1929. From Isamu Noguchi Archive.

Noguchi was next on display at the inaugural exhibition for the Whitney Museum of American Art, which opened on November 18, 1929. His bronze portrait bust of waitress Ruth Parks was also published in a February 1930 review of the exhibition in Parnassus. Noguchi had a penchant for sculpting people who caught his attention, such as Parks, whose 1929 bust with her hair tied on top of her perfectly oval head has all the elegance of his recent mentor Brancusi. (Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi by Hayden Herrera, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2015, p. 100).

"Housekeeping in the Air," by Amy MacMaster, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 8, 1929, pp. G1-G2.

Fuller scored a big coup in December, landing a lengthy two-page spread opening the

Brooklyn Daily Eagle Sunday Magazine. The author Amy MacMaster opened the article with almost a full-page illustration by

Harve Stein fantasizing Dymaxion living with the fashionably-dressed female owner standing next to a coffee table adorned with a Noguchi-like sculpture pressing an elevator button above the caption, "The doors of the house roll upward by the pressing of a button." MacMaster clearly spent much time with Fuller while researching the article, evidenced by her following comment.

"Buckminster Fuller is amazingly painstaking and clear in explaining his invention. He is a serious and yet high-spirited man with bright eyes and an extremely high forehead. He has a great love of beautiful things, a nimble wit and the absorption of the inventor. There are three things about Mr. Fuller's life that have had the most influence on him and may be considered the basis of his invention. First, he learned to sail boats when he was little more than a baby; secondly, he is the grandnephew of

Margaret Fuller, a women noted as a rebel against traditional conventions; and thirdly, he married the daughter of a famous architect,

James Monroe Hewlett."

(Ibid., p. G-2).

Fuller had yet another "Invitation Exhibit" in the Studio of Isamu Noguchi after moving in with him. Noguchi had just moved from his old studio in the Carnegie Building to a top-floor space on Madison Ave. and 28th Street. It had formerly been a laundry and sported high windows all the way around. "By then, under Bucky's sway, I painted the whole place silver, top, bottom, and sides, to the effect that one was almost blinded by the lack of shadows. There I made his portrait head in chrome-plated bronze, also form without shadow." (Herrera, p. 105).

"A Japanese American Sculptor Comes to New York: Isamu Noguchi," New York Times, Midweek Pictorial 30, no. 18 (December 21, 1929), p. 18.

Also in December of 1929, novelist John Erskine sat for a portrait bust by Noguchi, which was scheduled to be on display at a showing of the artist's work at the Marie Sterner Gallery in the following February. (See above and below.)

Exhibition photograph: "Fifteen Heads by Isamu Noguchi," Marie Sterner Gallery, New York (February 1 - February 14, 1930) - Photograph: Peter A. Juley & Son. From Isamu Noguchi Archive. (See also "Work by Six Japanese Artists," by Edward Allen Jewell, New York Times, February 9, 1930, p. X13). Evidenced by his early February 1930 show at Marie Sterner's Gallery, Noguchi was busy throughout 1929 making busts of people that would potentially help further the careers of his close pal and roommate, Bucky Fuller, and himself.

Left and right: Martha Graham portrait busts by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from Isamu Noguchi Archive.

During this period, Noguchi met dancer Martha Graham. His mother lived near Martha and helped with costumes for her dance company, and his sister Ailes came to study at her studio and joined her dance company. Noguchi remembered,

"I made a head of the great dancer Martha Graham soon after I got back to America. At the time she was not well known, but she lived around the corner from Carnegie Hall, nearby where I had a studio, so I used to go and watch her classes. There were many pretty girls there, and I would draw them."

Graham did not like the original bust. Noguchi remembered, "The first one was rather tragic. And Martha didn't like it; she didn't want to be tragic. She wanted to be forward-looking and full of expectations, hope. So I did another head representing the other Martha." (Herrera, pp. 107-8).

Left: Harvey Wiley Corbett portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from Isamu Noguchi Archive. F. S. Lincoln photograph. Right: "A Vision of Midtown New York," by Harvey Wiley Corbett, New York Times, October 6, 1929, 5-1.

Harvey Wiley Corbett, Fuller, and Noguchi were obviously socializing during the period Fuller was working on his Dymaxion drawings in Corbett's architectural offices evidenced by the portrait bust Noguchi created of Corbett around the time his Roerich Building was nearing completion, as will be discussed below. (See above right.).

New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell gave Isamu Noguchi's Marie Sterner show a rave review in early February 1930.

"Isamu Noguchi was introduced to the New York public last season, when he had a small show of abstract sculptural forms at Eugene Schoen's. It was a surpassingly good show, so that young Mr. Noguchi's introduction was auspicious. But it did not adumbrate the success with portrait heads that the present affair at Mrs. Sterner's gallery establishes beyond doubt. ... Among the best of the portraits are those of Harvey Corbett, Bernice Abbot, Charles Allen with the deep-set eyes, George Gershwin, Edla Frankau, whose monocle has been astonishingly conceived, and Buckminster Fuller the architect. Mr. Fuller has just invented a miraculous sort of house that maintains itself around a center of gravity, and miraculous he looks, too, in this bust of chromium plate, smoothed and highly polished. ... Isamu Noguchi is decidedly a man with a future, unless the present have anything to do with the case." ("Work by Six Japanese Artists," by Edward Alden Jewell, New York Times, February 9, 1930, p. X13).

Left: Berenice Abbott portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi from Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: George Gershwin portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from Isamu Noguchi Archive.

Left: "Ethel Waters" portrait bust by Antonio Salemme. Photo by Carl Van Vechten, 1932, courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book Library. Right: Lajos Tihanyi portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi from Isamu Noguchi Archive.

In early January, Ruth Green Harris wrote in her New

York Times column of the "Portrait Sculpture" exhibition at the

Feragil Gallery of busts by Noguchi and Fuller's recent landlord, Antonio

Salemme.

"...Antonio Salemme's "Ethel Waters"

reminds one of the head of an Egyptian Princess. The surface is as smooth as

skin. Isamu Noguchi's "Tihanyi" looks as if the metal had been

mined in this portrait shape. It speaks for Noguchi's great interest in metals.

One can hardly imagine this head drawn any other way." ("A

Round of Galleries," by Ruth Green Harris, New York Times, January

12, 1930, p. 120).

"Mass-Production and the Modern House" by Lewis Mumford, Architectural Record, January 1930, pp. 12-20.

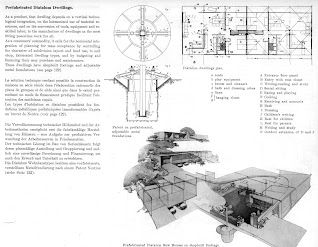

Lawrence Kocher was fascinated by prefabrication and Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion concepts and agreed to publish a two-part series in the January and February 1930 issues by Lewis Mumford, which included a critique of Fuller's Dymaxion House design. The first part of the article in January included the quote.

"Novelties in plan or design, such as those suggested in the Dymaxion House, should not obscure the fact that the great change in the shell is only a little change in the building as a whole. For lack of proper cost accounting our experimental architects have been butting their heads against this solid wall for years; but there is no reason that they should continue. ... In short: the manufacture house cannot escape its proper site costs and its communal responsibilities."(See above and also earlier above). (Ibid., p.18)

Mumford included a footnote under Fuller's model which read, "Walls (no windows) of transparent casein; inflated duralumin floors, heat, light, refrigeration supplied to it individually, through central mast, by Diesel engine, water from well."

In Kocher's February issue, Mumford continued almost as if he were in conversation with Fuller:

"Since the parts of a building have been industrialized, it has naturally occurred to certain intelligent designers that the whole might be treated in the same manner, hence various schemes for single family unit-houses, designed for greater mechanical efficiency. Those who approach the problem of the modern house from this angle suggest that the mass house may eventually be manufactured as cheaply and distributed as widely as the cheap motor car. ... the mere ability to purchase such houses easily and to plant them anywhere would only add to the communal chaos that now threatens every semi-urban community. *Mr. Buckminster Fuller already perceives this danger. "The Dymaxion Houses," he writes me, "cannot be thrown upon the world without a most adequate 'town plan,' really a universal community plan." ("Mass-Production and the Modern House (Part Two)," Lewis Mumford, Architectural Record, February 1930, p. 110).

Dymaxion House Exhibit-Lecture Announcement, Architectural League of New York, 115 E. 40th St., New York, February 4-11, 1930.

Still having high hopes of exhibiting his Dymaxion House at "The Century of Progress" fair in Chicago, Fuller seemingly collaborated with Harvey Wiley Corbett to have the New York Architectural League host an exhibition of his new and improved house model from February 4th to the 11th, 1930. Fuller presented a lecture to the League on Friday, the 7th at 8:00 p.m. on the "Philosophy-Economics, Dynamics, and Mechanics of Dymaxion Design." (see above).

Left: "4D - Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion House, March 12-14, 1930, Old Fogg Museum, Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. Right: Bronzes by Isamu Noguchi, February 27th through March 15th, 1930, Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, 1400 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge.

Fuller soon convinced Lincoln Kirsten to bring him back in

1930 to exhibit his improved model of the Dymaxion House in the courtyard of

Harvard's Fogg Museum while also exhibiting his friend Noguchi's sculptures and

drawings in the Society's Coop Building rooms on Massachusetts Avenue. Noguchi

also returned with all the busts he had completed the previous year, including

Fuller, Marion Greenwood, Martha Graham, George Gershwin, Harvey Wiley Corbett,

Berenice Abbott, Nicholas Roerich, and others. Noguchi perhaps took the

opportunity to also capture the bust of Lincoln Kirsten. (See below left.).

Fuller's 4D-Dymaxion exhibition was shown immediately after the Harvard show at the Wadsworth Atheneum by A. Everett "

Chick" Austin.

(Gaddis, Eugene R.: 'Magician of the Modern. Chick Austin and the Transformation of the Arts in America, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2000, p. 140)

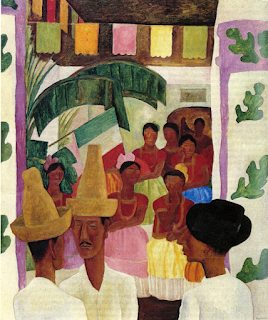

Following up on the Mexican West Coast invasion of 1930, the Harvard Society of Contemporary Art scheduled the exhibition "Modern Mexican Art" for March 21st through April 12th, hard on the heels of Noguchi and Fuller. Lithographs were solicited from Diego Rivera, then still in San Francisco, and an assemblage from several New York galleries of work by José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jean Charlo, which were also included. (Weber, pp. 104-5. See also my "Richard Neutra and the California Art Club" for much more.

Left: Lincoln Kirsten portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929, from Isamu Noguchi archive. Right: "Sculpture by Noguchi," Arts Club of

Chicago, March 26-April 9, 1930. Portrait bust of Marion Greenwood on the

cover. From Isamu Noguchi Archive.

Fuller and Noguchi packed their materials from the Harvard

show into Fuller's Nash station wagon and left Harvard for Chicago, where they

both also exhibited. Noguchi's sculpture exhibition ran first at The Arts

Club of Chicago from March 26th through April 9th, concurrently with

"Paintings by Pablo Picasso." His bust of Marion Greenwood was chosen

for the cover of his exhibition catalogue. Fuller's show "Exhibition

of Models and Drawings of Dymaxion Architecture by Buckminster Fuller,"

ran from May 8th through the 13th alongside "Paintings by George

Rouault." (Listening to Stone, the Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi by

Hayden Herrera, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 2015, pp. 108. See

also Arts

Club of Chicago. below).

Left: "An Exhibition of Work of 46 Painters & Sculptors Under 35 Years of Age," April 12th to April 26th, 1930, Museum of Modern Art, 730 Fifth Avenue, New York. Right: Therese Thorne portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929-30,

Isamu Noguchi Archive.

After his Chicago Arts Club exhibition was under way Noguchi

left for New York to make sure that his section of the MOMA group

show, "An Exhibition of Work of 46 Painters & Sculptors Under 35

Years of Age," was well displayed before continuing on to

Paris. Between April 12th to April 26th, Noguchi's sculpture was on display

"An Exhibit of Work of 46 artists under 35 Years of Age" at the fifth

ever exhibition of the new Museum of Modern Art in the Heckscher

Building.

Noguchi had four works in the show, including a portrait bust

of his current paramour, young New York socialite Therese Thorne, which had

also previously appeared in the "Fifteen Heads" show at the Marie

Sterner Gallery. Fuller wrote from Chicago to Noguchi on April 4th, asking

him to meet with Harvey Corbett once again before he sailed for Europe to

reinforce his feelings about the Dymaxion House and his plans to accept it for

display at the Chicago 1933 World's Fair. (Fuller to Noguchi, April 4,

1930, Noguchi

Archive).

Left: Telegram from Buckminster Fuller to Isamu Noguchi on the steamship Aquitania, April 15, 1930. From Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: Portrait bust of Isamu Noguchi by Arno Breker, 1930. Courtesy Isamu Noguchi Archive.

Just as Noguchi was embarking for Europe, Fuller sent him a bon voyage telegram in his own inimitable style, which clearly demonstrated the bond that had formed between the two personas. Noguchi found time to sit for his portrait with his 1927 European sculptor neighbor, Arno Breker, while back in Paris. (See above for example.).

As Noguchi sailed for Europe, Fuller lectured on the Dymaxion House twice more in Chicago before conducting an Eastern swing and returning to Chicago for his own Arts Club exhibition. Likely through Howard Fisher, who had designed a house for his brother in Winnetka, he gave a public lecture and had a one-man show at Winnetka High School on April 15th. Similarly, on the 19th, he gave another lecture and one-man show at the

Chicago Fortnightly, a women's club that included notable early members Jane Addams and Harriet Monroe.

.

The next week found Fuller at Carnegie Institute of Technology on April 24th for a general university three-hour lecture in the Little Theater and a one-man show in the Fine Arts Department.

(See above.). Fuller next traveled on to The Newark Museum for yet another one-man show and lecture on May 1st, sponsored by

Holger Cahill.

(See below.)

Newark Museum of Art, ca. 1930s.

Fuller's next appearance was at the prestigious Yale University Architectural School on May 3rd in a lecture arranged by his 4D House design-mate Paul Schwiekher, who was then attending, Julian Whittlesey, and others. Student George Nelson was also in attendance, along with Ricky Harrison, who assembled the Dymaxion model without instructions. Having already seen Fuller's presentation at the previous A.I.A. convention, Dean Meeks refused to attend. Fuller finally returned to Chicago for his exhibition at the Arts Club sponsored by club president Rue Winterbotham Carpenter. He followed his May 8th to May 13th run with an appearance at the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club on 15th and the Chicago University Renaissance Club on the 18th.

"Demonstration Health House for Dr. Philip Lovell, Los Angeles, Richard J. Neutra, Architect, Architectural Record, May 1930, pp. 433-439.

Fuller next spent the first week of June at the annual A.I.A. convention in Washington, D.C., which included a symposium on Modern Architecture. In a summary of the happenings at the convention, it was reported that,

"Mr. George Howe of Philadelphia fired a salvo to celebrate the victory of the Modernists which he seemed to consider a fait accompli. If he was tempted to speak too lightly, too jestingly, too disrespectfully of the dead, he may be forgiven for an over-confidence bred of zeal. ... From the martial tone of Mr. Howe's remarks one conjured up a bloody picture of Architects in tin hats 'neath the rockets red glare, and bombs bursting in air, shouting the battle cry of freedom; and mopping up their adversaries, so to speak." ("Conventional Behavior," by An Eyewitness, The Octagon, June 1930, p. 4).

The Dymaxion House was on display in the convention's Mayflower Hotel Main Ballroom. Fuller was nonplussed by a mass walkout of his lecture by "Easterners" led by William Delano. Fuller was likely inspired by Howe's talk and perhaps made his initial connection, which soon led to his taking over control of Philadelphia's T-Square Journal (Shelter) in early 1932. Fuller's Dymaxion House model finally came to rest for the rest of the summer of 1930 in the showroom of designer Donald Deskey. ("Public Presentations of Fuller and Dymaxion Items," p. 2).

"Dymaxion House designed by R. Buckminster Fuller" in "The Week-End House" by Knud Lonberg-Holm, Architectural Record, August 1930, p. 180.

Fuller was able to attract the attention of Architectural Record assistant editor and technical writer Knud Lonberg-Holm for inclusion of Dymaxion in Holm's piece on "The Week-End House." (See above. Author's note: Lonberg-Holm's fellow assistant editors under A. Lawrence Kocher was Robert L. Davison, for whom Fuller would in 1931 work at the Pierce Foundation in Buffalo on the development of a prefabricated bathroom, and Ted Larson, whom, along with Holm, Kocher, and Frey, would soon become members of Fuller's Structural Study Associates. (Nevala-Lee, p. 129).

Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros were well represented in a huge exhibition of "Mexican Arts" at the Museum of Modern Art from mid-October through early November of 1930. The show, conceived by Ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow, travelled around the country for the next two years. ("Mexican Art Shown in Exhibition Here," New York Times, October 14, 1930, p. 24).

"The Nation's Honor Roll for 1930," The Nation, January 7, 1931, cover and p. 8.

In the January 7, 1931, issue of The Nation, Buckminster Fuller was listed along with architects Henry Wright and Eero Saarinen for being on "The Nation's Honor Roll for 1930." Fuller's citation read: "Buckminster Fuller, engineer, of New York, for his

pioneering work in developing the potentialities of mass production, new

materials and new engineering principles for housing that is practical, cheap

and of good design."

Around the same time, Richard Neutra arrived in New York from Europe on the way home to Los Angeles from his career-making around-the-world lecture trip in 1930. Upon his arrival, Neutra doggedly made the rounds of architects, designers, and editors in his quest to make a name for himself. He met architects Raymond Hood, Ely Jacques Kahn, Joseph Urban, and Ralph Walker,

editors Henry Saylor of Architecture and A. Lawrence Kocher of Architectural

Record, and the artists and designers Bruno Paul, Rockwell Kent, Paul

Poiret, Lucian Bernhard, and Buckminster Fuller.

While Neutra was in New York in late 1930 and early 1931, he lectured on "The New Architecture" January 4th at the Art Center under the auspices of the Art Center, Contempora and AUDAC and on January 7th, "New Architecture Shapes a New Human Environment in Europe, Asia, and America," at the Roerich Museum (see below) with Kocher, Frey, Lescaze, Fuller, Noguchi and Harvey Wiley Corbett, the building's architect, perhaps in attendance. Fuller himself had lectured at the Roerich Museum during the fall of 1930. ("R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight," and "What is Going On This Week," New York Times, January 4, 1931).

"Architecture of the Master Building," Roerich Museum, Harvey Wiley Corbett, Architect, Archer, No. 3-4, 1929, pp. 24-25. From Roerich Museum Archive.

Left: Roerich Museum and Manor Apartment Building, New York City, Corbett, Harrison, and MacMurray, Sugarman and Berger, Associated Architects, Architectural Record, December 1929. Right: Roerich Museum Bulletin, January 1931, front cover and p. 12 announcing the January 7th Neutra lecture.

The previous January, between the 8th and 31st, architectural designs by Harvey Wiley Corbett were on display in the same Roerich Museum in the building he designed and completed on October 17, 1929.

Fuller enjoyed his own one-man show and lecture at the Roerich Museum in the fall of 1930. (Roerich Museum: A Decade of Activity, 1921-1931, Roerich Museum Press, 1931, pp. 14, 63).

Fuller also had fall shows at the Dalton School, where he had two exhibits and lectures to both the senior class and the general school. That was followed by another in the apartment of

Mrs. Murray Crane, one of the Museum of Modern Art's founding committee members and patron of the Dalton School. Additional fall of 1931 shows were held at the Downtown Galleries and the Columbia School of Architecture.

("Public Presentations of Fuller and Dymaxion Items," p. 2)

Left: Nicholas Roerich portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1929. Right: Nicholas Roerich posing for Isamu Noguchi, 1929. Both from the Isamu Noguchi Archive.

Neutra confirmed the luncheon in a letter to his wife Dione in Zurich.

"Today I was the guest of honor of four of the most influential architects of New York who, together, have a combined building budget of between forty and fifty million dollars: Raymond Hood, Ralph Walker (New York Telephone Building), Ely Kahn (the prolific), and Joe Urban who is the architect for the New School for Social Research where yesterday I gave the opening speech in the new auditorium, to be followed by another one tonight and Friday. My fee is $150 which is a godsend. My financial calculations regarding my stay in New York were somewhat naive; one has to have a front. These four architects dominate the Chicago World's Fair. They prefer to honor me at a luncheon than let me participate in the fair." (Richard Neutra to Dione Neutra December 1930, from Promise and Fulfillment, p. 200. Author's note: The Chicago World's Fair was covered in great detail in the July 1933 issue of Architectural Forum. See discussion later herein.).

Neutra was concerned enough with comments at the luncheon from Kahn regarding his Bonwit Teller project, which Schindler had consulted on the previous summer, to mention them to Schindler during a January 14th Architectural League exhibition planning letter.

"By the way I do not know on what terms you stand with Kahn. I thought he was in competition with you in this Teller business. ... Do you believe he would particularly oppose anything you support? (Richard Neutra to R. M. Schindler, January 14, 1931, Schindler Collection, UC-Santa Barbara).

Having arrived in New York in December of 1930, Neutra met with Architecture editor Henry Saylor. He just "dropped in" on his way around the globe. Neutra related to Saylor, the Japanese architects' insatiable love of books and periodicals on the subject. "The Japanese are hungry for information, and take all the architectural periodicals they can find. Even though the text is unintelligible to most of them, the pictures mean a lot." In the same article Saylor mentioned Buckminster Fuller's making of The Nation's "Honor Roll," "...for his pioneering work in developing the potentialities of mass production, new materials, and new engineering principles for housing that is practical, cheap, and of good design" ("The Editor's Diary," by Henry Saylor, Architecture, February 1931, p. 108).

In January Neutra lectured on "The New Architecture" on the 4th at the Art Center under the auspices of the Art Center, Contempora and AUDAC and on the 7th at the Roerich Museum (see below) on "New Architecture Shapes a New Human Environment in Europe, Asia and America" with Henry Saylor in attendance at the former lecture and Fuller, Kocher, Frey and Lescaze perhaps in attendance at one or all of the others.. ("R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight," and "What is Going On This Week," New York Times, January 4, 1931. See also "The Editor's Diary, Architecture, March 1931, p. 173.).

During this time, Neutra also made a cold call on Buckminster

Fuller after seeing his name in the Nation. Neutra thought that Fuller's Dymaxion House represented "a distinctly advanced

segregation of functions," which led them to consider a collaboration.

Fuller had just finished two presentations at banker Frank A. Vanderlip's New

York residence, the second week of January, trying to interest his financial

colleagues in some fashion. At one of the two Vanderlip dinner meetings, Fuller

did meet Clarence Woolley of the American Radiator and Standard Sanitary

Corporation, which operated the Pierce Foundation in Buffalo that was designing

a new type of bathroom. (Nevala-Lee, p. 126).

Fuller asked Neutra to accompany him to a follow-up lunch

meeting with Vanderlip, whom he met through the architectural partner of Harvey

Wiley Corbett. Since Neutra had a practical background that Fuller lacked and

he seemed to Fuller a likely candidate for Vanderlip, who owned 16,000

acres in Palos Verdes in Southern California that was ripe for major

real estate development. The meeting did not bear any fruit for Neutra, but

Fuller, who had kept in touch with Woolley about the Pierce Foundation, ended

up receiving an offer on April 11th from former Architectural Record associate

editor Robert L. Davison, whom he had also met at the A.I.A. convention, to join

the Foundation's bathroom program. It was, he thought, a wonderful chance to

develop a prototype of a "Dymaxion" bathroom. (Nevala-Lee, p. 126. See also my "Kocher,

Neutra, Frey").

Left: The New School for Social Research, New York City, Joseph Urban, Architect, Architectural Record, February 1931, pp. 138-145. Right: New School for Social Research Auditorium, Joseph Urban, Architect, bid., p. 145.

Neutra also met

Dr. Alvin Johnson, the director of the

New School for Social Research, whose new building was recently completed by Joseph Urban.

(See above.). Through Urban's help, Neutra was also chosen by Johnson to deliver the opening three lectures in the new auditorium "to test its novel acoustics, as it were." On three successive nights on January 4, 5, and 6, 1931, Neutra lectured on "The Relation of the New Architecture to the Housing Problem," "The American Contribution to the New Architecture," and "The Skyscraper and the New Problem of City Planning." Dr. Johnson would soon become a member of Buckminster Fuller's Structural Study Associates, as discussed later herein.

("New Social School Viewed by Public," New York Times, January 2, 1931, p. 27. "R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight," New York Times, January 4, 1931. Life and Shape by Richard Neutra, p. 258, and for much on his self-promotional efforts while in New York, see Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932

by Richard Neutra, p. 258, and for much on his self-promotional efforts while in New York, see Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 , pp. 193-209. See also Hines, p. 98.

, pp. 193-209. See also Hines, p. 98.

Left: Portrait Bust of Jose Clemente Orozco, 1931 by Isamu Noguchi. Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: Jose Clemente Orozco, left, and Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, right, at work on "Struggle in the Orient" at the New School for Social Research, January 1931.

An artist Neutra had befriended in Los Angeles before he left for his around-the-world tour, Jose Clemente Orozco, was decorating the walls of the New School with his murals as the building was being completed; thus, the two of them most likely reconnected as Neutra was rehearsing and lecturing throughout January.

Left: Richard Neutra, 1930. Photographer unknown. (From Riley, p. 30). Right: Lovell Health House 1930 model. Richard Neutra, Architect. From Riley, p. 49. Photographer unknown. Commissioned by the New York Museum of Science and Industry, 220 E. 42nd St., New York, Daily News. Commissioned by the New York Museum of Science and Industry, 220 E. 42nd St., New York, Daily News Building. (The model was borrowed by the Museum of Modern Art for the Modern Architecture, International Exhibition in February 1932.).

In his oral history, Neutra's then-apprentice Harwell Hamilton Harris remembered corresponding with Neutra in New York and being allocated $500 to build the model.

"And the present [for the Museum of Science and Industry] was to be represented by the Lovell House. And would I go to Conrad Buff, the painter, and get from him the working drawings of the Lovell House, which he had left with him when he went to Europe.

Five hundred dollars! That knocked me over. Why you could build a house for that, not just a model. And then, because the house was metal, I decided the model should be metal, too. So I went to Harry Schoeppe, who had taught metalwork, jewelry, and things like that at Otis, and asked him if he would help me make it out of metal. Which he agreed to do. So we made it in the garage of his house over in Altadena, and we spent at least three months on it. He did all the metalwork; I did everything else on it. Neutra returned just before we shipped it, I believe; I think he saw it before we shipped it east." (Interview of Harwell Hamilton Harris).

As Fuller with his Dymaxion House, Neutra's Lovell Demonstration Health House gained much exposure during his January lecture blitz in New York. The Director of the New York Museum of Science and Industry, C. R. Richards, commissioned Neutra for a model of his Lovell House "to complete a permanent exhibit of human habitations from cave dwellings to the present" for their new location on the fourth floor of Raymond Hood's soon-to-be completed Daily News Building. Richards chose the house "as the most convincing and rational specimen of the new architecture...because of the enthusiastic recognition it accorded it in Paris, Berlin, New York, and Tokyo." ("Architecture is Advancing in West, California House is Chosen for Museum Display," Pasadena Star News, August 31, 1931. Hines, p. 100.). Around the same time, Philip Johnson's father, Homer, and his ALCOA company and White Motor Company were collaborating on a new bus design. Homer asked Philip for a recommendation for someone outside the White Motor Company to design an aluminum bus. Philip immediately thought of Neutra. For a flabbergasted Neutra who knew nothing about bus design, the extravagant design fee of $150 per day and free room and board at Homer's private club in Cleveland was too much to turn down. (Philip Johnson to Neutra, December 30, 1930. Dione Neutra Papers. Hines, p. 121).

Bus Design for White Motor Company (unbuilt), Cleveland, Ohio, 1931, Richard Neutra, Designer. (Hines, p. 100).

During his time in Buffalo between April and July, Fuller

kept Neutra, by then back in Los Angeles, informed of his progress on the

bathroom. Neutra offered to provide a draftsman to "ripen and

harvest" it. Word reached Knud Lonberg-Holm, the technical writer and also

an associate editor for Architectural Record, who asked to see the

drawings. Davison, who spent most of his time in New York, was angered by what

he saw as a betrayal. Fuller shot back that he had the right to promote his own

concepts and quit the Pierce Foundation at the end of July 1931. (Nevala-Lee,

p. 127).

Left: Starrett-Lehigh Building, 601-625 W. 26th St., New York, Walter and Russell Cory, Architects, 1931. Photo by Berenice Abbott, 1936. From Wikipedia. Right: Buckminster Fuller on the roof of the Starrett-Lehigh Building with the Empire State Building, 1931. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Fuller Papers, Stanford University.

Upon returning to New York in late 1931 following his stint at the Pierce Foundation in Buffalo and a late summer retreat on the family's Bear Island, Fuller excitedly found and rented a vacant storeroom on the top floor of a recently-completed warehouse and freight terminal at 601 W. 26th St. known as the Starrett-Lehigh Building in the West Chelsea neighborhood. The recently completed building was still mostly unoccupied due to the depression and was soon to be included in Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock's "Modern Architecture, International Exhibition" at the new Museum of Modern Art.

(The International Style: Exhibition 15 and the Museum of Modern Art by Terence Riley, Rizzoli, New York, 1992, p. 175. See also my "Kocher, Neutra, Frey").

Letter from Buckminster Fuller to Evelyn Schwartz, November 24, 1931. From Fuller Collection, Stanford University. Also in Impossible Heights: Skyscrapers, Flight, and the Master Builder by Adnan Morshed, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2015, p. 136.

The rooftop views of New York were spectacular and covered the entire city block. Fuller's storeroom "penthouse" and rooftop served as a perfect location for wild parties, his Structural Study Associate meetings, and rendezvous for his then 18-year-old lover Evelyn Schwartz, whom he had been seeing since meeting her at Romany Marie's in 1930. Fuller had a wonderful view of the recently completed Empire State Building from this location and brought Diego Rivera here while he was engaged in his one-man show at MOMA. Fuller recalled the two of them having to climb nineteen stories after the elevators shut down at closing time and the portly Rivera having to stop to rest at every landing. (Finding My Way: The Autobiography of an Optimist by Evelyn Steffanson Nef, Francis Press, Washington, D. C., 2002, pp. 50-55. Nevala-Lee, p. 128-131).

Left: Catalogue of "Exhibition of Bronzes and Drawings by Isamu Noguchi," Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, from Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: Berenice Abbott portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi. Ibid.

From December 24, 1930 to January 25, 1931 Noguchi, who had recently returned from Europe, China and Japan, was in a two-man show with Chana Orloff at the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy where his bronze portrait busts of Martha Graham, Berenice Abbott, Marion Morehouse, Lajos Tihanyi and three others were shown along with thirty of his drawings. (See above right.).

After Neutra had returned to Los Angeles, February 24th

found Frank Lloyd Wright at the New York Woman's City Club for a lecture and

debate about architecture at the Chicago World's Fair with Buckminster Fuller,

Katherine Dreier, Lewis Mumford, and Raymond Hood in attendance. In his

autobiography Wright found Fuller to be "a dripping rag" although he

tolerated him until Fuller, likely confident that Harvey Wiley Corbett still

intended to display his Dymaxion House, described the 1933 Chicago World's Fair

"to be the last word in modern architecture." (Wright in New

York by Anthony Alofsin, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2019, pp.

211-212).

Two additional meetings, a few days later in New York, were

organized by Wright's supporters, Paul Frankl, Lee Simonson, Douglas Haskell,

Alexander Woolcott, and Lewis Mumford, to protest Wright's exclusion from the

Century of Progress exhibition. Harvey Corbett led the opposition to Wright's

involvement. (Ibid., p. 212).

Left: "The Conquest of Mexico" by Diego Rivera. Exhibited at the Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition, April 18th to 25th, 1931, Grand Central Palace, New York. From "The Architectural League and the Rejected Architects," by Douglas Haskell, Parnassus, May 1931, p. 12. Right: "Aluminaire: The House for Contemporary Life," Grand Central Palace, April 18th to 25th, 1931. From Albert Frey, Innovative Modernist, edited by Brad Dunning, Radius Books, Palm Springs Art Museum, 2024, p. 48.

A photo of Diego Rivera's mural "The Conquest of

Mexico" was included in a group of Mexican objects on display in the April

1931 Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition. Photos of Diego's work were

curated by Diego's then-agent, Frances Flynn Paine, at the Grand Central Palace

while Diego and Frida were still in San Francisco. Paine perhaps intended to

hype Rivera's upcoming one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art beginning in

December. Douglas Haskell included a photo of Rivera's "The

Conquest of Mexico" in his review of the expo in the May issue of Parnassus, which

he also spent at least half a page extolling the virtues of Kocher and Frey's

Aluminaire House. (See above left and right.)..

Left: "Mexicans in Our Midst," Survey Graphic, May 1931, front cover. Right: "The Life of the People," by Diego Rivera, Ibid., pp. 178-9. Photos of Rivera frescoes in Mexico City's Public Education Building by Tina Modotti.

Diego Rivera and Frida returned to Mexico from San Francisco for five months in 1931

before returning to New York in November for his second American one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art, which opened in December. (Author's note: Photographs of Rivera's work were included in the New York Architectural League's 50th annual anniversary exhibition in the Architecture and Allied Arts Exposition at the Grand Central Palace the previous April and some of his work also appeared in "The Arts of Mexico" exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art in November of 1930. See my "Schindler-Scheyer-Eaton-Ain" for much more on Rivera's time in San Francisco in 1930-31, and my "Packard Family Architectural Connections" for more on Rivera's time in San Francisco for the 1939-40 Golden Gate International Exposition."Collector's Room" for Ely Jacques Kahn, by Buckminster Fuller, 1931.

Shortly after Neutra met with Fuller in early 1931, New York Architectural League vice-president Ely Jacques Kahn commissioned Fuller to design what he called a "Collector's Room" for displaying sculpture intended to be on display in the Grand Central Palace for the upcoming Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition from April 18th to 25th. The room, which resembled the streamlined form of the Dymaxion car, was to have niches for displaying sculpture. It was "an outwardly tensed, ovaloid shaped, hyperbolic parabola, faceted, tension (tent) fabric room for installation in the Grand Central Palace at a proposed Architectural Show for a sculptor's exhibit room - lighting for the room and its sculptural exhibits to diffuse inwardly through the comprehensive translucent, tensed, white fabric 'walling,' from lights exterior to the structure." (Letter from John Dixon, Fuller's assistant, to Donald Robertson, dated December 6, 1954, M1090, ser. 4, box 2, folder 4, Fuller Papers, Stanford.).

Left: Contemporary American Architects by Ely Jacques Kahn, Whittlesey House/McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc., New York, 1931. Right: "Fifth Avenue Entrance Bonwit Teller, Fifth Avenue at Fifty-Sixth St., New York City, Ibid., p. 100.

Around the same time, Kahn published a book on "modern" architecture, which included many photos of his close to fifty projects, including his Squibb Building and the Bonwit Teller project (renovation of the Stewart & Company Building by Warren & Wetmore) that R. M. Schindler had worked on in 1930.

Around the same time, Kahn asked Noguchi to prepare a proposal for a monument to the Battle of Appomattox Courthouse, the final engagement of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia before General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General U. S. Grant. Noguchi produced a model with 48 stone slabs inscribed with the names of the dead from 48 states in four rows.

If the "Collector's Room" had been built, it undoubtedly would have included Noguchi's portrait busts of Harvey Wiley Corbett, Fuller and Kahn himself among many of Noguchi's other recent work and been on display along with Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey's Aluminaire House, Diego Rivera's fresco "Conquest of Mexico" and Neutra and R. M. Schindler's displays of their Southern California work mentioned earlier.

(Buckminster Fuller: Starting With the Universe, edited by K. Michael Hays and Dana Miller, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2009, p. 26). (Author's note: See much more about this exhibition in my "A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, Richard Neutra, R.M. Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright, Albert Frey and the Evolution of Modern Architecture in New York and Southern California.").

Left: Ely Jacques Kahn portrait bust by Isamu Noguchi, 1931, from Isamu Noguchi Archive. Right: Aluminaire: A House for Contemporary Life by A. Lawrence Koche and Albert Frey, Architects, The Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition, Grand Central Palace, New York, April 18-25, 1931, from Albert Frey, Inventive Modernist, edited by Brad Dunning, Radius Books and Palm Springs Art Museum, 2024, p. 4..

Left: "Squibb Building, 745 Fifth Avenue, New York City, Kahn. p. 95. Right: Third from left, Ely Jacques Kahn (Squibb Building), 1931 Beaux Arts Ball at the Hotel Astor.

The 1931 Beaux Arts Ball was held at the Hotel Astor and sported a theme, "Fete Moderne - a Fantasie in Flame and Silver." This was announced as the last ball for the venerable Hotel Astor, as the location would from then on be held at the new Waldorf Astoria. The ball's "Skyline of New York" was made up of