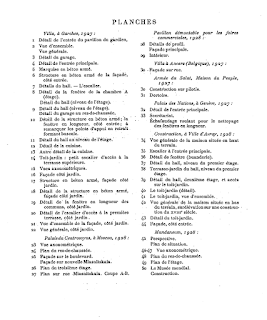

Albert Frey at the office of Eggericx and Verwilghen, 1930. Photographer unknown. From Albert Frey, Inventive Modernist, edited by Brad Dunning, Radius Books, Palm Springs Art Museum, 2024, p. 37. Art Museum.

Much has been written about Albert Frey (1903-1998) over the years, with most of the attention being placed on his seminal work establishing Palm Springs as the "Mecca of Desert Modernism." Joseph Rosa's Albert Frey, Architect, published in 1990, was a remarkable piece of work and satisfied our modernist appetites. The recent Albert Frey: Inventive Modernist book, edited by Brad Dunning and the concurrent exhibition and rededication of Frey's Aluminaire House after its relocation from the East Coast and restoration by the Palm Springs Art Museum, sparked a whole new wave of interest and piqued my fascination to learn much more about his little-known formative years in Europe. What I was able to uncover completely amazed me.

Rosa briefly summarizes Frey's childhood; therefore, I will begin with his graduation from the Institute of Technology, or informally known as the Technikum, in Winterthur, Switzerland, in 1924. Frey was trained in traditional building construction and received technical training rather than architectural design instruction in the then-popular Beaux-Arts style. Before receiving his diploma, Frey apprenticed with the architect A. J. Arter in Zurich and worked in construction during school vacations.Left: Kunstgewerbliche Arbeiten aus den Werkstätten der Gewerbeschule, Rentsch, Zurich, 1925. Right: Das Werk, Vol. 12, No. 9, September 1925, front cover.

While working for Arter, Frey began to become interested in the modern movement through exposure to architectural journals such as the Swiss Das Werk, published in Zurich, and attendance at exhibitions at the nearby Gewerbschule, a trade school established along the lines of the Bauhaus. Frey sensed that staying in Zurich was not an option since the best architectural school in Zurich was controlled by Karl Moser, and the students he produced were in high demand by local architects.

After a post-graduation sketching trip to Italy, Frey thought that he would have to emigrate to begin his career as a fledgling modernist. His first choice was France, but, at the time, it was not possible for a German-Swiss national to get a work permit there. Frey became aware of the exciting modernist developments in Belgium, so he packed his bags and left for Brussels in September 1925. (Rosa, p. 13).

Left: "Junge Kunst in Belgium, Architect Victor Bourgeoie und Gartenarchitekt L. Van der Swaelmen, Brussel/La Cite Moderne" by Hannes Meyer, Das Werk, Vol. 12, No. 9, September 1925, pp. 257-276. Right: "J.-J. Eggericx und L. Van der Swaelman, Gartenstadt-Le Logis-in Boitsfort, Brussel,", Ibid., p. 263.

After viewing Das Werk, the above 20-page article by Hannes Meyer in the special issue on the Belgian modern architecture and art scene, Frey immediately traveled to Brussels to seek employment with the young rising modernist star Victor Bourgeois. Bourgeois could not immediately put Frey to work but recommended that he try his colleagues J.-J. Eggericx and Raphael Verwilghen, who were also situated in Brussels and represented in the same article. (See above right). (Author's note: Frey may also have seen the articles in the May 1925 issue of Das Werk submitted to editor Josef Gantner by Werner Moser and Richard Neutra, who were both then at Taliesin, apprenticing under Frank Lloyd Wright. See also my "Taliesin Class of 1924" for more on this.

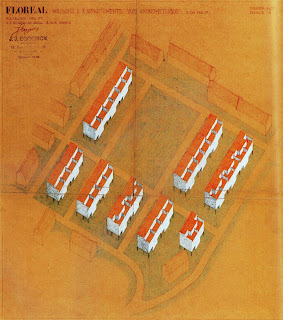

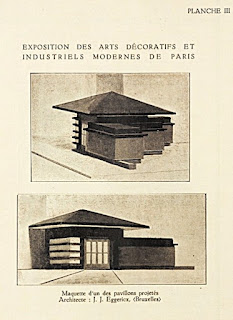

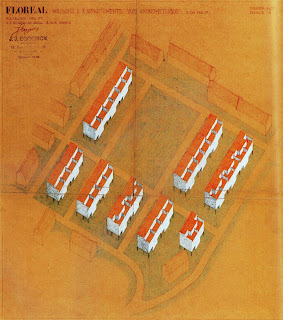

Frey's timing could not have been better, as Eggericx and Verwilghen had plenty of routine construction drawing and specification work for the fledgling architect on their garden city developments, Le Logis and Floreal. They also happened to have projects on display in Paris at the 1925 International Exposition of Modern and Industrial Arts alongside Victor Bourgeois, Louis Van der Swaelmen, and other Belgian modernists. His new employers had also been editors of a well-respected monthly journal, La Cité, for the previous six years. Victor Bourgeois's Cité Moderne was awarded the Grand Prize at the Paris Exposition, while Eggericx was awarded a medal of honor. (See above for example).

"Special Issue dedicated to the Exposition of Industrial and Modern Arts in Paris," La Cité, Vol. V, No. 7, August 1925, front cover and editorial.

Frey's timing could not have been better, as Eggericx and Verwilghen had plenty of work for the fledgling architect on their garden city developments, Le Logis and Floreal, at that time. They also happened to have projects on display in Paris at the 1925 International Exposition of Modern and Industrial Arts alongside Victor Bourgeois, Louis Van der Swaelmen, and other Belgian modernists. His new employers had also been editors of a well-respected monthly journal called La Cité for the previous six years.

At this point, I need to backtrack to the founding of La Cité to put perspective on Alert Frey's fortuitous involvement and deep embedment in the Belgian modern movement. As yet unknown to each other, Eggericx and Verwilghen were in England during World War I, separately involved in the preplanning of Belgium's reconstruction after the war, and imbued themselves in the Garden City Movement.

Left: Cambridge en Poche, Guide Pour nos amis Belges for Lilian Clarke by Jean Eggericx, Bowes & Bowes, Cambridge, 1914. Right: Garden Cities and Town Planning, Vol. V, No. 4, April 1915, front cover. (Author's note: Raphael Verwilghen published an article titled, "Un Cercle d'Etude Pour L'Examen des Problems de Reconstruction en Belgique" in the January 1916 issue.)

Eggrericx fled war-torn Belgium in 1914 and settled in the college town of Cambridge. He thoroughly studied the city and was very impressed with its architecture. He collaborated with a botany professor named Lilian Clarke to produce a small guidebook for fellow Belgians waiting out the war in Cambridge. In the book, he sketched the city's architecture and discussed the main buildings: university colleges and churches. It was, perhaps, due to the favorable review in the Cambridge Daily News that Eggericx was appointed professor of architecture at Caius College in December of 1914. (Culot, p. 57).

Left: Jean-Jules Eggericx, February 1917. Photographer unknown. From J.-J. Eggericx, Gentleman Architecte, Createur de Cites-Jardins, edited by Maurice Culot, AAM Editions, 2012, p. 54. Right: Raphael Verwilghen, 1919, Ibid., p. 62.

In February 1915, an important congress was convened in London devoted to the reconstruction of Belgium after the end of the First World War. There were over 300 Belgian participants, likely including Eggericx and Verwilghen, who had not as yet met. The proceedings of the congress were reported in detail in the April issue of Garden Cities and Town Planning. In June, Eggericx started working at the Daimler Automobile Factory in Coventry as a structural engineer, where he worked until returning to Brussels in 1919. According to his future friend and partner Raphael Verwilghen, it was here that Eggericx acquired a taste for rational, utilitarian architecture. Eggericx became completely imbued with English culture, evidenced by the fact that he married Cambridge language professor Helen Thompson on April 11, 1917. When they returned to Belgium in 1919, friends and colleagues couldn't help but notice his almost total conversion to an English gentleman. (Culot, p. 59).

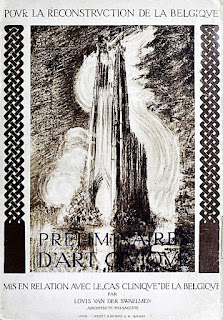

Left: Louis Van der Swaelmen, date unknown. Right: Preliminaries d'Art Civique by Louis Van der Swaelmen, Societe D'Editions, Leyde, 1916. Front cover.

Belgian landscape and architect-city planner Louis Van der Swaelmen spent the War years in Holland and was part of a study group known as the Comité Néerlando-Belge d'Art Civique, with fellow Belgians Herb Hoste, future Le Corbusier client Paul Otlet, and four Dutchmen, Hendrik Berlage, Petrus Cuypers, Evers, and Pauw, with Berlage acting as the chairman. Direct contact with Berlage provided a considerable stimulus. (Culot, p. 61).

Left: Schematic diagram of the theoretical concentric aggregation of a city and the emergence of the permanent and universal constituent elements of the notion of city. Plate published in Préliminaires d'Art Civique, Louis Van der Swaelmen, 1916. (Culot, p. 60). Right: "Organisation de la Cooperation Internationale a l'Etede de la Reconstruction less Cites Detruites ou Endommagees par la Guerre de 1914 en Belgique," Ibid.,

In 1916, Van der Swaelmen published a 300-page post-war reconstruction manual,

Préliminaires d'Art Civique, in which he developed a theory of urbanism that could serve as a handbook for a future city planning philosophy. He presented a diagram of the city as a biological organism delineating the different functional elements of its "organs." (See above and also 'Nature's Offensive': The Sociobiological Theory and Practice of Louis Van der Swaelmen, by Koenraad Danneels, Journal of Landscape Architecture, 14:3, pp. 52-61).

Left: La Cité, Vol. I, No. 1, July 1919. Front cover. (Culot, p. 61). Right: Ibid., first issue masthead.

After the war ended, Van der Swaelmen and Verwilghen collaborated to found a new journal, La Cité, to trumpet their ideas of reconstruction and garden cities. In the first issue, Verwilghen opened with a three-page article outlining his vision, an excerpt of which follows.

"La Cite will broadly consider a question touching on all areas of technical, industrial, and social activity, and will strive to be the crossroads of all currents of opinion in matters of public art." (Ibid., p. 1).

Verwilghen next published "Urban Planners from Foreign Countries Support Our Efforts," a three-page piece mysteriously signed by L. C., which included,

"The considerable work and so full of interest for the future of Belgium, which under the direction of our friend Van der Swaelmen, the Dutch-Belgian Committee of Civic Art has carried out there, could not have been completed without the sympathy and generous cooperation of Dutch intellectuals and especially of the eminent architect H.-P. Berlage." (Ibid., p. 5).

Berlage sent a letter of support to the editor, which read in part,

"...it is the interest which, in a general way, presents the problem of the construction of the modern town. Without a doubt, this question is still new, - but already before the war, the ideas that relate to it had become so precise that we have an exact notion of it and can define with certainty the direction in which these ideas are developing. And if we can now speak of a happy Belgium it is because it has become the first country which will be able to realize this exact notion of the construction of the modern town." (Ibid., p. 6).

Left: "S. U. B., Manifeste de la Société des Urbanistes Belges, La Cité, Vol. I, No. 3, September 1919, pp. 37-40. Right: "What needs to be rebuilt?" La Cité, Vol. I, No. 1, July 1919, p. 7.

Verwilghen and Van der Swaelmen were among the editorial signatories of the Manifesto for the newly formed Société des Urbanistes Belges (SUB), in which they also stated the definitions of their masthead titles of Architect, Engineer, and Landscape Architect. The Manifesto read in part,

"The SUB will be both a study circle and a militant group. Access to it will be possible for architects, engineers, landscape architects, who declare that they adopt the modernist profession of faith and the general principles formulated above, who have been admitted to the ballot of their peers and who have demonstrated their urban planning abilities: either that their work has been awarded a prize, retained or acquired at one of the major international urban planning competitions: either that they have carried out characterized urban planning works or that they are authors of remarkable urban planning projects or that they have proposed excellent solutions to the problem of Housing, -or that they have presented to the judgement of their peers a considerable thesis, or the equivalent thereof, which reveals the possession of extensive urban planning knowledge and general ideas on the subject." (Ibid., p. 38).

Left: Special Issue Dedicated to the Reconstruction Exhibition, La Cité, Vol. I, No. 4-5, November-December, 1919, front cover. Right: "Exposition de la Reconstruction, La Section Belge," Ibid., Planche IX.

In addition to Belgium, the countries of France, the Netherlands, and England participated in the big exhibition in Brussels' Egmont Palace from September 19th to November 1st. La Cité dedicated a special double issue to the event. Louis Van der Swaelmen organized the Belgian exhibits and contributed a seven-page in-depth article which compared programs of major nations and summarized the breadth of destruction throughout Belgium compared to neighboring countries, and also described the planning activities of his and Berlage's wartime"Dutch-Belgian Civic Art Committee" ("Les Sectiones Etrangeres d'Urbanisme Compare (Foreign Sections of Comparative Urban Planning)," by Louis Van der Swaelmen, Ibid., pp. 69-75).

Louis Van der Swaelmen first met the 22-year-old Victor Bourgeois at this exhibition. Of their meeting, Bourgeois wrote:

"I cannot emphasize enough the importance of this meeting overseen by Senator Vinck, which gathered the reporters Vander Swaelmen, Hoste, Verwilghen, Bodson, and Puissant, The agenda included reports on land policy, urban planning, normalization, and urban aesthetics. In brief, a synthesis of what urban planning and architecture should be." (Strauven, p. 50).

"A Belgian Urban Planner: Louis Van de Swaelmen," by Andre De Ridder, La Cité, March 1920, pp. 176-184.

La Cité's publicist, Andre De Ridder, contributed an eight-page piece in the March 1920 issue chronicling the exploits of fellow editor Louis Van der Swaelmen, including his books and various reconstruction committee efforts to bring readers of the journal up-to-date on his significant efforts in planning the foundation for Belgium's reconstruction.

Left: "La Maison Idéale," by J.-J. Eggericx, La Cité, April 1920, pp. 197-204. Right: "La Maison Ideale," C. J. Kay, Architect, Ibid., Plate XXI.

In the very next issue, Verwilghen published an eight-page article by Eggericx, "La Maison Idéale," which had previously appeared in the London Daily Mail. The Daily Mail conducted an annual extravaganza, the Ideal Home Exhibition, each spring in London's Olympia Exhibition Centre. While attending a Low-Cost Housing Conference in London, Eggericx also attended the Ideal Home show and found the time to prepare his detailed article. He illustrated his text with the plans, redrawn by himself, and focused on the many time-saving devices designed into the prize-winning home by architect C. J. McKay.

"The jury was composed of architects, experts, men of aesthetics and technology. It had the wisdom to also include the precious science of a person accustomed to presiding over the destinies of a household." (The Ideal Home," J.-J. Eggericx, London Daily Mail, March 1920).

Left: "La Nouvelle Croisade, L'Effort Anglais," J.-J. Eggericx, La Cite, December 1920, pp. 27-42.

Editor Raphael Verwilghen opened the December 1920 issue of La Cité with an article entitled "Improving Popular Housing in England," which was illustrated with a "Bristol City Extension Plan" map, which served as an introduction to a "travelogue given to us by the architect Eggericx...which once appeared in the [London] "Times." Eggericx's "The New Crusade" described an August "congress" tour of garden city developments in Bristol, Welwyn, Ealing, Ruislip-Northwood, Acton, Bournville, and Harebreaks Estate that he illustrated with maps and floor plans.

Through Louis Van der Swaelmen, Victor Bourgeois came into direct contact with the garden city movement in Belgium. It was also likely that through Van der Swaelmen that Bourgeois was offered a job at the Société Nationale d'Habitations et Logements a Bon Marché (National Society for Affordable Homes and Lodgings - SNHLBM) in April 1921, where he remained until October 1922. Without this initial experience, Bourgeois most likely would not have undertaken the adventure of designing the now iconic Cité Moderne.

Bourgeois witnessed the 1922 beginning of the Le Logis-Floreal garden city development by Eggericx and Vander Swaelmen, and was also keeping a close watch on the outcomes of an experimental SNHLBM building site in the La Roue neighborhood, also headed by Eggericx. In 1922, Van der Swaelmen and Bourgeois drew up the urban development plan for Cité Moderne. (Strauven, pp. 49-54).

Left: "La Maison Bourgeoise Idealle, Resultats du Conciurs pour 1922 du Daily Mail," by J. J. Eggericx, La Cite, Vol. III, No. 3, March 1922, pp. 51-58 and 2 plates.

Verwilghen again published the results for the 1922 London Daily Mail Ideal Home Competition, a ten-page article that J. J. Eggericx originally published in London. Eggericx would soon join Verwilghen on La Cité's editorial masthead and also become his architectural partner.

Left: Victor and Pierre Bourgeois, 1920. Photographer unknown. Right: Inaugural issue of 7 Arts, June 1922. (Strauven, p. 91).

Also, during the spring of 1922, the Bourgeois brothers formed the weekly newsletter 7 Arts. The highly respected avant-garde magazine took its inspiration from Le Corbusier's L'Esprit Nouveau, which began in 1920. 7 Arts would enjoy a seven-year run.

7 Arts, Vol. 1, No. 1, June 1922. Strauven, p. 91. Right: "7 Arts," Victor Bourgeois, La Cité Vol. 3, No. 7, July 1922, pp. 147-8.

The inaugural issue of the Bourgeois brothers' 7 Arts appeared on the streets of Belgium on June 22, 1922. Its manifesto-mission statement was repeated in the July issue of La Cité along with another 7 Arts article from Bourgeois entitled "Architecture" ("Architecture," Victor Bourgeois, Ibid., p. 149).

"L'Exposition d'Architecture du Palais d'Egmont," by Charles Conrardy, La Cite, Vol. III, No. 6, June 1922, pp. 123-6 and Plates XI and XII. (Not in Langmead or Kathryn Smith's Wright on Exhibit).

Charles Conrardy, the librarian for the Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, contributed a six-page review of an exhibition organized by the International Congress of Architects at the Egmont Palace, which included "works, plans, elevations, sections, photographic views, and drawings of the Congress participants." He ended his critique with: "Frank Lloyd Wright is immortal in simple plans, in natural and calm lines, he created in a way a whole new way of building which does honor to the United States and to the world."

Left: "National Farmer's Bank, Owatonna, Minnesota, Louis Sullivan, Architecte, La Cite, July 1922, Plate I. Right: "Avery Coonley House, Riverside, Illinois, Frank Lloyd Wright, architect, Ibid., Plate IV. Not in Langmead or Kathryn Smith's Wright on Exhibit)

The July issue started with a ten-page article, "L'Architecture Americaine," also by Charles Conrardy. This article focused on the American section of the architectural exhibition at the Egmont Palace that he had reviewed the previous month. After some quite negative criticism of American architecture as a whole, he singled out Louis Sullivan and his disciple Frank Lloyd Wright for praise and included four illustrations. (Also, not in Langmead or Smith.)

Left: Ad for L'Art et la Société by H. P. Berlage, La Cité-Tekhne, Vol. III, No. 6, June 1922, p. 142. Right:

This June 1922 La Cité-Tekhne ran an ad for an H. P. Berlage book that combined his series of articles from Art et Technique, from September 1913 to February 1914. This inspired the Bourgeois brothers to establish their own publishing wing, L'Equerre, to publish Henry Van de Velde's 1916 "Formules Esthetiques d'Une Moderne" after serializing it in three consecutive issues in La Cité from February through April 1923. (See below for example.) Raphael Verwilghen soon added Bourgeois, Van de Velde, Berlage, Van Doesburg, and Le Corbusier to the list of contributors on La Cité's masthead. (Author's note: Victor Bourgeois first came into contact with Henry Van de Velde in 1920. Van de Velde was then back in Belgium from pre-war Germany. They met through an introduction from his brother Pierre, who had mutual connections at the Université Nouvelle. Pierre was also instrumental in Victor being named a professor at Van de Velde's new La Cambre in 1927, despite being only 29 years old. (Strauven, p. 30).

Left: "A Few Words of Introduction to The Formulas of a Modern Aesthetics by Henry Van de Velde," by Victor Bourgeois, La Cité, Vol. III, No. 10, February 1923, pp. 209-213 and four plates. Right: "Suite d'idees pour un conference," by Henry Van de Velde, Ibid., pp. 214-221.

Bourgeois announced at the end of his first February installment,

"The Formulas of a Modern Aesthetic by Henri van de Velde will soon be published by L'Equerre. We have obtained the favor of being able to offer our readers the first look at the most remarkable pages of this volume. Furthermore, Mr. Victor Bourgeois has authorized us to deliver to the public the study that will serve as a preface to the Writings of the master."

Formules d'une Esthetique Moderne by Henry Van de Velde, L'Equerre, Brussels, 1923, front and back covers.

The Bourgeois brothers formed their own 7 Arts publishing wing, L'Equerre, and strategically made Van de Velde's Formules d'une Esthetique Moderne their first publication.

Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar 1919-1923, (Exhibition catalogue for Weimar State Bauhaus, 1919-1923), cover design by Herbert Beyer, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (layout designer-coeditor), Walter Gropius (coeditor), 1923.

Left: Staatliches Bauhaus Ausstellung, 1923 Gift of Walter Gropius. Poster design by Joost Schmidt, 1923. Courtesy MOMA Archives. Right: Staatliches Bauhaus 1923. Photograph by Herbert Bayer. One of the major early events in the modernism movement was an exhibition at the Bauhaus in the fall of 1923. Walter Gropius wrote to Mies van der Rohe on June 14, 1923, after viewing his models on display at the 'Große Berliner Ausstellung,' which opened in May. He invited him to contribute to the 'Internationale Architektur' section of the first major Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar, from August 15 to September 30, 1923. On June 21st, Mies happily agreed to contribute three models to the show. It was at this exhibition that Siegfried Giedion first met Walter Gropius, marking the beginning of a lifelong relationship. Giedion wrote one of his first reviews on this exhibition and had it published in the

September 1923 issue of Das Werk, which Albert Frey may have seen

. (From Mies van der Rohe, An Architect in His Time, by Dietrich Neumann, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2025, p. 78. Author's note: In 1907, Henry Van de Velde established the Grand-Ducal School of Arts and Crafts under the patronage of the Grand Duke. Van de Velde designed the school's building and was the school's first director. He stepped down during World War I due to his Belgian citizenship and suggested that architect Walter Gropius succeed him. In 1919, the School merged with the Weimar Art Academy to form the famous modernist art school, i.e., the Bauhaus.)

Left: Catalogue for the Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung, 1923, Office Building, Mies van der Rohe, High-rise for the Chicago Tribune by W. H. Luckhardt. pp. 30-31. Right: Bauhaus Exhibition, International Architecture Section, Models of the Curvilinear Glass Skyscraper and Concrete Office Building by Mies van der Rohe to the left and Walter Gropius's Chicago Tribune Tower competition design entry. Photo from the exhibition at the Bauhaus Museum Weimar.

Siegfried Giedion met Walter Gropius for the first time at this exhibition and enjoyed an ongoing collaboration throughout the 1920s and 1930s via the CIAM congresses and other get-togethers.

Le Stand de L'Equerre-7 Arts, Salon de la Lanterne Sourde, 7 Arts, December 1923.

Victor Bourgeois first publicized the formation of L'Equerre in a December 1923 issue of 7 Arts with a photo of the stand at the Modern Architecture and Decorative Art Exhibition at the Egmont Palace. La Cité publicized the same exhibition in its December issue, leading off with two reviews. The first was a quite lengthy 20-page piece illustrated with ten plates by Hyppolite Fierens-Gevaert, the curator of the Royal Museum of Belgium.

“Victor Bourgeois is also a clear-sighted critic and a bold director. Editor-in-chief of the weekly magazine 7 Arts, his articles on standardization, monolithic constructions, doors and windows, etc., have the air of a credo. His works illustrate this: individual houses, semi-detached or grouped by four or six, beautiful only through an intelligent distribution of volumes and the harmony of opposing forces: solids and voids. J. Eggericx, in his garden cities of Watermael and Comines, pushes severity to the point of puritanism."

Left: "L'Architecture et l'Art Decoratif Modernes en Belgium," by Hyppolite Fierens-Gevaert, La Cité, Vol. IV, No. 6, December 1923, pp. 93-133 and 10 plates. Right: "Urban development project for the District of Jemet by Victor Bourgeois, Ibid., plate VI.

Fierens-Gevaert began his article by comparing the states of modernism in France and Belgium and reminding readers of the historical contributions of Victor Horta and Henry Van de Velde. He included a section on new aesthetics on low-cost construction and favorably mentioned Verwilghen as "being the soul of a beautiful magazine, La Cité, and Van de Swaelmen's book Preliminaires d'Art Civique and numerous garden city layouts, including Cité Moderne, Trois-Tilleuls, and Floreal in Boitsfort, Selzate, Kapelleveld, collaborating with architects Victor Bourgeois, J. J. Eggericx, Huib Hoste, and others. He also singled out Victor Bourgeois and J. J. Eggericx, of whom he wrote:

"Victor Bourgeois is also a clear-sighted critic and a bold director. Editor-in-chief of the weekly magazine 7 Arts, his articles on standardization, monolithic constructions, doors and windows, etc., have the air of a credo. His works illustrate this: individual houses, semi-detached or grouped by four or six, beautiful only through an intelligent distribution of volumes and the harmony of opposing forces: solids and voids. J. Eggericx, in his garden cities of Watermael and Comines, pushes severity to the point of puritanism."

Left: "The Stand of L'Equerre," Ibid., Planche VIII. Right: "Exhibition of New Spirit Belgian Arts at the Egmont Palace, Plan of the L'Equerre-7Arts Stand."

by Charles Conrardy, Ibid., pp. 113-115.

In the same issue, Charles Conrardy contributed a three-page article reiterating the fine qualities of the work of Eggericx and Van der Swaelmen at Trois-Tilleuls and Kappeveld and included a plan of the architectural exhibition behind the L'Equerre-7 Arts stand.

Left: Vers Une Architecture by Le Corbusier, Cres, Paris, 1923. First edition. Right: "Vers Une Architecture," book review by Charles Comardy, La Cité, Vol. 4, No. 9, April 1924, pp. 166-173.

In April 1924, the librarian for the Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, Charles Conrardy, contributed a seven-page book review of Le Corbusier's seminal Vers Une Architecture. Presaging that they would soon include Le Corbusier and Conrardy on the masthead as contributing editors, Verwilghen included:

"We are pleased to announce to our readers that Mr. Le Corbusier has included in a forthcoming issue of our Review some essential pages of his book. This publication will be accompanied by numerous photographs."

In December 1924, La Cité editor Verwilghen added Le Corbusier, Victor Bourgeois, H. P. Berlage, Charles Conrardy, J. J. P. Oud, Henry Van de Velde, Theo Van Doesburg, Jozef Peeters, Maurice Casteels, Andre de Ridder, Fierens-Gevaert, and others to the journal masthead as collaborators. Raphael Verwilghen published an article he had presented at the International Conference on City Planning in Amsterdam last July. "Transport According to the Regional Plan" was a sixteen-page piece illustrated with charts and diagrams of varying modes of transportation relevant to his expertise as a "civil construction engineer". He followed that with a two-pager, "The Fate of Garden Cities in England," describing a tongue-in-cheek article he had recently read in Garden Cities and Town Planning. The next month, he added the firm's draftsman, Ewaud van Tonderen, to the list of La Cité's collaborators. The following September, he would be joined in his atelier by Albert Frey.

The Belgian Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, 1925, Victor Horta, architect.

Left: Poster for the 'Internazionale delle Arti Decorative' in Monza, May to October 1925. Poster design by Giovanni Guerrini. Right: Abstract art stand at the 'Biennale delle Arti Decorative' in Monza, with chairs, a cabinet, and a table designed by Victor Bourgeois, 1925. (Strauven, p. 126.

When it was clear that the miniature garden district and the stand devoted to the artistic press were not going to be included in the 1925 Paris Exposition, Fierens-Gevaert commissioned Victor Bourgeois to design a 'Stand for Abstract Art' for the 'Internazionale delle Arti Decorative' in Monza. Bougeois collected pieces from his 7 Arts colleagues Jean-Jacques Gaillard, Karl Maes, Jozef Peeters, Pierre-Louis Floquet, and Victor Sevranckx to produce a multi-colored interior using their visual works combined with furniture of his own design. (Strauven, p. 126. See also "La participation belge a l'Exposition International des Arts Decoratifs de Monza (Italie)", 7 Arts 4, no. 3 (1 November 1925), p. 1.

Left: Belgian Modernist Architecture Since the War. Modern Garden Cities in Belgium, La Cité, August 1925, Plate V. Right: "Project of a Garden City in Belgium," unbuilt. Photo from 7 Arts Journal. Ibid., Plate II.

The Belgian contingent of modern architects at the 1925 Paris Expo held court at the "Galerie Esplanade de Invalides" as described in a map in the August 1925 issue of La Cité. A passage from Le Corbusier's Vers Une Architecture accompanied the map:

"A perfect urban cycle is only accomplished when it reaches the culmination of any complete period of urbanization: the urban landscape characterized by an Architecture. The third dimension in urbanization, architectural elevation, gives rise to the urban landscape, conditioned by the organic generating plan. "We use stone, wood, cement, glass: we make houses, palaces from them: it is construction ." My house is practical. Thank you, as thank you to the railway engineers and the Telephone Company. You have not touched my heart. But the walls rise to the sky in such an order that I am moved by them... My eyes are looking at something that states a thought. A thought that is illuminated only by prisms that have relationships between them. These prisms are such that light details them clearly... They are a mathematical creation of your mind. They are the language of architecture. (Le Corbusier)"

Left: Almanach D'Architecture Moderne, Le Corbusier, Cres Editions, Paris, 192^. From Le Corbusier, Architect of Books, Catherine De Smet, Lars Muller Publishers, Baden, 2005, p. 27. Right: Pavilion de L'Esprit Nouveau, Paris, 1925, Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, L'Architecture Vivante, Winter 1925, p. 48.

Siegfried Giedion viewed Le Corbusier's Pavilion and met him for the first time at the Paris Exposition. The encounter influenced him so much that he focused his 1928 book, Bauen in Frankreich, Bauen in Eisen, Bauen in Eisenbeton, on France, sketching the outline of a development that culminated in deep coverage in the work of Le Corbusier. ("Siegfried Giedion: A Biographical Sketch," by Sokratis Georgiadis in Building in France, Building in Iron, Building in Ferro-Concrete, by Siegfried Giedion, Getty Center, 1995, pp. 226-7).

Left: L'Art Decoratif d'Aujourd'hui, Le Corbusier, Cres, Paris, 1925. Center: La Peinture Moderne, Ozenfant and Jeanneret, Cres, Paris, 1925. Right: Urbanisme, Le Corbusier, Cres, Paris, 1925. (All in Le Corbusier et le livre, Fondation Le Corbusier, 2005, pp. 103-5)

Le Corbusier published three books in conjunction with the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925. The books were, in essence, extracts reprised from issues 18-28 of L'Esprit Nouveau. As a group, they represented the essence of Le Corbusier's philosophy to the present time."The Belgian Garden City in Miniature," by Victor Bourgeois, 7 Arts, Vol. 3, No. 17, February 26, 1925, p. 1.

Left: "l'Exposition de Paris," 7 Arts, Vol. 3, No. 24, April 30, 1925, p. 1. Right: "Special Issue Dedicated to the Modern City," by Victor Bourgeois, 7 Arts, Vol. IV, No. 1, October 15, 1925.

Victor Bourgeois also published much coverage of the Paris Exposition in 7 Arts, including the grand prize in architecture for his Cité Moderne project in the above October 15, 1925, special issue.

Left "Projet de Cité-Jardin Belge by Les Urbanistes: Van der Swaelman, Verwilghen, Les Architectes: Bourgeois, Eggericx, Hoste, Hoeben, Pompe, Rubbers," from "L'effort moderne en Belgique" by Louis Van de Swaelman, La Cité, Vol. V, No. 7, August 1925, Planche I, pp. 124-143. Right: "Pavilion de L'Esprit Nouveau" a L'Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs 1925, Le Corbusier et P. Jeanneret, L'Architecture Vivante, Winter 1925, p. 48.

A model of a Belgian garden city was also on display at the Paris Exposition, which was originally intended to be built to full scale, similar to Le Corbusier's Pavilion L'Esprit Nouveau. But the powers that be ruled that no trees could be destroyed. That is likely why so many trees are evident in the Belgian architects' maquette seen above. Le Corbusier resolved that issue by creatively incorporating his intrusive tree into his design. (See above right).

Left: "Maquette d'un des pavilions projetes, Architecte: J.-J. Eggericx, (Bruxelles), Ibid., Planche III. Right: Maquette du Stand de la Societe des Urbanistes et Architectes Modernistes - Ce stand est realiste et see trouve dans un des Halls de l'Esplanade des Invalides," Ibid., Planche IV.

"Another aborted project, planned by a group of architects and urban planners who had already built garden cities, and composed of Van der Swaelmen, Verwilghen, Bourgeois, Eggericx, Hoste, Hoeben, Pompe, and Rubbers, to build a mini garden city on the Esplanade des Invalides, composed of six low-cost houses. The constraint of trees spaced less than 5 meters apart in all directions and the obligation to build with lightweight, exhibition-grade materials limited the project, according to an article from the time, to an architectural event showing that in Belgium, too, as in certain other European countries, the beginnings of a sui generis contemporary domestic architecture linked to the current major international trend toward volume architecture were being revealed.¹ Lacking the support of the building and furniture industries, the project never saw the light of day

Ultimately, Eggericx's participation was limited to a few panels presented in the section of the Belgian Society of Modernist Urban Planners and Architects in the Architecture Gallery located on the Esplanade des Invalides. The panels are composed of photographs and drawings enhanced with gouache and present different aspects of garden cities and low-cost houses, the outline of the facade for Claire Petrucci's house, and the preliminary design of the children's home in Bredene-sur-Mer." (Culot, p. 188).

Left: Projeta de maisons economiques, section Belge a l'Exposirion Internationale de Paris, 1925, perspectives reehaussees a la gouache. (From J.-J. Eggericx, Gentleman Architecte, Createur de Cites-Jardins edited by Maurice Culot, AAM Editions, 2012, p. 8). Right: Home des Enfants du Hainaut, Bredene, 1925, axonometrie et facades. (Culot, p. 166).

One of the big projects then on the drawing boards of Eggericx & Verwilghen was the Home de Enfants du Hainaut in Bredene, which began in 1925. Preliminary renderings were included in the Paris Expo, and construction began soon after Frey arrived in Brussels. He contributed to the legions of construction drawings and details that were necessary.

Left: "Le Home des Enfants du Hainaut A-Breedene-Sur-Mer, Architecte: J. J. Eggericx. La Cite, Vol. VI, No. 3, October 1926, pp. 33-36 and 6 plates. Right: "Le Home des Enfants du Hainaut" children's dormitories." Culot, p. 170.

The project was completed in 1926 and appeared in La Cité in the October issue. It included numerous elements which would prove useful to Frey in his work on Le Corbusier's Arsile Flottant, which will be described later below.

Left: "Architecture en Belgique," Rear Facade of the Villa Vanden Perre, Uccle 1925-6, J. J. Eggericx, architecte, La Cité, Vol.VII, No. 5, October 1928, pp. 68. Right: Villa de Robert Vanden Perre, Uccle, rendering by Ewaud van Tonderen. From Culot, p. 83.

Eggericx began designing the Villa de Robert Vanden Perre right as Albert Frey entered his atelier in the fall of 1925. The eaves contained elements of Frank Lloyd Wright, and the rear facade was basically ornament-free with clean modern lines. Albert Frey's atelier-mate Ewaud van Tonderen produced the above-right 1925 rendering. Eggericx did not publish anything on the house until his October 1928 article in La Cité, for which the editor praised his clean design with,

"This facade, where one finds neither ornamentation, nor brick projections, nor play of volumes, no eccentricity of lines, no search for amusing or bizarre effects, is pure architecture."

Left: "Numero Special Consacre a la Cité Moderne, 7 Arts, Vol. IV, No. 1, October 18, 1925, p. 1. Right: La Cité Moderne, Berhem-Sainte-Agathe, Brussels, 1922-25, Victor Bourgeois, architect. Photo by Duquenne. (Rassegna 34, p. 46)

Bauen, Der Neue Wohnbau by Bruno Taut, Klinkhardt Biermann, Berlin, 1927. Dust jacket illustrating Victor Bourgeois's Cité Moderne.

The same month Albert Frey began working with Eggericx & Verwilghen, Victor Bourgeois published a special issue of 7 Arts dedicated to the Cité Moderne, which included the same photo on the cover that Hannes Meyer had included in Das Werk the previous month. The iconic photo also later appeared on the dust jacket cover of Bruno Taut's Bauen, der Neue Wohnbau, among numerous other publications.

Announcement of Victor Bourgeois Lecture, "Le Beau par l'Utile," (Beauty through Usefulness), December 1925. From "L'ideologia del modernismo belga dopo l'Art Nouveau," by Francis Strauven in L'architettura in Belgio, 34 Rassegna, Milan, 1979, p. 6.

Near the end of 1925, La Cité included the third of a four-part series on the 1925 Paris Exposition, a ten-page article by Charles Conrardy. It also announced a lecture series featuring Victor Bourgeois and Louis Van der Swaelmen at Victor Horta's Maison du Peuple in Brussels, which Albert Frey almost certainly would have attended.

Left: Maison du Peuple, Brussels, Victor Horta, architect, 1899. Right: Belgian Workers' Party Auditorium inside the Maison du Peuple.

Maison Pettrucci-Wolfers, Brussels, 1925-6, J.-J. Eggericx, architect, displayed in the 1925 Paris Exposition. (Van Loo and Matteoni, Rassegna 34, p. 75).

Another important project in the Eggericx atelier on Albert Frey's arrival was the Maison Pettruci-Wolfers. A rendering for the project completed in January 1925 by Ewaud van Tonderen was displayed at the 1925 Paris Exposition and won a prize for Eggericx. A dispute with a neighbor on the aesthetics of the project caused a delay in construction until Eggericx commissioned Victor Horta to mediate facade details in March 1926. Since this was after Fey began work with Eggericx, he may have been involved in the preparation of construction drawings and detailing. (Culot, p. 147).

Left: Rendering and front elevation of the Verwee-Lefebure Building, Brussels, November 1925, J.-J. Eggericx, architect. (Culot, p. 171). Right: Ibid., p. 159.

In November 1925, Eggericx began designing and constructing a duplex for Emma Verwee and Emma Lefebure. As design was wrapping up in May of 1926, they toured with Eggricx his project in Watermael-Boitsfort, mainly to help choose the type of Belvedere bricks. The final plans were approved in November 1926, and construction was completed in early 1927. It is likely that Albert Frey again had a role in preparing construction drawings and details.

(Culot, p. 158)."Belvedere" Bricques ad, Rendering of Fer a Cheval by J.-J. Eggericx, La Cité, Vol. VI, No. 5, January 1927, p. 57.

Eggericx put Albert Frey to work on construction drawings and details for his Fer a Cheval project in Watermael-Boitsfort sometime in 1926. This project was published in much more detail in La Cité in 1930, as seen later below. The project rendering seen in the above January 1927 La Cité Belvedere Bricques ad was again drawn by Frey's atelier-mate Ewaud van Tonderen. Frey returned to Zurich the following month to work and save money for his fateful period in the atelier of Le Corbusier in Paris. (Rosa, p. 14).

"Modern Propaganda," Slide Lecture by Victor Bourgeois at the University of Liege, Mines Exploitation Room, 5:00 p.m., March 12, 1926, 7 Arts, No. 20, February 28, 1926, p. 1. Also on March 10th at the British Tavern, 8:30 p.m., Conference on Modern Architecture sponsored by the Western Renaissance, Ibid. From 7 Arts (1922-1928) by Ronny Van de Velde, Colophon, 2017, p. 43.

In late February 1926, 7 Arts announced on the front page a slide lecture by Victor Bourgeois on the lessons of the International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, organized by the Cercle des étudiants & Proscenium with the assistance of the Anthologie Group. Also mentioned was a March 10th Collective Conference on Modern Architecture at the British Tavern featuring work by Victor Bourgeois, Raphael Verwilgen, and Louis Van de Swaelmen. Again, Frey would almost certainly have been in attendance.

Left: Announcement for two lectures of Le Corbusier in Brussels on 4 and 5 May 1926. (Strauven, p. 129). Right: "Pensee," by Le Corbusier, La Cité, Vol. VI, No. 3, September 1926, p. 38.

The Bourgeois brothers invited Le Corbusier to Brussels to give two lectures in early May 1926. The first was a slide lecture on his Plan Voisin of Paris, which La Lantern Sourde organized at the Institut des Hautes Etudes (Université Nouvelle). Victor Bougeois was one of the founders of the Lanterne Sourde in 1923. Since he was also listed as one of the editorial collaborators of Verwilghen's La Cité since December of 1924, it seems almost certain that Verwilghen's employee, Albert Frey, was also in attendance, as was Jean Canneel-Claes, future 1929 Le Corbusier client for an unbuilt house in Brussels and future 1929-30 J. J. Eggericx student at La Cambre. Attendance at these lectures would have cemented in Frey's mind his desire to eventually move to Paris to study at the feet of the master. ("Belgian Modernism: Themes and Projects," edited by Anne van Loo and Dano Matteoni. From 34 Rassegna, Architecture in Belgium, 1920-1940, Milan, 1979, p. 76. Between Garden and City: Jean Canneel-Claes and Landscape Modernism, Dorothee Imbert, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009, p. 30).

An excerpt from "Architecture III, Pure Creation of the Mind," of Le Corbusier's book Vers Une Architecture, was reprinted in La Cité in September, entitled "Thought." It read,

"We put stone, wood, cement into work; we make houses, palaces; it's work. But, suddenly, you make me feel good, I'm happy, I say: it's here. My house is practical. Thank you, like thank you to the railway engineers and the Telephone Company. You haven't touched my heart. But the walls rise to the sky in such an order that I am moved. I feel your intentions. You were gentle, brutal, charming, or dignified. Your stones tell me. You attach me to this place, and my eyes look. My eyes look at something that states a thought. A thought that is illuminated by prisms that have between them are such that the light details them. It has nothing to do with anything necessarily practical, a mathematical creation of your mind. They are the language of architecture. With raw materials, utilitarian that you overflow, you are moved. That is architecture." (See above right).

Albert Frey would most likely have read this excerpt just a few months after hearing Le Corbusier's Plan Voison de Paris lecture in Brussels, which undoubtedly reinforced his dream to apprentice with the master.

"Concours, Societe des Nations," La Cite-Tekhne, Vol. VI, No. 6, July 1926, p. 9.

A design competition for a Palace for the League of Nations in Geneva was announced in the July 1926 issue of La Cité. The site, located on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, was described in glowing terms, and the project's requirements were outlined. A sum of 165,000 Swiss francs is made available to the Jury to be distributed among the best projects presented. The prize money was broken down as follows: "First prize, 30,000 francs; 2nd prize: 25,000 francs and 23,000 francs; 3rd prize: 20,000 francs; 4th and 5th prizes: 15,000 francs; 6th and 7th prizes: 5,000. 25,000 francs will be distributed in mentions."

The December issue of La Cité contained an update on the Geneva Palace of the League of Nations design competition, reporting on a field trip to the site organized by the Société Centrale d'Architecture de Belgique and the reprinting of a letter of protest by Bruno Taut complaining about the short amount of time allowed before the entries were due in late January of 1927.

At his November lecture in Zurich, Corbusier recruited two of Karl Moser's students, Ernest Schindler and Walter Schaad, to join his team for the League of Nations in Paris, which he would establish in December. Two more Moser students, Hans Neisse and J. J. Dupasquier, and Zvonimir Kavuric from Yugoslavia, joined the team in late December, and were followed by Alfred Roth on January 5th. Roth was already in Paris when he was accepted to study art at the Bauhaus, but he chose to remain with Le Corbusier. ("Corbusier's Lectures in Zurich," Das Werk, December 1926, p. XXX, and "Der Wettwerb, die Projektbearbeitung und Le Corbusier Kamps um sein preisgekrontes Projekt," by Alfred Roth in Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret das Wetttbewerbsptojekt fur den Volkerbundpalast in Genf, 1927, by Werner Oechslin, Amman Verlag, Zurich, 1988.

Le Corbusier convinced his mother to attend his two lectures in Zurich, and after his return to Paris, he wrote,

"You may not imagine how happy I was to be with you in Zurich, and of course, I was so happy that my second lecture went off well and you had nothing to blush for. I was very touched by the testimonials of respect and sympathy that you provoked. Your attitude and your lovely expression of Corbusier's old mother made respect flourish all around you." (Letter to mother, November 29, 1926, Paris. Weber, p. 244).

In connection with Corbusier's November 1926 lectures, Josef Gantner took the opportunity to republish the December 1926 issue of Das Neue Frankfurt's article on Corbusier's Pessac project. Frey had just missed viewing in person the November 24th lecture at the Zurich Institute of Engineers on the Plan Voisin and the 25th at the Zurich branch of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, which turned out to be a three-hour tour de force "on the rationalist and radical elements of architecture that Corbusier writes about in his books." ("Die Neuen Wohnviertel Fruges en Pessac (Bordeaux)," Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, architecten, Das Neue Frankfurt, Vol. 13, No. 12, December 1926, pp. 30-32. Author's note: Siegfried Giedion published an article in the February 1927 issue of Der Cicerone in Berlin (see below) that featured ten pages of Le Corbusier's work, mostly on Pessac.)

Bauhaus No. 1, December 1926.

Walter Gropius published the inaugural number of his new Bauhaus journal in Dessau in December 1926. The newsletter continued to be published quarterly until late 1931. The newsletter made Bauhaus life seem so appealing that Alfred Roth, a former Swiss architecture student of Karl Moser, then working in his Zurich atelier, immediately submitted an application to study art. In the meantime, Moser informed Roth that he had no more work and advised him to join Le Corbusier in Paris to work on his League of Nations design entry. Shortly after arriving in Paris, Roth's Bauhaus application was accepted, and he was then faced with a tough choice: either remain with Le Corbusier's League of Nations design team or go to Dessau to study painting. He chose the former. (Roth, p. 21).

League of Nations competition team, January 24, 1927; from left to right: Ernest Schindler, Hans Niesse, Walter Schaad, Alfred Roth, J. J. Dupasquier, Zvonimir Kavuric, Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier. From "Der Wettwerb, die Projektbearbeitung und Le Corbusiers Kampf um sein preisgekrontes Projekt," by Alfred Roth, p. 20, in Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret das Wetttbewerbsptojekt fur den Volkerbundpalast in Genf, 1927, by Werner Oechslin, Amman Verlag, Zurich, 1988).

S.d.N. 14, Axonometric view from the lake, January 1927. (Oeschlin, p. 46).

Le Corbusier was making an earnest effort to win the competition by assembling a design team of recent architecture students, mainly former students of Karl Moser from his home country of Switzerland. Moser was, coincidentally, also one of the competition's jury members. While in Zurich in late November on a brief lecture tour, Le Corbusier made an impassioned plea to Moser, seeking any former students who would be willing to take part in the design. Besides current employee Alfred Roth, Moser was able to round up former students, Hans Neisse, Ernst Schindler, Walter Scaad, and J. J. DuPasquier, who all reported for duty in Paris from mid-to late December. The group burned plenty of midnight oil to barely meet the design deadline of January 25th. The only compensation the team received for their heroic duty was train fare for the journey home and two warmly inscribed copies of Vers Une Architecture and L'Art Decoratif d'Aujourd'hui. (From Begegnung mit Pionieren by Alfred Roth, Birkhauser, Basel, 1972, p. 25 and Oeschlin, p. 20).

Left: Vers Une Architecture, Editions Cres, Paris, 1923. Right: L'Art Decoratif D'Aujourd'hui, Editions Cres, Paris, 1925.

Left: Kommende Baukunst (Vers Une Architecture), by Le Corbusier, Deutsche Verlags Anstalt, Stuttgart, 1926. Right: Ad for Kommende Baukunst by Le Corbusier in Cicerone, Vol. XIX, No. 14, August 1927, p. VI. (Author's note: Siegfried Gideon was named architectural editor for Cicerone in January 1927 based on his series of three articles starting in January through April, which were excerpts of his upcoming Frankreich book published in June 1928.)

Later that year, in nearby Antwerp, Le Corbusier designed a house-studio for artist

René Guiette, who had seen his Pavilion de l'Esprit Nouveau at the Paris Exposition the previous year. Since the house was not completed until mid-1927, it is unlikely that Albert Frey was able to view it before moving back to Switzerland in February 1927. He did, however, most likely see, and perhaps participate in some manner, in the design and construction of Eggericx's Villa L'Escale in La Panne on the Belgian Coast in 1926.

(See above right).

"Die Neuen Wohnviertel Fruges in Pessac (Bourdeaux)," Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Architects, Paris, Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 2, February 1927, pp. 57-58.

Albert Frey opened up the February issue of Das Werk in his first month back in Zurich and was taunted by an article on his idol's development of low-cost homes in Pessac near Bordeaux. The article led off with an expression of thanks to readers who had responded positively to the magazine's December plea for the appointment of Le Corbusier to a position at the Technical University of Zurich in anticipation of the looming retirement of the beloved Karl Moser.

"Zur Situation der Franzosischen Architektur II," by Siegfried Giedion, Der Cicerone, Vol. XIX, No. 4, February 1927, pp. 174-189.

While working for Eggericx and Verwilghen for over a year and a half, Albert Frey had time to become absorbed in Corbusier's writings and philosophy. He was convinced that he must find his way to Paris. But first, he needed to move back with his family in Zurich to build a nest egg he knew he would need for survival during his unpaid Le Corbusier apprenticeship. In February of 1927, Frey began working for the Zurich firm of Leuenberger & Fluckiger, where he again did detailing and construction drawings of traditional cooperative housing, but considered it only a brief detour on his journey to Paris. (Rosa, p. 14).

"Mechanisierung und Typsierung des Serienbaues" and "De Zementblock-Bauweise von Frank Lloyd Wright," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, Issue No. 2, February 1927, pp. XXIII-XIV. Not in Langmead. (See also Wie Baut Amerika? by Richard Neutra, Die Baubucher, Band 1, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927, pp. 60-61. Not in Langmead.

During Frey's first month back in Zurich, the Swiss

Das Werk also published an excerpt from Richard Neutra's

Wie Baut Amerika regarding the cement block houses of Frank Lloyd Wright. The article was illustrated with construction photos of Wright's 1924 Storer House in Los Angeles. Kameki Tsuchiura, a Frank Lloyd Wright atelier-mate with Richard Neutra, took the images in 1924.

(See more at my "Taliesin Class of 1924, A Case Study in Publicity and Fame")

Left: Machine-Age Exposition catalogue, organized by Jane Heap, New York, 1927. Right: Poster for Machine-Age Exposition, 119 W. Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, May 16 to May 28, 1927.

While Albert Frey was back in Zurich,

Little Review co-editor Jane Heap organized an exciting exhibition called the Machine-Age, seemingly taking a cue from Le Corbusier's quote in his 1923

Vers Une Architecture, "A house is a machine for living in." Heap's closing paragraph in her catalogue introduction reads,

"The experiment of an exposition bringing together the plastic works of these two types of artist has in it the possibility of forecasting the life of tomorrow. All of the most energetic artists, both here and in Europe: painters, sculptors, poets, magicians, are enthusiastically organized to support this exhibition, the Engineers are giving it their interested cooperation."

Left: Project for Glass Skyscraper, Hugh Ferris, Ibid., p. 4. Right: Double House, Bauhaus, Dessau, Germany, by Walter Gropius. State Theater, Jena, by Walter Gropius and Adolph Meyer, Germany, Ibid., p. 25.

Albert Frey's colleagues from Brussels, Eggericx, Verwilghen, Victor Bourgeois (La Cité Moderne), Louis Van der Swaelmen, and many others all contributed work with which he was familiar, as did Le Corbusier with his Pessac project and other French work by Lurcat, Gueverkian, and Mallet-Stevens, Gropius with his Bauhaus, Knud Longberg-Holm, and much more.

Conceptual Concrete Parking Tower, unbuilt, 1927, designed by Albert Frey. (Rosa, p. 20).

While at Leuenberger & Flickiger from February 1927 to October 1928, Frey found the time to work on many personal projects and competitions to explore his own ideas and ready himself for the big move to Paris. One project was for a multi-story Concrete Parking Tower, and another was a Factory of Steel and Glass. He was attempting to produce some drawings that expressed Le Corbusier's architectural design elements to beef up his portfolio for his job interview. (See above and below.) (Rosa, pp. 20-21).

Conceptual Factory of Steel and Glass, unbuilt, designed by Albert Frey, 1927. (Rosa, p. 21).

"A Small House Group in La Jolla," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 4, April 1927, pp. XV-XVIII. From Wie Baut Amerika? by Richard Neutra, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927, pp. 52-57.

In April, Frey's long-term vision of moving to America was reinforced by yet another excerpt from Neutra's book in

Das Werk. This time, the article was "A Small House Group in La Jolla," on R. M. Schindler's Pueblo Ribera project, which also appeared in

Architectural Record two years later.

(Author's note: Schindler's Pueblo Ribera project was also published in A. Lawrence Kocher's Architectural Record in July 1930, the month before Albert Frey arrived in New York and began his partnership with Kocher. See more at my "A. Lawrence Kocher, Architectural Record, Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright, Albert Frey and the Evolution of Modern Architecture in New York and Southern California."Also, two of the projects Frey photographed during his 1932 trip to Los Angeles, besides the Olympic Stadium and MOMA's travelling International Style exhibition at Bullock's Department Store, were Neutra's Lovell Health House in Los Angeles and Schindler's Pueblo Ribera in La Jolla. Albert Frey Collection, UC-Santa Barbara)

Wie Baut Amerika?, by Richard Neutra, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927. Richard, Dione, and Frank Neutra next to R. M. Schindler at Kings Road, 1928. Photo by Jean Harris.

Le Corbusier also purchased Neutra's book and had a copy in his library when Frey finally joined the atelier in October 1928. (Le Corbusier et Livre, Exhibition of Le Corbusier's first edition books, COAC, Barcelona, 2005, p. 63).

Max Ernst Haefeli in the Girsberger & Co. Bookshop in Zurich in 1926. On display are Mendelsohn's Amerika and the exhibition catalog for the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition and Die Bühne im Bauhaus. From Anatomy of the Architectural Book by Andres Tavares, Canadian Center for Architecture, Lars Muller, Publishers, Zurich, 2016, p. 60.

Albert Frey would most certainly have spent much time browsing through the Girsberger bookshop in Zurich, both before and after his first stint in Brussels. Mendelsohn's Amerika and Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika? were both strong attractions he had in mind on his first trip to Paris in the fall of 1928. (Rosa, p. 17).

"Die Antoniuskirche in Basil," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 5, May 1927, pp. 131-138, 161-2..

Karl Moser's impressive, raw-reinforced concrete Antoniuskirsche in Basel was the next modernist project to appear in the pages of Das Werk in the May issue. Frey most certainly viewed the now iconic structure in person after its completion.

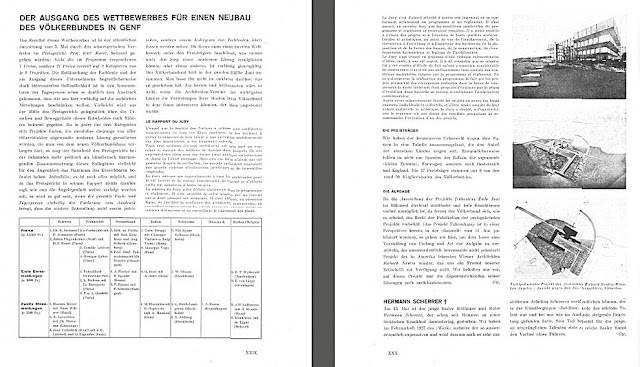

"The Outcome of the Competition for a New Building for the New League of Nations in Geneva," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 5, May 1927, pp. XXIX-XXX.

The May 1927 issue of Das Werk also announced the results of the controversial Palace of the League of Nations design competition. Although the jury was unable to name a winner that would move forward to construction, it awarded a total of 27 prizes. Le Corbusier was awarded a first prize, and Hannes Meyer a second prize. It also stated that the total of 27 prize winners represented around fifty members of 8 countries in the European Union. Josef Gantner further explained the illustrations of Richard Neutra's entry without crediting his partner, R. M. Schindler:

"We reproduce here, in order to give the reader an idea of the nature of the task, the extraordinarily interesting, non-award-winning project by the Viennese architect Richard Neutra, who lives in America, which a friend of our magazine has made available to us." (The incident is thoroughly discussed in Hines, pp. 71-2)

Internationale Neue Baukunst by Ludwig Hilbersheimer, Julius Hoffmann, Stuttgart, 1927, front cover and "Palace of the League of Nations, Geneva, Richard Neutra and R. M. Schindler, Architects, Ibid., p. 9.

Upon seeing the article in

Das Werk, Werner Moser immediately notified Schindler of the faux pas of his not being credited. Neutra was chagrined by his Swiss father-in-law, Alfred Niedermann, omitting Schindler's name from the submittal to Gantner, and ensured that his name was added to the photo caption in Ludwig Hilbersheimer's 1927

Internationale neue Baukunst, the second book following Neutra's

Wie Baut Amerika? in publisher Julius Hoffmann's Bau-Bücher series.

(See more on Moser, Neutra, and Schindler in my "Taliesin Class of 1924". For an excellent analysis of the League of Nations design competition, see Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture by Thomas Hines, Oxford University Press, New York, 1988, pp. 70-72 and endnote 6.

"The Competition for Building the Palace of the Society of Nations in Geneva," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 6. June 1927, pp. 163-171.

Le Corbusier's League of Nations entry was spread across eleven pages of the June issue as a hue and cry began to arise over the lack of awarding him a commission to build the project. He would mount an ultimately unsuccessful continent-wide publicity campaign over the summer, leaving the construction of his two Weissenhof houses in the untested hands of his League of Nations design team member Alfred Roth.

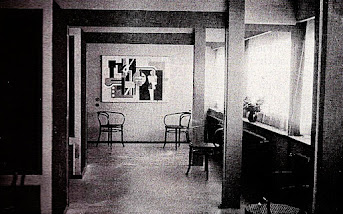

Left: Letter from Alfred Roth in Stuttgart to Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in Paris, July 27, 1927. From Le Corbusier Le Grand, edited by Jean-Louis Cohen and Tim Benton, Phaidon, New York, 2019, p. 188. Right: Living room on the ground floor of the double house, Weissenhof, Stuttgart, July 1927. Painting by Willi Baumeister. (Le Corbusier Le Grand), p. 192.

Albert Frey corresponded with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret by letter from the Weissenhof job site, bravely reporting progress and stating that the deadline for the opening of the exposition on July 23rd would be met. At the same time, he was compiling a book on the project that would be published in early September. The letter was written on stationery designed by Willi Baumeister, who would also provide paintings to stage the new units.

Award Ceremony at the League of Nations Palace, Geneva, 1927. From left to right: Victor Horta, Belgium (President), A. Muggia, Italy, Karl Moser, Switzerland, Ch. Lemaresquier, France, B. Attolico, Italy (General Secretary), Josef Hoffmann, Austria, J. Burnet, England, H. P. Brelage, Holland, Ch. Gato, Spain, and I. Tengbom, Sweden. From "Das Wettbewerbsprojekt fur den Volkersbund Palast in Genf," by Ernest Strebel. (Oeschlin, p. 97).

During May and June, an extensive letter-writing campaign took place between Moser and fellow judges on the panel and Le Corbusier and League officials. Modernists exploited this controversy with all the means at their disposal. (Oeschlin, p. 66).

Left: "The Powerful Liberator: Le Corbusier," by E. Henvaux, La Cité, Vol. 6, No. 9, June-July 1927, pp. 85-92 and VIII plates.

A major article by co-editor Emile Henvaux, "The Powerful Liberator," reviewing the reissue of Le Corbusier's

Vers Une Architecture, took up more than half the June-July 1927 issue and was well-illustrated with eight plates of illustrations of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles. An excerpt of Henvaux's praise reads,

"Le Corbusier's first writings appeared, as we know, a few years after the war, in the magazine "L'Esprit Nouveau," edited by Messrs. Ozenfant and Ch. E. Jeanneret. Those interested in contemporary aesthetic problems cannot forget the vitality and enthusiasm of L'Esprit Nouveau. They themselves know to what powerful extent this publication helped to liberate the plastic arts, literature, and music. For living architecture, L'Esprit Nouvea did even more, thanks to Le Corbusier."

The August 1927 issue of La Cité contained a report on the results of the judging of the 377 entrants to the "Concours Pour la Palais de la Société de Nations à Genève." The Belgian architects maintained that the jury did not respect the conditions of the contract governing the competition, and that this observation is all the more painful since there are several exciting projects among the unclassified projects whose authors respected the stipulations of the program. The Central Society of Architecture of Belgium calls upon the members of the Council of the League of Nations to reconsider the final outcome of the competition."

"The Competition for Building a League of Nations Palace in Geneva, The Project of MM. Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer, General Considerations," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 7, July 1927, pp. 223-226.

Editor Josef Gantner published Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer's League of Nations design in the July issue, which also contained a construction update on the German Werkbund's Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart. (See below.)

"For the Opening of the Great Werkbund Exhibition," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 7, July 1927, pp. XXXIV-XXXV.

Das Werk reported in July on the construction of the then-famous Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart. Little did Albert Frey know that his future Le Corbusier atelier-mate, Alfred Roth, was then in Stuttgart overseeing construction of Le Corbusier's two houses seen in the background of the upper left photograph, as well as compiling a book documenting the project. Le Corbusier had entrusted Roth to oversee the project while he was busy conducting an all-out publicity campaign to be awarded the commission for the Palace of the League of Nations in Geneva. Frey was also in the dark regarding Alfred Roth's role on Le Corbusier's League of Nations design team and was likely impressed with Neutra and Schindler's proposal since he, by then, had certainly seen examples of their work in

Das Werk and

Wie Baut Amerika?.

Frey was likely intrigued with the August issue of Das Werk, since it contained an analysis of the League of Nations design competition and a brief discussion of two more of the projects by Scheibler-Schnabel and August Perret. Editor Josef Gantner opined:

"Das Werk ... published the Le Corbusier project in its June issue, the Neutra (together with R. M. Schindler) project in its May issue, and the Meyer-Wittwer project in its July issue, thus drawing attention to three of the most interesting and best works ever. ... Public opinion in the Germanic countries has so overwhelmingly favored Le Corbusier's ingenious solution that even the political authorities in Geneva can no longer ignore this project, which as rightly been described as by far the best of all." ("The League of Nations Competition," Josef Gantner, Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 8, August 1927, pp. 254-256. Author''s note: Although the Neutra-Schindler entry failed to win a prize, it was selected along with those of Le Corbusier and Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer of Basel for display at the German Werkbund "Die Wohnung" ehibition in Stuttgart in conjunction with the Weissenhof housing exhibition and then traveling to orther major European ceenters. (Hines, p. 72)

"Die Wohnungsausstelung Stuttgart 1927, De Beiden Hauser Le Corbusier und Pierre Jeanerret," Das Werk, Vol. XIV, No. 9, September 1927, pp. 260-278.

The September 1927 issue of Das Werk contained a 19-page article on the Weissenhof, about four pages of which were focused on the former Swiss architect, Le Corbusier. Another five pages were committed to the ongoing controversy over the League of Nations design competition. The issue also announced the publication of Zwei Wohnhauser von Le Corbusier und Pierre Jeanneret by Alfred Roth by the Akademischer Verlag in Stuttgart. (Ibid., p. XXXIII).

Left: Bau und Wohnung, Forward by Mies van der Rohe and designed by Willi Baumeister, Deutschen Werkbund, Verlag Wedikind, Stuttgart, 1927. Right: "Sonderausgabe Baukunst und Bauhanwerk," Model and plan of the layout of the Weissenhofsiedlung showing the architects taking part, Stuttgart, July 23, 1927.

The German Werkbund published a book on Weissenhof in conjunction with the exposition which included a preface by Mies van der Rohe and contributions by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret (Five Points for a New Architecture), Victor Bourgeois (Remember the Limits!), Walter Gropius (Ways to Factory Made House Production), J. J. P. Oud (Explanatory Report) and many others. Richard Neutra managed to get an ad for his book Wie Baut Amerika? Placed on the same page, adjacent to the model and plan of Weissenhof. On May 31, 1927, Neutra, Knud Lonberg-Holm, and Frederick Kiesler were also asked by the exhibition subcommittee to gather American material for the exhibition. (From Wolkenbugel: El Lissitsky as Architect, Richard Anderson, MIT Press, 2024, p. 311).

All the architects participating in Die Wohnung exhibition were listed, and their work was itemized in the catalog for the Die Wohnung Exhibition, which also included a Plan- und Modellausstellung [exhibit of plans and models] held in conjunction with Weissenhof. Le Corbusier was most mentioned, with over 40 items listed in addition to his two houses at Weissenhof. Gropius had 35 items in the exhibition in addition to his Weissenhof work. Mies van der Rohe was next with over 10 items, plus his apartment building at Weissenhof and the furniture stand at Die Wohnung, shared with Lily Reich. Neutra had seven items listed, including three for his League of Nations Palace, which was exhibited alongside the Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret and Hannes Meyer & Hans Wittwer entries. Albert Frey's colleagues from Brussels, Victor Bourgeois and J. J. Eggericx, were also represented. Bourgeois's Weissenhoff house also included artwork by his 7 Arts colleagues Oscar Jespers, Pierre Floquet, Karl Maes, and Willy Baumeister. Frank Lloyd Wright had four items that were not mentioned in Langmead. The exhibition would travel widely across Europe for the following two years, beginning in Basel and Zurich, Switzerland, in March and April 1928, where it was almost certainly viewed by Albert Frey before he traveled to Paris. (See more on this later below.)

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeaneret, L'Architecture Vivante, Première Série, edited by Jean Badovici, Morance Editions, Paris, 1927. (In Le Corbusier et Livre, Exhibition of Le Corbusier's first edition books, COAC, Barcelona, 2005, p. 107).

In late 1927,

L'Architecture Vivante also combined the fall and winter editions into a single extract, which again included the Palace of the Society of the League of Nations in Geneva, Pavilion de l'Esprit Nouveau in Paris, Villa Stein in Garches, Villa La Roche, and Pessac in Bordeaux, among other Le Corbusier projects. Albert Frey was very likely to have seen this in Le Corbusier's atelier after he arrived.

Das Bauhaus in Dessau und Seine Arbeiten, by Will Grohmann, Das Werk, Vol. 14, No. 1, January 1928, pp. 4-13.

Das Werk's January 1928 issue contained a 10-page article, "The Bauhaus in Dessau and Its Works," which included buildings designed by Walter Gropius and furniture designed by Gropius and Marcel Breuer with photos by Lucy Moholy-Nagy. This article would have been of great interest to Frey. The same issue also included an article on the German Werkbund "Neues Bauen" exhibition in Basel, which Frey was almost certain to have taken in.

Left: "Vom Neuen Bauen, Industrialisierung des Bauens" by Hans Schmidt, Das Werk, Vol. 14, No. 1 January 1928, pp. 34-37.

The same issue contained a four-page article, "On New Building, Industrialization of Construction" by Hans Schmidt, which was essentially a preview of the traveling German Werkbund plans and models architecture show from the Die Wohnung exhibition from Stuttgart, which was set to open at the Basel Gewerbemuseum in January and the Zurich Academy in March. All the illustrations in Schmidt's article also appeared in the Basel exhibition catalog, also authored by Schmidt.

Left: Exhibition poster for Neues Bauen Wanderaustellung des Deutschen Werkbundes, Kunstgewerbe Museum, Zurich, January 8 to February 1, 1928. Right: Ibid., Gewerbe Museum Basel, February 12 to March 11, 1928. Poster design by Theo H. Ballmer. From MoMA. Left: Exhibition catalog for Neues Bauen Wanderaustellung des Deutschen Werkbundes, by Hans Schmidt, Gewerbemuseum Basel, February 12 to March 11, 1928. Center and right: Directory of Architects, Ibid., pp. 19-20.

Left: Neues Bauen Wanderaustellung des Deutschen Werkbundes, installation view of "Utiltarian Buildings," Museum of Applied Arts, Zurich, 1928. Right: Ibid., Weissenhofseidlung, Stuttgart. (Richardson, pp. 334-5).

Albert Frey almost certainly viewed the traveling German Werkbund exhibition in nearby Zurich in January, since that was where he was then living and working. Architects listed in the exhibition catalog included Frey's recent employer, J. J. Eggericx, and Victor Bourgeois, as well as his future employer, Le Corbusier. As in Stuttgart, Richard Neutra was also featured in the show with a few projects, including his and still uncredited R. M. Schindler's League of Nations design competition entry displayed alongside the entries of his soon-to-be employers Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret, and Hannes Meyer & Hans Wittwer, perhaps through the largesse of Swiss architect Werner Moser, his Taliesin colleague from 1924 and also listed in the catalog.

The "New Building" exhibition, a traveling showcase of the German Werkbund, was a significant event in 1928. It focused on promoting modern architectural styles and designs, particularly those associated with the Werkbund's vision for a new, functional, and aesthetically pleasing built environment. The exhibition aimed to educate the public about these new approaches and their potential for shaping a modern society. After Basel, the show traveled to Stettin (Szczecin), Vienna, Prague, Breslau (Wroclaw), Amsterdam, Hannover, Kiel, Aachen, Dortmund, and Graz. (Richardson, p. 316).

Left: Catalog for "The New Home" exhibition at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Zurich, June 16-July 1928. Cover design by Ernest Heller. From Wiedler.ch Right: "Announcement of the Exhibition 'The New Home' Zurich," Das Werk, June 1928, p. 171.

Frey most likely attended "The New Home Exhibition" at the Zurich Museum of Decorative Arts during the summer in Zurich before leaving on his Paris adventure. The show was created by Max Ernst Häfeli and emerged from a competition organized by the Zurich Museum of Decorative Arts and financed by the city. Haefeli also attended the inaugural CIAM conference with Le Corbusier at Madame Helene de Mandrot's Castle La Sarraz, a three-hour train ride from Zurich, in late June.

Left: Exhibition poster for the Schweizerische Stadtebau-Ausstellung exhibition at the Zurich Kunsthaus, August 4-September 2, 1928. Poster design by Allison Hale. Right: "Die Schweizerische Stadtebauausstellung 1928," Das Werk, July 1928, pp. 193-6.

The Swiss Federation of Architects was also celebrating its 20th anniversary in 1928 with an exhibition at the Zurich Kunst Haus. Along with its general meeting on August 4 and 5, it is opening the Swiss Town Planning Exhibition, which it has organized with the cooperation of the cities of Basel, Berne, Geneva, Laussane, St. Gallen, Biel, and Le Corbusier's hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Left: Exhibition poster for the Schweizerische Stadtebau-Ausstellung exhibition at the Zurich Kunsthaus, August 4-September 2, 1928. Poster design by Allison Hale. Right: Zurich Kunsthaus, ca. 1935 from Wikipedia.

Frey likely also would have been in attendance at the August Swiss Town Planning exhibition at the Zurich Kunsthaus, as he was preparing himself to make the leap to Paris with high hopes of apprenticing with Le Corbusier.

The first of over thirty letters of correspondence between Siedfried Giedion and Le Corbusier regarding the planning of the inaugural meeting of CIAM took place when Giedion wrote to Le Corbusier in March 1928 with great concerns over who would eventually show up in La Sarraz.

"As for the congress, I am skeptical. Madame de Mandrot came to us when everything was set! It's too late. - Architecture is not a social toy! Moser returned from Germany yesterday. We will speak with her and send you the program of the Dutch and the Swiss. There is a possible danger that both countries will not come. Naturally, the Dudocks [sic], Mallet-Stevens, etc., come, but it is necessary that the young people do not abstain, nor the Swiss, nor the May and Stams, etc. Without that? Madame de Mandrot writes that she receives acclamations from all countries, but WHO comes, who really comes, the NAMES, that is, the level of the congress. Do you know precisely WHO WANTS TO COME?" ("Un Verano de 1928," Guillemette Morel Journel, LC. Revue de Recherches sur Le Corbusier, No. 6, pp. 72-90).

Villa La Roche picture gallery interior design by Charlotte Perriand with assistance from Alfred Roth, 1928. (Barsac, pp. 110-111).

In the meantime, the Villa La Roche picture gallery badly needed an interior redesign after it suffered the explosion of two radiators in the winter of 1927. This was Charlotte Perriand's moment to shine with her first Le Corbusier assignment, and she answered with one of her creative interiors, thoughtfully redesigning the room with assistance from Alfred Roth to embellish its warmth with her new furniture and also improve its lighting fixtures. The above picture was staged for publicity purposes; all the furniture pieces - Fauteuil grand comfort, Chaise lounge basculante, and Fauteuil dossier basculant - were carefully arranged around the table manifeste and photographed. (FLC and Barsc, p. 110).

Left: Villa Church guest house dining room, 1928, Charlotte Perriand, designer. (Barsac, p. 114). Right: Villa Church music pavilion, 1928, Charlotte Perriand, designer. Photograph by G. Thiriet. (Barsac, p. 117).

Perriand had so much success with the Villa La Roche that Le Corbusier confidently turned her loose on the Villa Church, where she spent much of the rest of 1928 duplicating her stellar efforts. Villa Church was a compound of three buildings: the guest house (Pavilion A), the library-music room (Pavilion B), and the residence for the Church couple (Pavilion C). She worked mainly on the interior design of the guest house and the music room with Alfred Roth. Albert Frey had some minor involvement after he joined the atelier in October.

Diagram on Alfred Roth's lecture on Le Corbusier, April 10, 1928. (Roth, p. 50).

After Weissenhof, Roth returned to Le Corbusier's atelier in November 1927 and began working on Villa Stein in Garches and Villa Church in Ville d'Avray, soon to be joined by Charlotte Perriand. In mid-January 1928, he was invited by the avant-garde Dutch group of architects to lecture on his mentor Le Corbusier. The date of April 10th was chosen, and Roth started carefully planning his lecture. He recalled Gerritt Reitveld, Jan Duiker, Cornelis van Eesteren, and many other notable Dutch architects being in attendance. (Roth, p. 50).

Immeuble Wanner, Geneva, 1928. FLC.

Alfred Roth also reminisced about working on what would in 1930 become the Immeuble Clarte in Geneva, but began as a study for the Wanner Building in 1928. Project 'Mundaneum', Geneva, 1928. (Roth, p. 47).

In early 1928, Roth also worked on the Mundaneum, of which he recalled: