Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

This biographical profile of avant-garde dancer Bertha Wardell (see above), who performed her "Dances in Silence" at the Schindler's Kings Road house (see announcement below for example), the California Art Club at Aline Barnsdall's Hollyhock House on Olive Hill, and Edward Weston's Carmel studio evolved while researching a book in progress with the working title "The Schindlers and the Westons: An Avant-Garde Friendship." In this essay I hope to shed new light on just one of dozens of similar mutual friendships the Schindlers and Westons accumulated over the years through their social interactions at Kings Road, Weston's studios, and mutual friends' salon gatherings, lectures, concerts, recitals, exhibition openings, and theatrical and dance performances in both Los Angeles and Carmel. Edward and son Brett photographed many of these same friends whom Pauline Schindler also wrote about in the pages of The Carmelite which she published and edited in the late 1920s and Edward wrote about in his Daybooks. Heretofore completely unrecognized for her important role in the evolution of modern dance and dance education in Los Angeles, Bertha Wardell is one of the more interesting characters to arise from the bohemian, avant-garde milieu of 1920s-1940s Los Angeles and Carmel.

Announcement for Bertha Wardell performance of "Dances in Silence," March 16, [1929] at Kings Road. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, R. M. Schindler Collection.

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

"Dances in Silence," Bertha Wardell. Photographer uncredited (Attributed by me to Edward Weston). From The Carmelite, October 16, 1929, p. 1. From Harrison Memorial Library, Carmel.

With all of the interaction between Weston and his dance subject circles, it seems incomprehensible that he and Wardell did not meet until 1922 as she later recollected (see letter below). If that was indeed the case, they might possibly have met at the Schindler's recently completed Kings Road house in what is now West Hollywood. Pauline Schindler's sister Dorothy Gibling, then also living at Kings Road, joined Wardell on the UC Southern Branch Physical-Education Department faculty in 1922.

Wardell's below 1950 letter responding to Weston's request to selected former lovers seeking biographical memories as he became more serious about chronicling his life also inaccurately dated their 1927 reunion upon his return from Mexico.

Wardell's below 1950 letter responding to Weston's request to selected former lovers seeking biographical memories as he became more serious about chronicling his life also inaccurately dated their 1927 reunion upon his return from Mexico.

"My dear Edward: -Your letter was like the embodiment of a thought. I had had a letter in mind to you ever since reading the article about you in American Photography last summer. I was delighted that you were given your due as the greatest of living photographers... ... I am, of course, flattered that anything I might have said about your work still is important. Your success has always been to me your gift of selecting exactly the right way of dealing with your subject. ... ... We met sometime in 1922. The fall of that year, I believe. It was then that you did the portraits of me ... Then the next contact was when you returned from Mexico in 1928-29. In a curious way I am reminded of your work when I look at a fine Chinese blue and white vase that I enjoy every day. The Chinese artists drew their power from the long contemplation of objects until they had penetrated and had been penetrated by the reality of them. You achieve the same powerful effect by the choice of a detail which represents the particular whole, and, what's more, all related whole ... ... The warmest affection goes to you, Edward, and the affectionate remembrance of things past. Love - Bertha" (From Edward Weston: His Life by Ben Maddow, Aperture, 2000, p. 236).

(Author's note: Bertha's Freudian reference to the word "penetrated" echoed her similar use of the term in her 1925 essay on her creative process in Mary Austin's Everyman's Genius excerpted later below).

"L.A. Artist Cupid to Dancing Shawns," Los Angeles Herald, November 28, 1914, p. 1. Clipping from the Ramiel McGehee Ruth St. Denis Collection, UC-Irvine.

While a student at the State Normal School until her 1917 graduation, Bertha was apprenticing with the Norma Gould Dance Company with which she would remain associated as a teacher and performer throughout the early 1920s. The above late 1914 Los Angeles Herald article listed Wardell and her future business partner and lover Dorothy Lyndall as performers in a welcome home dance fest presented by Gould for her former dance and business partner Ted Shawn and his new wife, the renowned Ruth St. Denis. Likely through his by then lover Margrethe Mather's movie studio connections, this was about the time that Weston began his interest in photographing the dance, with St. Denis and Shawn being two of his earliest dance subjects. (See Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011, pp. 78-9).

"Dance to be Given by City Mothers," LAH, February 18, 1915, p. II-1).

Gould's star pupils, the blossoming Wardell and her intimate friend Dorothy Lyndall, must have been thrilled to be featured on the cover of of the second section of the Herald a few months later.

"Two pretty Los Angeles girls, dressed as Grecian nymphs, have been invited by the City Mothers to give exhibitions of true aesthetic dancing, with all its beauty and grace. They are Dorothy Lyndall and Bertha Wardell, accomplished pupils of Norma Gould. Miss Lyndall, in a soft gown of dull red, with bunches of grapes festooning it and a grape wreath in her flowing golden hair, will dance “The Bacchante.” Miss Wardell will dance “Thistledown” in a costume of pink, bedecked with dainty flowers. Numerous young peoples' organizations will be present at the municipal dance tonight." (Ibid).

"Physical Education Club," The Exponent, State Normal School Yearbook, 1917, p. 81.

Wardell was an active and esteemed student in the the State Normal School Physical Education Department majoring in dance. During her senior year she was listed as "The good spirit of the department" and was elected founding president of the Physical Education Club (see above). One of the Club's faculty advisors was the popular and multi-talented Glenn Sooy who also performed in the Student Body Vaudeville show and coached the football, basketball, baseball and tennis teams. Sooy would soon marry Louise Pinkney who was a Fine Arts Department faculty member who also sang in the Girl's Glee Club and performed alongside Glenn in the Vaudeville show. She later became head of the Fine Arts Department and worked with later Schindler-Weston circle intimates, 1917 graduate Annita Delano and 1925 graduate Barbara Morgan nee Johnson. (For much more on the Delano-Morgan friendship see my "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad").

Wardell almost certainly viewed, and was inspired by, an October 1915 exhibition of 42 of Weston's photographs in the State Normal School's beautiful new gallery featuring many well-known dancers. In a rave review of the show, Los Angeles Times art critic Antony Anderson particularly singled out Weston's images of Maud Allan, Ruth St. Denis, and Wardell's teacher Norma Gould's former partner Ted Shawn, for whom she had recently performed (see below).

Anderson, Antony, "Art and Artists: Artistic Photographs," Los Angeles Times, October 31, 1915, p. III-21.

Teaching out of her home since 1908, Gould had formed her own Los Angeles dance company under the management of impresario Lyndon E. Behymer the following year. Coincidentally, Shawn (see below) moved to Los Angeles in 1912 and also established a school and small performing company. The following year he joined forces with his new dancing partner Norma Gould and began performing at such venues as the Ebell Club and appearing in the local press. ("Descriptive Dances Given at Ebell Club," LAH, October 13, 1913, p. 3).

"Tango and Waltz Steps Blended by Angeleno Dancers," LAH, December 11, 1913, p. II-1.

Also in 1913 the duo starred in an early two-reeler, "Dances of the Ages" under Shawn's direction. Gould and Shawn were also giving exhibition dances of the tango at the Hotel Angelus South American Tango Tea Room. In early 1914 they embarked with their small company of Interpretive Dancers upon a cross-country tour for the Santa Fe Railroad, reaching New York in March of 1914 after nineteen performances. ("Tangoers Go East," LAH, January 9, 1914, p. 19).

Norm Gould and Ted Shawn, 1913. From New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

While in New York, at 23-year-old Shawn's eager insistence, Gould introduced him to the 35-year-old Ruth St. Denis. He had first seen his early inspiration perform in his hometown of Denver in 1911 and fantasized about being her partner ever since. ("Guide to the Ted Shawn Letters to Barton Mumaw, 1940-1971"). During their first meeting they discussed their artistic ideas and ambitions and Shawn returned the next day to audition. He was immediately hired by Ruth's brother and manager to become her partner. On April 13, 1914, the new partners, with Gould in tow as part of the reconstituted company, began a lengthy tour of the southern United States. The jilted Gould soon "became ill" and returned to Los Angeles. In August of the same year the possibly then bi-sexual Shawn and St. Denis were secretly married (see below).

"Ruth St. Denis and 'Ted' Shawn Wed Secretly," unidentified publication, circa mid-1914. From the Ramiel McGehee Ruth St. Denis Collection, UC-Irvine.

A hint of jealousy is evident in Norma Gould's comments in the earlier above article as she wistfully lamented,

"Teddy Shawn was very ambitious and expected to work up in the company. But I guess he's just as much surprised as any of us to work up to being the manager of the 'boss' so speedily. They must just have danced their way into each others' hearts I think." ("L.A. Artist Cupid to Dancing Shawns," Los Angeles Herald, November 28, 1914, p. 1).

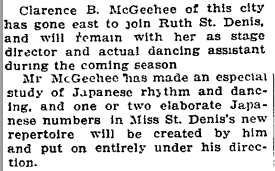

About two years before Norma Gould and Ted Shawn formed their 1913 partnership, future intimate in the Margrethe Mather, Edward Weston, Betty Katz, and Schindler circles, Clarence B. "Ramiel" McGehee began his own valiant attempt to become St. Denis's husband and manager. Fascinated with all things Chinese and Japanese, the widely traveled dancer, writer, and editor McGehee had previously spent about a year and a half there in 1907-09 learning the languages and soaking up the culture. He even went so far as to train for seven months to become a Buddhist monk at the Hasedera monestery at Kamakura. (Carmel Pine Cone, July 19, 1929, pp. 10-11 and Olive Percival Diaries, Huntington Library).

Yone Noguchi, 1903. Photographer unknown. From Wikipedia.

While in Japan McGehee had become friendly with the likes of artist Isamu Noguchi's poet father Yone Noguchi (see above) and was the English tutor for the future Emperor Hirohito. The below manuscript for Yone Noguchi's poem "Moon Night" along with a letter and a photograph, were found folded into a book owned by Ramiel, American Diary of a Japanese Girl by Yone Noguchi (see two below) which he later donated to the Denison Library at Scripps College. The October 1908 date at the bottom of the manuscript coincides with the time period Ramiel was in Japan thus this appears to be clear and convincing evidence that McGehee did indeed befriend Noguchi while there. (Author's note: Isamu Noguchi would sit for a Weston portrait in 1935. For more details see my "Richard Neutra and the California Art Club").

Manuscript for "Moon Night," Yone Noguchi, October 1908. From Claremont Colleges Special Collections.

American Diary of a Japanese Girl by Yone Noguchi, Stokes edition, 1902. From Wikipedia.

McGehee also befriended and lived for a time with Koizumi Setsu (see below), the widow of Lafcadio Hearn, and her family. At the time of Hearn’s death in 1904,

his eldest son, Kazuo, was ten, his other sons Iwao and Kiyoshi were six and

four, and his daughter Suzuko was just one year old. Hearn always preferred to be photographed in right profile so that his damaged left eye could not be seen, a factoid which if known to McGehee, would have endeared him, as he had a glass left eye himself and preferred the same profile (see two below for example).

Lafcadio Hearn and his wife Koizumi Setsu. Photographer unknown. From Wikipedia.

"Blind," Ramiel McGehee, 1920. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Olive Percival, n.d., photographer unknown. From Olive Percivsl: Los Angeles Author and Bibliophile by Jane Apostal, Department of Special Collections, University Research Library, University of California Los Angeles, 1992, frontispiece.

Upon his return to America, McGehee was likely one of the more knowledgeable people on all things Japanese in Los Angeles and was eager to share and capitalize on his knowledge. The affable, self-deprecating McGehee had befriended fellow Los Angeles Times employee, art critic Antony Anderson, before leaving for Japan. Through Anderson he met kindred Japanophile, author and bibliophile Olive Percival (see above), a close friend of rare book dealer and a future client of Frank Lloyd Wright's named Alice Millard. Percival, whom Anderson and McGehee were both then unsuccessfully courting, characterized McGehee as "a young Times reporter with an interest in Oriental Art." (Olive Percival: Los Angeles Author and Bibliophile by Jane Apostol, UCLA, 1992, p. 10 and Olive Percival Diaries, Huntington Library).

Olive diarised of her relationship with the young McGehee before his October departure for Japan,

"August 23, 1907: Lunched with Ozmun Orniston McGehee today and heard all his wonderful plans. It seems quite a dream but will soon be tangible, as he sails for the Orient in October. Such a strange fate, such a nice, talented boy! Only twenty-five! We made a compact for a life-long literary friendship and he ordered the most expensive thing on the card to celebrate his release from “The Times” and his really brilliant prospects as dear Mrs. West’s adopted son! He hopes I can have my oriental trip while he is there but alas! It is wholly improbable.

September 16, 1907: Orniston McGehee is interested in my verse as well as in me and so at his request I am writing him a steamie dittie and putting in some of my unpublished jingles – unpublished and unread. I scribble in rhymes because I cannot always read (with my miserable eyes) Because I have no one to talk to. … Mr. [Antony] Anderson [Los Angeles Times art critic] (see below) is on the verge of proposing to me and so something so very unpleasant must “happen” to prevent. He recently asked Mr. McG. not to attach his affections to me, as he was “jealous.” But naturally he got an evasive reply. How strange and singularly horrid he seems to be, not as my friend merely but in the role of a friend for Mr. McG. It would all make a Fireside Companion novelette, although between the ages of the hero and the heroine there is a trifling difference in age – fifteen years! How fate does joke with some people! With me certainly!" (Olive Percival Diaries, Courtesy Huntington Library).

Antony Anderson, 1919. Edward Weston photograph. From De Rome, A. T., "A Few Pictures Reviewed: Illustrations from California Liberty Fair Exhibition," Camera Craft, March 1919, p. 89.

Olive entered two mentions of McGehee while he was in Japan,

"N.d., ca. 1908: Mr. McGehee assures me that he loves me and my ways more and more every day! That he will think of me every minute in Japan and never cease to regret I am not with him! How much I love his ardent speeches! (Not him!)

N.d., ca. 1908: Mrs. West left Monday for Japan. Yesterday a thick packet of post-cards and photographs came from Mr. McG. He has been ill." (Olive Percival Diaries, Courtesy Huntington Library. Author's note: Mrs. West was off to visit McGehee whose trip she most likely financed.).

Likely strapped for funds, Ramiel would have welcomed his patroness Mrs. West with open arms. He escorted her on a grand tour during which he developed a passion for Zen Buddhism. Later in his sojourn he spent seven months studying in a Buddhist monestary. While McGehee was in Japan Olive exhibited some of her Japanese prints at the Ruskin Art Club in the Blanchard Building. The Herald reported,

"The exhibit this spring is a departure from the tradition of the club, and is confined to the graphic arts. The first room is given up to Japanese prints, and the four walls are thickly hung with the finest collection that has ever been seen in Los Angeles. ... The club is exhibiting the first large collection of Japanese prints ever shown in Los Angeles." ("Artists Gather to View Fine Exhibit," Los Angeles Herald, April 6, 1908, p. 9).Upon McGehee's return Olive recorded,

"May 17, 1909: Mr. McGehee is back from a year and a half in Japan. He, to my surprise, kissed me breathless - such is his pleasure to get back to a middle-aged person who "understands." He lived seven months in a Buddhist temple. Climbing Fuji, he put a pebble for me in each shrine, etc., etc.

May 22, 1909: Mr. McGehee came in with a lot of presents for me from Japan! He wishes me to tell no one, as he could remember no one else except Mr. Anderson, - the “Times” art “critic” who extorts sketches from all the poor artists in the city for a mere mention. (Lillie Drain says all the artists despise him – small wonder!) He is meddling with Mr. McGehee’s friendship and mine.

July 14, 1909: Mr. McGehee’s Sada Yacco interview is in the morning Times. Poor boy! Nice boy! (Author's note: Almost a full-page article, "Nippon's Star is Sada Yacco" by C. B. McGehee appeared on p. II-3 of the June 3, 1909 issue of the Los Angeles Times). We are to spend the weekend with Mrs. B. at Long Beach, in her charming cottage talking Japan continuously! I must be careful. I think he is intending to marry me. He says I am the one person in all the world who “understands,” that we must live in Japan, etc. ... We are congenial enough but oh! The impossibility of it all. I must be dull and unsympathetic by intent for I wish to save him heartaches. He declares he has already lived through too much, due to poor Mrs. West’s opposition to me. She need have no fears. And he no hope! … His good mother is very hard with him, about money and, about us! She need not worry. I’d not marry the child under any combination of circumstances (15 years my junior the least of the drawbacks) and, I’m convincing him as gently as possible.

July 24, 1909: Such perfect morning – sun, mist and cool breezes! Am having C. B. M. out for all day tomorrow to talk Japan and, Japanese Arts! (Olive Percival Diaries, Courtesy Huntington Library).

Being on the Times staff as it were and having a lifelong passion for the dance, McGehee was likely the unidentified "artist" recently back from a lengthy stay in Japan who accompanied dance critic Grace Kingsley to her interview of Ruth St. Denis during her April 24-30, 1911 triumphant Mason Opera House tour stop. (Author's note: Sixteen year-old Martha Graham also viewed one of these St. Denis performances which she credited with inspiring her dance career.).

McGehee couldn't help but see all the pre-performance buildup and glowing reviews in the local press and with his connections at the Times likely helped arrange the Kingsley interview. Prompted by questions from the "artist," St. Denis waxed poetic about adding Japanese routines to her repertoire. They also discussed the famous Japanese performer Sada Yacco. (Kingsley, Grace, "Kitchen Sink Was Throne; How Ruth St. Denis Learned Her Art," L.A. Times, April 27, 1911, p. III-4).

Indeed, St. Denis soon tapped Japanophile McGehee to assist her in Japanese routine development. Olive Percival chronicled McGehee's fascination with St. Denis in her diary, "Mr. McGehee is “rushing” Ruth St. Denis the dancer, this week. I wonder who could do him justice? Nobody of course but Leonard Merrick." (Olive Percival Diaries, April 26, 1911, Courtesy Huntington Library).

Olive Percival Residence aka "Down-hyl Claim," 522 San Pascual Ave., Highland Park, ca. 1906. Photo from The Children's Garden Book.

By now realizing that his earlier desires to marry Percival would not be realized, McGehee lost no time in ingratiating St. Denis with the proposal to assist her in the development of some Japanese routines as evidenced in Percival's later diary entries (see below). McGehee likely wanted to solidify his standing with St. Denis by sharing with her his kindred and deep Japanophilic connection with Olive.

"June 30, 1911: I haven’t succeeded in “losing” Mr. McGehee after all! He came in this afternoon to ask to bring Ruth St. Denis out to the house, and to tell me of his wonderful prospects. He leaves with her on Monday for the New York engagements where his playlet “The Sake Cups” is to be put on. Then for England and, Europe and, Asia – a whole year away!

July 1, 1911: I plan a good rest tomorrow, although I fear Mr. McGehee intends bringing Ruth St. Denis out. The house is in perfect order and unless I fuss about in the garden I may read all day long. Is such a thing possible.

Percival placing a Japanese lantern in her garden, n.d., photographer unknown. From "The Worlds of Olive Percival" by Peggy Bark Bernal," Verso.

July 5, 1911: Ruth St. Denis came out Sunday evening. Very delightful, natural, sort of young woman of 33 with prematurely white hair. Blue eyes with long black lashes. She was in a very few clothes! All white. The most amazing loose-jointed creature (except various cats I’ve studied). Wholly fascinating to watch." (Olive Percival Diaries, Courtesy Huntington Library).

"Music and Stage," L.A. Times, July 13, 1911, p. II-5. See also Jones, Isabel Morse, "St. Denis Returns," Los Angeles Times, November 7, 1926, p. III-22 referencing McGehee's role in helping St. Denis master the Oriental Dance).

St. Denis's strong desire to add Japanese numbers to her stage shows created the perfect outlet for McGehee's passion, talents and knowledge. Later to become an intimate in the Margrethe Mather, Edward Weston, Betty Katz, and Schindler circles, McGehee, to what in retrospect must have been one of the highlights of his life, was hired as publicist, stage director and choreographer for St. Denis through most of 1911-12. He eagerly helped her to develop her elaborate Japanese routines such as Omika which met with such great success the rest of her career (see above). There was even mention of marriage between the gay Clarence and Ruth with the idea seemingly quashed by her family (see below). (Author's note: There is an extensive collection of press clippings from this period in the Ramiel McGehee Ruth St. Denis Collection at UC-Irvine).

"Ruth St. Denis Engaged?" unidentified publication, August 30, [1911]. From the Ramiel McGehee Ruth St. Denis Collection, UC-Irvine.

"Rehearsing New Dances," Toledo Blade, January 8, 1912. From New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Apparently McGehee and St. Denis made rapid progress on developing the new Japanese routines as announcements regarding the impending debut of her new dances were beginning to appear around the country the following January (see above for example). Her inaugural Japanese performance took place in March or April. McGehee's coaching and indoctrination of St. Denis in all things Japanese was very thorough indeed evidenced by his positioning her in costume at the below Japanese tea ceremony during their time together.

Ruth St. Denis and Ramiel McGehee at a Japanese tea ceremony (center), ca. 1912. Location and photographer unknown. From Claremont Colleges Digital Library. Gift of Ramiel McGehee.

It is not yet clear how long their relationship held together, but it was long enough for McGehee to share everything he knew about Japan, greatly facilitating the metamorphosis of St. Denis into the 'Fantasie Japonaise' whom Weston photographed upon her and Shawn's return to Los Angeles in 1915 and widely exhibited with such great success soon thereafter (see below). Ironically, it must have been shortly after the time that St. Denis and McGehee eventually parted ways that Shawn entered into the picture in New York in the spring of 1914 (see earlier discussion).

In her later unpublished autobiographical manuscript St. Denis acknowledged McGehee's assistance thusly,

"I...became almost as engrossed in Japan as I had India and Egypt. Japan represented a blossoming of all my deepest aesthetic sense....At this time I met a young man named Clarence McGhee [sic] who shone very brightly in my life because he had lived and studied in Japan. He guided many of my first wanderings in the maze of Japanese culture, and the idea of a dance-drama began to take shape." (Ruth St. Denis autobiographical typescript, p. 203. Courtesy Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA).

Ruth St. Denis in the Dance of the Flower Arrangement from Omika, 1913. Photograph by Arnold Genthe. From the New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

Arnold Genthe was possibly the first photographer to capture St. Denis's Japanese metamorphosis with photos like the above taken in 1913 which also later appeared in his 1916 Book of the Dance.

Martha Graham in her Denishawn debut as Priestess of Isis in A Dance Pageant of Greece, Egypt and India, 1916. From Martha Graham: A Dancer's Life by Russell Freedman, Clarion Books, 1998, p. 30.

"Dances to Feature May Day Fete in L.A.," LAH, April 27, 1915, p. 1.

"Dances to Feature May Day Fete in L.A.," LAH, April 27, 1915, p. 1.

St. Denis and Shawn founded the first Denishawn School of Dancing in Los Angeles in 1915 and soon counted among their disciples the likes of modern dance progenitor Martha Graham (see above and below for example) and film stars Louise Brooks, Mabel Normand, Myrna Loy and the Gish sisters. (From Dance Heritage Coalition and Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, p. 78).

Denishawn Dance Company on the beach, location unknown, 1922. Martha Graham, center and Louise Brooks, second from right. (From the Louise Brooks Society.)

This was the same year that R. M. Schindler made his first trip to the West Coast and Edward Weston was experiencing his "awakening." (For more on Schindler's first Western "exposure" see my "Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence"). In retrospect, Weston wrote of his meeting Margrethe Mather shortly before this, emerging from his Puritanical, naive beginnings, and falling under the influence of her and her coterie.

"With this background I was suddenly thrown into contact with a sophisticated group, - actually they were drawn to me through my photography which had gone steadily ahead, - was my development. They were well-read, worldly wise, clever in conversation, - could garnish with a smattering of French: they were parlor radicals, could sing I. W. W. songs, quote Emma Goldman on freelove: they drank, smoked, had affairs, - I had practically no experience with drinking and smoking, never a mistress before marriage, only adventures with two or three whores. I was dazzled - this was a new world - these people had something I wanted: actually they did open up new channels, started me thinking from many fresh angles, looking toward hitherto unconsidered horizons. But there had to be a personal house-cleaning afterwards, - for, not to expose my real self to these clever new friends, I had to pretend much, to become one of them, parrot their thoughts, ape their mannerisms. Then came the day of reckoning when I saw through my own pretence." (March 17, 1931, DBII, p. 209).

Weston, Edward, "Spanish Dance," Katharane Edson, 1916. Courtesy LACMA Weston Collection.

It was around this same time that Edward Weston became fascinated with photography of the dance through Margrethe Mather's movie industry connections. He was also undoubtedly inspired by former Carmel denizen Arnold Genthe's earlier widely-exhibited and published work compiled in his 1916 The Book of the Dance which included his 1913 St. Denis Japanese work. Besides dozens of images of Shawn and St. Denis and many of their students in costume, Weston photographed Norma Gould, Maud Allan, Violet Romer, Martha Graham and others and quickly received much acclaim publishing and exhibiting the results to a global audience. (For example see Warren, pp. 79, 90). This new found fascination with dance photography also manifested itself in his eager willingness to perform his self-choreographed dance routines in drag at private soirees and parties and on stage before large appreciative audiences evidenced by numerous Daybooks entries.

Ruth St. Denis, 1916. Edward Weston photograph. Publication unknown. From the Ramiel McGehee Ruth St. Denis Collection, UC-Irvine.

On October 8, 1915, about the time of his earlier mentioned State Normal School exhibition, Weston received a note from noted art critic and future mutual friend with the Schindlers, Sadakichi Hartmann, which read,

"My Dear Weston: You are surely one of the anointed. In a class by yourself. The Dolores, Ruth St. Denis, Fantasie Japonaise (see above), and the large head of Margrethe Mather are masterpieces.I will use the prints to good advantage and write you up as opportunity dictates. Sometimes it takes a long while. But don't lose patience. It seems that I have to get to Tropico one of these days to have myself counterfeited by you, my collection would be incomplete without it. Alas! I see you are married, as we all are. Good Luck!I am on my way to New York, so write in great haste. Nude excellent too. Always same address." (Maddow, p. 72).

Ruth St. Denis cover, The Theatre, May 1916.

After parting ways with St. Denis upon Ted Shawn's arrival on the scene, McGehee supported himself translating and lecturing on Chinese and Japanese topics and producing and performing Japanese dance routines before a wide range of organizations and women's clubs. For example in February 1914 he loaned many of his Japanese prints to the Redondo Public Library for a two week exhibition and lectured on same. In July he loaned his Japanese etchings to the same library for a June 6-20 exhibition. (News Notes of California Libraries, April 1914, p. 302 and July 1914, p. 529).

Los Angeles School of Art and Design, 602 S. Alvarado St., Burnheim and Bliesner, architects, 1904. From USC Digital Archive.

Another venue for McGehee's Japanese lectures was the Los Angeles School of Art and Design's Palette Club which likely included as members aspiring architects Lloyd Wright and Paul Williams who was enrolled in drawing classes at the School around this time. Founded in 1887, the School of Art and Design was located at 602 S. Alvarado St. overlooking Westlake Park (see above). The school's curriculum included courses in composition and perspective and mechanical and architectural drawing. Ramiel and Lloyd were also likely to have attended, and possibly even provided material for, the Palette Club's December 1914 meeting at which instructor Hamilton Wolf gave a lecture on Japanese art illustrated with prints and books from Japan. Like Lloyd's father, Ramiel, with financial support provided by his patroness and earlier-mentioned Japanese travel companion Mrs. West, avidly collected Japanese art and art books during his year and a half in the Orient. ("Anderson, Antony, "Art and Artists," Los Angeles Times, December 13, 1914, p. III-6.).

Lloyd Wright, ca. 1920. From "The Blessing and the

Curse" by Thomas S. Hines in Lloyd Wright: The Architecture of Frank

Lloyd Wright, Jr. edited by Alan Weintraub, Abrams, 1998, p. 14.

Wright (see above) lectured at the Palette Club the following April on "Architecture and Its Bearing on the Community." Lloyd was also at this time working with Irving Gill and Paul Thiene on landscape design projects and providing architectural renderings for numerous clients out of his office in the Mason Building. ("Anderson, Antony, "Art and Artists," Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1915, p. III-21 and "Art and Design," Los Angeles Times, July 9, 1915, p. I-9. For much more on Lloyd Wright's 1911-1914 apprenticeship with Irving Gill see my "Irving Gill and Homer Laughlin and the Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Los Angeles, Part II, 1911-1916").).

Installation photo of Exhibition of Japanese Colour Prints, Art Institute of Chicago, March 5 to March 25, 1908.

In January 1916 Los Angeles Museum of Science, History, and Art curator Everett Carroll Maxwell staged the exhibition "The N. J. Sargent Collection of Japanese Prints" which would have undoubtedly attracted Ramiel and Lloyd. Lloyd's father had by then amassed a formidable collection of Japanese prints during his 1905 vacation and 1913 trip to begin preliminary discussions on the commission for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He lent prints from his collection for exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1906 and 1908 (see above for example). (Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Japanese Colour Prints, March 5 to March 25, 1908).

The Japanese Print: An Interpretation by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ralph Fletcher Seymour, Chicago, 1912.

McGehee was also likely aware of the senior Wright's fascination with Japan, either through Lloyd and/or possibly through knowledge of Wright's Chicago exhibitions of his extensive print collection. More likely, Ramiel's Japaniana collecting, or his earlier friendship with Lloyd would have led him to FLW, Sr.'s book The Japanese Print published by the Schindler's close Chicago friend Ralph Fletcher Seymour (see above). (For more on Seymour, see my "R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra and Louis Sullivan's Kindergarten Chats," hereinafter simply "Chats" and "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924").

In February 1916 McGehee gave a talk on Japanese folklore before the Palette Club where he presented Japanese dances in costume and displayed an exhibition of Japanese prints with Lloyd likely in attendance. Later that year McGehee lectured on the Japanese Drama to the Channel Club at the Clark Hotel and again on Japanese folklore in costume to the Santa Monica Women's Club. ("Art Notes," Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1916, p. III-4, and "Society," Los Angeles Times, November 12, 1916, p. III-5. For much more on Lloyd Wright's period involvement in the local dramatic community see my "Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, R. M. Schindler, Anna Zacsek, Lloyd Wright, Reginald Pole, Beatrice Wood and Their Dramatic Circles" (WMSZ)).

Sometime in 1916 McGehee became involved with a Japanese theatrical troupe called the Cherry Blossom Players for which he directed drama and dance productions under his friend Norma Gould's manager and impresario Lyndon E. Behymer. It seems plausible that Gould's disciple Bertha Wardell and friends performed in some of the Cherry Blossom Players dance routines and/or his other earlier-mentioned local performances such as at the Palette Club.

In the "Players" debut performance at the Alexandria Hotel in January 1917, the stage was graced with sets designed by a then seasoned set designer Lloyd Wright who at the time was also designing movie sets for Paramount Pictures. Coincidentally, around this same time Lloyd was also completing his first ever architectural project, an artist studio and garage for the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and Palette Club director, Mrs. L. E. Garden-MacLeod. He had broken ground on the one-story, three-room, 34 x 40 ft. studio at 447 S. Occidental Blvd. the previous August. ("Studio and Garage," Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer, August 19, 1916, p. 17. Author's note: The builder for the MacLeod studio was C. D. Goldtwaite who likely through Lloyd's largess obtained the contract to construct Aline Barnsdall's Hollyhock House on Olive Hill in 1921. Goldthwaite had also been one of the builder's for the City of Torrance projects designed by Lloyd's then employer Irving Gill. Goldthwaite and Lloyd and his 1915-16 landscape design partner Paul Thiene all had offices in the recently completed Marsh-Strong Building at the southwest corner of 9th St.and Main St.).

While Lloyd was collaborating with Ramiel on the Cherry Blossom Players sets, his father had been in preliminary discussions with Aline Barnsdall regarding the plans for her Hollyhock House residential and theatrical compound before departing for Japan on December 28th to begin work on the Imperial Hotel. (For much more on Barnsdall's activities surrounding her Los Angeles Little Theatre in late 1916 and early 1917 and Lloyd's collateral involvement and marriage to Markham see my "WMSZ." For much more on Barnsdall and the Schindlers see my "Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism" hereinafter "Vagabond").

Clarence McGehee portrait with announcement of upcoming Cherry Blossom Players productions, Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1916, p. II-10.

The buzz surrounding the Barnsdall-Richard Ordynski productions at Barnsdall's Los Angeles Little Theatre starring Lloyd's new bride Kirah Markham, and Ramiel's contagious enthusiasm for the Cherry Blossom Players likely helped him convince impresario Behymer that being able to advertise set designs by the son of the noted architect Wright would help in attracting a wider audience (see article below for example). ("Events Briefly Told" Ordynski Will Lecture," Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1916, p. II-2 and "Women's Work, Women's Clubs," Los Angeles Times, November 24, 1916, p. II-3).

"Cherry Blossom Players to Give Performances Soon," Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1917, p. III-19.

The troupe traveled to Pasadena for performances at the venerable Huntington Hotel in February. ("Japanese dances to feature show: Seven interpretative numbers on the program of Cherry Blossom Players," Pasadena Star News, February 10, 1917).

Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1919, p. III-32.

Still organizing and collaborating with Cherry Blossom Players events such as the above 1919 fund raiser, McGehee performed on the same program for two weekend engagements at the Beaumont Woman's Club in early May. Also on the bill were Norma Gould (likely with Wardell and Dorothy Lyndall in accompaniment), Grace Vierson, longtime patron Katherine Fiske, and modernist pianist Ruth Deardorff Shaw (see below), whom the Schindlers later first heard perform with Edward Weston in the summer of 1922. (Warren, p. 253 and "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School.").

Ruth Deardorf-Shaw, 1922. Photo by Edward Weston. From Stephen Cohen Gallery.

As was the case virtually every summer, Norma Gould organized a series of two-week courses in outdoor mountain settings to attract new students to dancing careers. The below brochure announcing her ninth summer session was mailed to McGehee, begging the speculation as to his involvement as a teacher alongside Bertha Wardell and Dorothy Lyndall who were still working for and performing with Gould at the time.

Around this same time in 1919 McGehee became an intimate within the Mather-Weston-Katz orbit. Weston attended a dance performance by Clarence in early July and invited him and his friend to visit, perform and pose at his studio later that month (see below for example). (Edward Weston, letter to Clarence Blocker [Ramiel] McGehee, July 11, 1919, EW Archive. Cited in Warren, p. 160). (Author's note: It seems incomprehensible that McGehee did not become part of the Weston-Mather circle until mid-1919 as suggested by Warren. Lloyd Wright's 1915 residence at 618 W. 4th St. was a block away from Margrethe Mather's studio at 715 W. 4th St. and Ramiel and Lloyd's earlier-mentioned Palette Club activities also almost certainly indicates a crossing of their paths.).

Ramiel McGehee in Japanese Noh Dance, 1919. Edward Weston photograph. From Merle Armitage Dance Memoranda edited by Edwin Corle, Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946.

Betty Katz, Clarence [Ramiel] McGehee and unidentified man in Japanese-Style Garden, ca. 1919. Unidentified photographer. Collection of Martin Lessow. (From Warren, p. 162). (For more on Katz, see my "Betty Katz Kopelanoff Household Brandner: From Her Attic to Kings Road" ).

McGehee remained in the center of dancing and Japaniana circles evidenced by, for example, himself and Wardell's mentor Norma Gould performing at a tea with many others at the Fiske residence in Hollywood during September 1919 and the above image of himself and Betty Katz at a Japanese garden. ("Entertained for the Misses Fiske," Holly Leaves, September 6, 1919, p. 19)

In the meantime Norma Gould continued to feature her by then pet Wardell in the pages of the Los Angeles Herald. In her June 1916 production of the ballet "Jeanne d’Arc" at Frank Egan's Little Theatre she featured Wardell and Marjorie Capron (see below). (For much more on Egan's Little Theatre see my WMSZ).

Bertha Wardell, top righ and bottom left. "40 Pretty Dancers Will Aid Pageant," LAH, June 1, 1916, p. II-1.

Wardell graduated with a "general professional degree" in 1917 from the State Normal School. In 1919 the college became the University of California Southern Branch where she began teaching dance in the Physical Education Department the following year through the largess of her mentor and faculty member Norma Gould. (Author's note: Later Schindler and Weston social orbit habitues, Annita Delano and Barbara Morgan nee Johnson joined the faculty's Fine Art Department the school's inaugural year and 1925 respectively).

Bertha's courses included general physical education for sophomores, Folk Dancing and Aesthetic Dancing. By the 1922 school year she had become close friends with art teacher Annita Delano and art student Barbara Johnson who were both fascinated by modern dance. She was joined on the Physical Education faculty for the 1922-23 school year by Pauline Gibling Schindler's sister, Dorothy Gibling, who moved into Kings Road shortly after its 1922 completion (see far right below). Gymnastics teacher, Woman's Athletic Association faculty advisor and Woman's Basketball coach Dorothy remained on the staff through the 1923-24 year. Dorothy was credited in the school yearbook for the success of the woman's basketball team and its winning the conference title . ("Woman's Athletic Association: Basketball: Conference Champion Team," Southern Campus, 1924, p. 260. For more on Annita Delano, Barbara and Willard Morgan and Kings Road see my "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism" (hereinafter LAMod) and "Vagabond.").

R. M. and Pauline Gibling Schindler, Sophie and Edmund Gibling, Dorothy Gibling and Mark Schindler at Kings Road, summer 1923. (From "Life at Kings Road: As It Was 1920-1940" by Robert Sweeney, p. 93 in The Architecture of R. M. Schindler). (Schindler Family Collection, Courtesy Friends of the Schindler House.

Wardell's friend and faculty-mate Dorothy Gibling can be seen at the far right of the above Kings Road photo.

Thanksgiving at Kings Road, 1923. Clockwise from far left, Dorothy Gibling, Betty Katz, Alexander "Brandy" Brandner, obscured, Max Pons, Herman Sachs, Karl Howenstein, Edith Gutterson Howenstein, Anton Martin Feller, E. Clare Schooler, and unidentified. Photograph attributed to R. M. Schindler. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, R. M. Schindler Collection.

(Author's note: Dorothy can also be seen at the far left in the above 1923 Kings Road Thanksgiving picture seated next to former Weston lover and model Betty Katz who will be the subject of a future article. Continuing clockwise we have Betty's future husband, Alexander "Brandy" Brandner, obscured, Max Pons, Herman Sachs, Karl Howenstein, Edith Gutterson (erstwhile Chicago girlfriend of Schindler who married Howenstein in New York in 1921), Anton Martin Feller (then a Frank Lloyd Wright employee working on the Freeman and Storer Houses), Dorothy's lover E. Clare Schooler, and unidentified. Sachs, a soon-to-be Schindler client and collaborator, established the short-lived Chicago Industrial Arts School in 1920 at Jane Addam's Hull House, Pauline's earlier place of employment, and directed the Dayton Institute of Art in 1921-22 before moving to Los Angeles in 1923. Howenstein was also friends of the Schindlers in Chicago where he worked at the Art Institute of Chicago with Edith before moving to Los Angeles to become Director of the Otis Art Institute. Karl and Edith lived in the Kings Road guest apartment for two years during 1922-4). (For more on the Howensteins, Sachs and Brandner see my "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association").

Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, December 1921, front cover. (For more on Harriet Monroe's inaugural publisher Ralph Fletcher Seymour, see "Chats").

Wardell's December 1921 letter to the editor, Harriet Monroe, a frequent publisher of fellow poet, editor, and dramatist Alfred Kreymborg's work marked her encouragement for Monroe's apparent step towards a closer affiliation with poetry's allied arts including her passion, i.e., the dance.

"Dear Poetry,

To all serious students of the dance, the first sentence in your October article, "Poetry would like to celebrate its ninth birthday by inaugurating a closer affiliation with the allied arts of music and the drama - perhaps also the dance," is encouraging. That "perhaps" is deserved, only those who come in daily contact with the too-popular belief that the door to real achievement may be kicked open by a perfectly pointed toe can realize how far the dance has traveled from its dignified origin. In alliance with that music and poetry to which the dance really gave birth lies her only hope. Music and poetry give the dancer a reason for existence.We had the pleasure of working with Alfred Kreymborg in the summer of 1920 (see discussion below), and not only felt that we, as dancers, had profited, but we gained an insight into, and a feeling for, the rhytnm of modern poetry that nothing but the actual bodily expression of it could have given us. We have been fortunate also in being associated with a musician [Henry Cowell] who has used pieces of Sara Teasdale's, Vachel Lindsay's, Bliss Carman's, and other moderns, as themes for dance-music.Certainly poets, musicians and dancers need not fear to join forces. They have the fundamentals in common with such different, yet harmonious, outward manifestations of those fundamentals, surely the result will not be unworthy of poetry or music, and will surely be of infinite value to the dance in its reinstatement among the arts. We so often fail to say the pleasant things we think. Poetry is a monthly refreshment. It is like a breath from freshly opened flowers, or a drink of mountain water.

Bertha WardellLos Angeles, Cal." (For much more on Henry Cowell and his Schindler-Weston connections see my "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage").

During his extended 1920 lecture tour in California referred to by Wardell, poet Alfred Kreymborg called on Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn to try to interest them in his ideas of dancing to poetry. After chanting and playing for them while demonstrating with marionettes, Ruth and Ted immediately became so fascinated that they engaged the Kreymborgs to collaborate on a performance with their troupe. He related in his autobiography,

"[I] was engaged to undertake a bill of dances and pantomimes with some of the members, under the direction of Ted Shawn. So remarkably sensitive were these young girls to the slightest aesthetic design and so thoroughly trained in the traditions of interpretative dancing, that Ted Shawn only had to attend an occasional rehearsal. In order to disclose a variety of dramatic dynamics, [I] added the static play, Manikin and Minikin, and the puppets, playing from the hands of Dorothy [Kreymborg]. Rehearsals proceeded daily for five or six weeks, and along with the earth and the flower, the owls and the daisies that [I] had introduced at Madison, a bird, a tree and a stream, a willow, a sprite and a shadow, a juggler of balloons and stars and other dancing things were incorporated." (Troubadour: An Autobiography by Alfred Kreymborg, pp. 354-5).

The juggler of balloons Kreymborg included in the Denishawn collaboration indicates that Weston had most likely been in attendance during the Denishawn-Kreymborg rehearsals and/or performance evidenced by his portrayal of the troubadour and his mandolute serenading a rising flock of balloons (see below).

Alfred Kreymborg - Poet, August 3, 1920. (Warren p. 192 and note 53, p. 322). Edward Weston photograph. From Weston's Westons: Portraits and Nudes by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1989, p. 123. Also titled "Balloon Fantasy" by Weston in American Photography, October, 1921, p. 547 as cited in Warren, note 55, p. 322).

"Alfred Kreymborg," Holly Leaves, July 31, 1920, p. 1.

Shortly after his work with Denishawn, Norma Gould also requested that Kreymborg collaborate with her "more experienced" dancers, Bertha Wardell, Dorothy Lyndall and Elizabeth Schreiber (see above). (See also Kreymborg, p. 355). Their July 29th performance at the Hollywood Woman's Club was most likely attended by Gould colleague Clarence "Ramiel" McGehee and by Weston who met McGehee and Wardell around this time. ("Kreymborg Coming," Holly Leaves, July 24, 1920, p. 18).

Weston evidently liked what he saw from Norma Gould and her staff as he wrote to Betty Katz shortly thereafter, "Chandler has started private lessons with Norma Gould - more trading - pictures for dancing." (Edward Weston, letter to Betty Katz, n.d., ca. 1920-1. Center for Creative Photography).

Norma Gould posing in front of a Douglas Donaldson charger in Edward Weston's studio, ca. 1920-1. From Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra Program, April 1921. Courtesy Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives, Hall of Records. (For much more on Donaldson see my "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association" (SHAA)).

Kreymborg's Marionette, 1920. Margrethe Mather photograph. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2005.27.4261. (From Warren, p. 193).

Weston's companion, Margrethe Mather, who had previously photographed Kreymborg during his earlier 1917 lecture tour, also captured his dancing marionette (see above) close to the same time as Weston's studio balloon image. Kreymborg likely met Mather through their mutual friend, poet and artist William Saphier, who captured Mather's essence in "Margrethe" penned shortly after their 1916 tryst which Kreymborg later anthologized in "Others for 1919." Saphier helped Kreymborg edit his poetry journal Others, kept alive with the patronage of future Weston and Schindler circle member Walter Arensberg, and created the cover art for his autobiography (see below).

Troubadour: An Autobiography by Alfred Kreymborg, Boni & and Liveright, 1925. Cover art by Saphier.

Others, January 1919, cover art by Marguerite Zorach. From Modernist Journals Project.

In 1920 Wardell performed in UC Southern Branch's Director of Pageantry Norma Gould's production "Dionysia." She also danced with Gould's troupe in the Community Thanksgiving Pageant at the Theater Arts Alliance Amphitheater in Hollywood, soon to be the site of the Hollywood Bowl. The pageant was directed by future Schindler circle regular Hedwiga Reicher under the auspices of the Hollywood Woman's Club. (For more on Reicher's scandalous removal as director of the Thanksgiving Pageant see my SHAA).

"The Andalusia," Southern Branch Yearbook, 1921, p. 44.

Gould and Wardell again produced the annual Southern Branch dance pageant "The Andalusia" the following year (see above). The program theme was the celebration of the marriage of Ferdinand Magellan before his global circumnavigation. About 150 dancers took part in ensemble, group and solo dances accompanied by the University orchestra.

"University Fete," Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1922, p. X-7.

Wardell also helped produce Gould's annual UC Southern Branch spring production "Children of the Sun" on the campus on May 5-6, 1922. (See above and Prevots, p. 40).

Announcement for "Children of the Sun," May 5th and 6th, U.C. Southern Branch. Annotated with commentary by Barbara Johnson and included in a letter from her to her future husband Willard Morgan. Courtesy of Lael Morgan, granddaughter of Barbara Morgan.

The partially Japanese-themed celebration of spring was possibly influenced in some way by Gould's close friend McGehee whom she had been collaborating with on various performances since her breakup with Ted Shawn. Wardell then joined fellow UC Southern Branch faculty member Louise Sooy and Pasadena Community Playhouse director Gilmor Brown on the faculty of the Pasadena Community Playhouse's 1922 Summer Art Colony (see below). (For much more on Brown and the Pasadena Playhouse see my "WMSZ.").

Summer Art Colony for Community Drama Directors, Pasadena Community Playhouse, Summer 1922.

"Teacher of Dancing Art is Honored," L.A. Times, December 31, 1922, p. III-33.

In a later 1922 article on dance schools in Los Angeles (see above), the Norma Gould School was singled out as the one aiming "toward the highest cultural education through the use of Dalcroze Eurhythmics in the development of the dance. Referenced as the Director of Pageantry at University of California Southern Branch for the past three years and deemed a "teacher of teachers," Gould was also credited with placing Wardell on the school's faculty. By then Gould was also teaching at the University of Southern California.

April 20, 1923: Weston Daybook entry references discussion with Johan Hagemeyer over the sharpness of focus of a print of Bertha Wardell. (Earliest Daybook reference of Wardell who was at the time employed at UC Southern Campus with Pauline's sister Dorothy Gibling).

"Just now a letter from Bertha Wardell - "We are finding life interesting in the midst of a Righteous Crusade against the Wicked Dance. It has so far deprived us of the use of our studio but not of our legs so we have nothing really to complain of." Christ! Is this possible! O how sickening! My disgust for that impossible village, Los Angeles, grows daily. To think that Mexico had to abandon the fair country of California to such a fate. I ask every Mexican, "Do you wish like conditions here? If not, then fight American influence in Mexico !" But being an American I like to believe that only in Los Angeles could such a situation exist. Give me Mexico, revolutions, small-pox, poverty, anything but the plague spot of America - Los Angeles. All sensitive, self-respecting persons should leave there. Abandon the city of the uplifters." (Daybooks, Vol. I, January 18, 1924, p. 43).

It appears that Wardell and Lyndall struck out on there own around the time Weston left for Mexico indicated by articles and ads in the Los Angeles Times for their "Playhouse of the Dance" performance and studio activities. (See below for example).

Nye, Myra, "Club Notes," Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1924, p. 29.

Brochure for "The Playhouse for the Dance" sent to Mary Austin ca. April 1925. Courtesy of the Huntington Library Mary Austin Collection.

Brochure for "The Playhouse for the Dance" sent to Mary Austin ca. April 1925. Courtesy of the Huntington Library Mary Austin Collection.

Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, April 1925, front cover.

Harriet Monroe published one of Wardell's poems, "Sacrilege," in the April 1925 issue of Poetry (see above). Just a brief piece (see below), it was more symbolic of poetry's inspiration for Wardell's creative process.

Wardell, Bertha, "Sacrilege," Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, April 1925, p. 25.

Also in 1925 Wardell contributed an essay describing in great detail her creative process in Mary Austin's Everyman's Genius which reviewer Irwin Redman characterized in his negative critique as "...the work of an artist who wishes to help other workers in creation to orient and fulfill themselves." ("On Genius," Everyman's Genius by Mary Austin, Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1925. Reviewed by Irwin Edman, Columbia University, Saturday Review of Literature, January 16, 1926, p. 494). Having read some articles Austin had published on genius, Bertha contacted her to see if she would be interested in a piece on creativity in the dance. Austin replied,

"I am indeed pleased to have your letter in regard to my articles on genius. The book is just on the point of going to press, but it is possible that if you send me as complete an account as possible of the psychological processes of dance creation, I may be able to get part of it, or some mention of it into the appendix, with your name." (Mary Austin, letter to Bertha Wardell, January 20, 1925. Courtesy of the Huntington Library Mary Austin Collection).

Austin was so pleased with Wardell's essay that she included it unedtited in the appendix and strongly encouraged her to also submit it for publication in a magazine interested in the dance. Excerpts from Bertha's essay (see below) and Weston's Daybooks strongly hint that Weston read, and was influenced by, her piece prior to creating his dramatic 1927 images of her upon his return from Mexico.

"...In making a dance form, two things are necessary - a "dance idea," and the music which expresses that idea. The idea may come from something that I read - poetry, rhythmic prose, - folklore or mythology; but, it does not 'develop (that is, exist as anything but an intellectual concept) until I find music to which it is possible to think in terms of the "dance idea." For instance, when I have an "elfin" idea, I must have "elfin" music, for a Russian dance, Russian music, if the dance form evolved is to be true. ...When the dance comes, it appears as a tiny figure dancing to the music to which I am listening. The figure is on the back of my forehead. ... Sometimes I have consciously to fill in gaps when the figure is not clear, but I think it keeps on dancing just the same even though I can not see it. The figure, itself, has no sex and has no other outlines than that of a body - even in recreating national and folk dances there is no characteristic dress. The extremities are the most distinct. The face can not be seen at all. (Italics mine). ... I use poetry, etc., to keep me in the proper mood until the dance has appeared. The length of time elapsing after I have found both music and the idea until the dance formulates itself depends on the amount of time I have at my disposal to give to listening to the music. If I am interrupted in the process of creation, I am never worried, I always feel as if the dance were being well taken care of even though I am not consciously working with it. There are times though, when I am very tired and can get nothing from the music, reading, or thinking - then I play jazz and let myself go to it - just dance around. ...The only thing which seems to be essential to the creativeness in me, is love; it may be love for the dance idea or for the music. I can only express what I mean by love by saying that to me it is a state in which I give up myself utterly, or open myself to what. really is. I must have this feeling of love or the dance idea and music will not appear in dance form. I can stimulate this feeling in myself by reading something beautiful, by being with some person of whom I am very fond, or by looking at flowers. ...The dance form complete is only a skeleton. The dance pattern - that is, the direction and arrangement of the movements on the floor, and the penetration of the form with the subtle differences of moving and feeling (italics mine) which give style and character and make the dance true, are left for the dancer. ...My own process, that of translating the dance form into theatrical terms, is as follows: First, I dance over the movement rather sketchily, to get the "feel" of it, and, as I do this, I become conscious of how the movement should be executed. ...I can only describe my process by saying that, after doing the movement very easily without any thought other than to get the sequence of movements, the proper execution of them - that is, the use of head, torso, arms, and the emphasis and phrasing, follow spontaneously. (Italics mine). ...The only Oriental dances that have ever "belonged" were some native Japanese dances I once learned. [From Ramiel McGehee?]. ...After I have the sequence and the general outline of the dance form with whatever else has come spontaneously, I leave the dance for a day or two. During the time when I am not actually practicing comes the second part of the process. This consists, first of all, in enriching my associations by reading everything that may have to do with the dance - fact or fiction. If the dance is of a suitable type, I try to put the essence of it into writing. I find that the expression of an emotion or the delineation of a character will clarify itself if I can describe it in words which please me. I also use what might be called a form of meditation. ...I practice no regular spiritual exercises other than those I have mentioned, but I try to be out-of-doors as much as possible, to read poetry, highly imaginative prose, and books of travel, and never to harbor resentment. Anger, hate, or any of the destructive emotions kill creativeness." (Bertha Wardell, Playhouse of the Dance, Hollywood, California, excerpted from Everyman's Genius by Mary Austin, pp. 323-9).

Bertha shortly thereafter sent Austin a companion essay, "Some Social Aspects of the Dance," which also made quite an impression as indicated in Austin's below response. She further invited Bertha to visit her in Santa Fe to study American Indian dance.

Mary Austin, letter to Bertha Wardell, March 20, 1925. Courtesy of the Huntington Library Mary Austin Collection.

Austin and Wardell continued corresponding and they finally met when Mary came to Los Angeles for a May 30th lecture at the Women's University Club. Austin prevailed upon Wardell to take her shopping for a dress for the occasion. (Mary Austin, letter to Bertha Wardell, May 24, 1925. Courtesy of the Huntington Library Mary Austin Collection).

Wardell and a close group of U. C. Southern Branch Art and Physical Education Department faculty friends including Annita Delano, Barbara Morgan and Irene Palmer, spent most of August 1925 at Morro Bay painting and dancing among the dunes with the backdrop of Morro Rock. Delano had discovered the area the previous summer on her way home to Porterville to visit her family. Most of the above and below photos of Bertha and friends were likely taken by Morgan presaging her later career as a photographer and most notably her dance photography featuring her early 1920s acquaintance Martha Graham.

Irene Palmer, Annita Delano and Barbara Morgan at Morro Bay, August 1925.. Photographer unknown for certain but likely Bertha Wardell. Courtesy of Lael Morgan.

Wardell and a close group of U. C. Southern Branch Art and Physical Education Department faculty friends including Annita Delano, Barbara Morgan and Irene Palmer, spent most of August 1925 at Morro Bay painting and dancing among the dunes with the backdrop of Morro Rock. Delano had discovered the area the previous summer on her way home to Porterville to visit her family. Most of the above and below photos of Bertha and friends were likely taken by Morgan presaging her later career as a photographer and most notably her dance photography featuring her early 1920s acquaintance Martha Graham.

Bertha Wardell at Morro Bay, August 1925. Photographer unknown for certain but likely Barbara Morgan. Courtesy of Lael Morgan.

Bertha Wardell at Morro Bay, August 1925. Photographer unknown for certain but likely Barbara Morgan. Courtesy of Lael Morgan.

Wardell and fellow UCLA instructor, artist and soon-to-be Schindler-Weston circle habitue Barbara Morgan, attended weekly 1-1/2 hour sessions conducted by Isadora Duncan during 1926-7. (Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, p. 350). Morgan's mutual interest in body movement inspired her later passion for dance photography made famous by her work with Martha Graham in New York beginning in 1935. (For much more on Barbara and Willard Morgan see my LAMod).

Lyndall, Dorothy S., Who's Who in Music and Dance in Southern California, Hollywood: Bureau of Musical Research, 1933, p. 217.

Dorothy Lyndall (see above) and Wardell associated with Mikhail Mordkin, former director of the Bolshoi Ballet, during his early 1927 Los Angeles sojourn, coordinating and assisting in his "master" classes per the below ad. Also note the competing ads of the Denishawn and Norma Gould Schools. It wasn't mush after this that they apparently decided to go their separate ways.

Ballet master Theodore Kosloff teaching the Paramount Studio chorus girls, ca. 1922. Photographer unknown. From arts-meme.

About the same time Wardell published an article in The Dance devoted to the a discussion of the ballet at the Philharmonic Auditorium during the 1927 season. (Author's note: See below example period cover of The Dance to which Wardell frequently contributed). The article included an interview with Theodore Kosloff in which he talks about his production of 'Scheherazade' at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium and 'The Volga Boatman' at the Circle Theatre. Wardell wrote,

"Theodore Kosloff was rehearsing Scheherazade. The huge bare room where the rehearsal was being carried on hummed with vitality; the life of the fiery ballet, its story of the Eastern soul coming to itself again; the disturbing music of Rimsky Korsakoff being pounded on the piano; the desperate faces of the dancers as they dashed about, bodies streaked with dirt from squirming on the floor, faces and bodies shining with sweat; Kosloff, his square body .. with feet apart planted on the sidelines, every wave of movement running through him, his baton stumping on the floor. ... Mr. Kosloff told me as he rested, "Last night I stayed up until midnight making the formation of th is ballet with colored papers. This morning I got up at half-past four because we rehearse at quarter-to-seven. I quit my classes here in the studio, I leave my work in the moving pictures with Mr. Cecil De Mille, for whom I am technical art director, to do this ballet." (Wardell, Bertha, "The Scheherazade in Hollywood," The Dance, January 1927, pp. 31, 64 and Prevots, pp. 125-6).

Ruth St. Denis cover, The Dance, April 1929. From Magazine Art.

Shortly after Edward and Brett's return from Mexico, their work was exhibited at UCLA, through the largess of Wardell's UC Southern Branch art teacher colleagues, Annita Delano and Barbara Morgan, who were both Weston-Schindler circle regulars. (February 13, 1927, Daybooks, Vol. II, p. 5. For more on Delano and Morgan see my LAMod). Having soon seen the exhibit Bertha wrote Edward,

"My dear Edward Weston: - Your photographs affected me a great deal. Even to think of them gives me a feeling of reality, of things falling - and fallen - into their proper relations. Someone asked me which studies I had liked. For the life of me I couldn't remember - the effect seemed to be a sum-total reaction. Except for the studies of bodies! I shall own some of these one day. I must. It is not often that anything says "dancing" to me as these do. The body - so present - so soft and warm to touch - the source of so many beauties and delights - yet so mysterious. Barbara Morgan says you are sometimes in need of a model. If I could help I would be happy to lend myself. Tuesday afternoons I have free. Sometimes, Fridays too. Cordially, Bertha Wardell." (Edward Weston: His Life by Ben Maddow, Aperture, 2000, p. 151. For Weston's acknowledgement of this letter see February 26, 1927, DaybooksII, p. 6).

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

"... - a kneeling figure cut at the shoulder (see above), but kneeling does not mean it is passive, - it is dancing quite as intensely as if she were on her toes! (See below). I am in love with this nude - - -." (Daybooks Vol. II, May 14, 1927, p. 27).

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Weston's deft capturing of the Wardell's musculature is immediately brought to mind in the description of one of her partner Dorothy Lyndall's later students Janet Collins."I remember how [Lyndall] had us take some dancer's working anatomy classes from a learned lady acquaintance of hers called Bertha Wardell, who taught us among many things about the correct ballet turnout, which origin is in the hip joints, and how to use the two sets of muscles we dancers must use in this process - the adductor and abductor muscles of the thighs. Muscular activity becomes real to a dancer when you actually feel and experience those muscles at work! It is a wonderful feeling of muscular control over your own body - and you know it is right because it alone produces the desired results." (Night's Dancer: The Life of Janet Collins, by Yael Tamar Lewin, Weslayen University Press, pp. 62-3).

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Knees, Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. From Edward Weston: Photography and Modernism by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Karen Quin and Leslie Furth, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1999, Plate 31. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

"B. sat to me again: six negatives exposed, all of some value, three outstanding, but two of the latter slightly moved. However, the one technically good is the one best seen. As she sat with legs bent under, I saw the repeated curve of thigh and calf, - the shin bone, knee and thigh lines forming shapes not unlike great sea shells, - the calf curved across the upper leg, the shell's opening. I made this, cutting at waist and above ankle (see above). After the sitting I fell asleep, sitting bolt upright, supposedly showing Bertha some drawings, - I was that worn out. These simplified forms I search for in the nude body are not easy to find, nor record when I do find them. There is that element of chance in the body assuming an important movement: then there is the difficulty in focusing close up with a sixteen inch lens: and finally the possibility of movement in an exposure of from 20 sec. to 2 min., - even the breathing will spoil a line. If I had a workroom such as the one in San Francisco with a great overhead and side light equal to out of doors, I would use my Graflex: for there I made 1/10 s. exposures with f/11, - in this way I recorded Neil's body. Perhaps the next nudes I will try by using the Graflex on tripod: the 8 inch Zeiss will be easier to focus, exposures will be shorter, films will be cheaper! My after exhaustion is partly due to eyestrain and nerve strain. I do not weary so when doing still-life and can take my own sweet time. B. has a sensitive body and responsive mind. I would keep on working with her." (March 24, 1927, DBII, p. 10).

Bertha wrote Weston the next day,

"My dear Edward Weston: - You and your work have been very strongly in my mind since yesterday. You yourself seemed possessed for an instant not only of a physical, but of a psychic fatigue. I wished that you had not worked so long. It disturbed me; I think, especially because of the exceeding delicacy and vitality of your work which is dependent to a certain extent, at least, on the vitality of your body. What you do awakes in me so strong a response that. I must in all joy tell you. Perhaps it will seem out of proportion to you, in whom it has grown gradually, but, on the other hand, perhaps only someone from without can sense what you do in its true proportions. Your photographs are as definite an experience to the spirit as a whiplash to the body. It is as if they said, "Look - here is something you have been waiting for something you have not found in painting or even in sculptures. Something which has been before only in the thought of dancing." It has so enlivened my own feeling about dancing that something of that may be born yet - and not dead. I beg of you - do not come to the dancing Sunday. This envelope is very empty of a card. Some day, if you will let me -I would like to dance for you. It was very happy and restful posing for you. If there is anything you want to do again however - you must feel free to send me away if you find yourself too weary. There is the danger that this will strike you in the wrong mood, that it may seem sentimental and loquacious when words about your work should in all appropriateness have finesse and reserve. All of which I risk gladly, hoping that the weariness was not unavailing - that the afternoon may have brought forth something which you can enjoy having made. BBW." (Edward Weston: His Life by Ben Maddow, Aperture, 2000, p. 152-3).

References to Bertha frequently appeared in Weston's Daybooks over the next few months, for example:

March 25. ... Came a letter from B. which well indicates her response: ... (see letter above). This letter also indicates why I would work more with her.

March 30. Henrietta Shore asked me to sit to her. I am sure no one else could tempt me to so spend time, but certainly I respond to this real opportunity. The shells I photographed were so marvelous one could not do other than something of interest. What I did may be only a beginning - but I like one negative especially. I took a proof of the legs recently done of Bertha, which Miss Shore was enthusiastic over.

April 1. Nudes of [B?] again. Made two negatives, - variation on one conception. I am stimulated to work with the nude body, because of the infinite combinations of lines which are presented with every move. And now after seeing the shells of Henrietta Shore, a new field has been presented.

April 2. ... The last nude of B., - good.

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

April 13. Tuesdays are now definitely B. day. She enjoys working with me, and I respond to her. Her beauty in movement is an exquisite sight. Dancing should be always in the nude. I made 12 neg's,- for the first time using the Graflex: arrested motion however, for the exposures were three seconds. But these negatives will be different in feeling, for the ease of manipulation of a Graflex allows more spontaneous results.

April 15. Printed some of my new negatives which I want to show Henrietta Shore. I go to sit for my portrait today. Tina writes she is "crazy about the two nudes"- the backs of Cristal. (See later below for example). And now I am almost "crazy" over several of the recent negatives of B. I shall work with the Graflex for awhile.

April 16. Not so early as usual: Henrietta Shore and I talked till late. The portrait started. She asked me not to look at it until much more work had been done. ... Of my new work, she liked well the legs of Bertha, - the forms Peter thought were great shells...

Bertha Wardell, 1927. Edward Weston photograph. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

April 20: ... B. came for her Tuesday session: when she went our association had assumed a new aspect! I had before, vague questionings as to whether her coming was an entirely impersonal interest in my work, knowing definitely how strong that response was, but though she has been with me these many afternoons, - danced before me naked, I have never felt the slightest physical excitement. I admired her mind, I thought her body, especially in movement, superb, - but nothing more. Even yesterday, it was not until she was dressed and we sat together exchanging thoughts, that I became fully aware of her real feeling for me. Our hands clasped, - our lips met, - ... then I had to go before a fulfillment. As an artist, B. is more definite than anyone I have met since Mexico, excepting Henrietta Shore. Our association should be constructive to both. My life may become complicated with three lady loves to consider, and I don't want that: quite the contrary, I crave simplicity.

April 23: ... I showed Henrietta the last nude of Bertha: legs and feet in action. I had a direct plain-spoken reproof. "I wish you would not do so many nudes, - you are getting used to them, the subject no longer amazes you, - most of these are just nudes." (I knew she did not mean they were just naked, but that I had lost my "amazement.")

April 24: What have I, that bring these many woman to offer themselves to me? I do not go out of my way seeking them, - I am not a stalwart virile male, exuding sex, nor am I the romantic, mooning poet type some love, nor the dashing Don Juan bent on conquest. Now it is B[ertha].

April 28: ... And then the dancing nudes of B. I feel that I have a number of exceedingly well seen negatives, - several which I am sure will live among my best. B. left me a record of one of Chopin's Preludes played by Casals. Starting a tender, plaintive melody, it suddenly breaks, quite without warning into thundering depths, and then in a flash rises to electrifying heights, which makes my scalp tingle.

April 29: The last dancing nudes of B. were 24 neg's: 20 have interest, - 14 can be considered for finishing - 7 I do not hesitate over, - they will be added to my collection, and hold there with my very best. This is seeing well! ...

April 30: ...Now it is Bertha in whom I have kindled a perfect flame! She wrote to me "danse motives," written day by day in a fervor of desire... B. came with undiminished enthusiasm, but I did not work so well: I was tired and confused: it was a hectic day! ... B. had not gone when K. arrived. I wonder if K. comes out of my curiosity over B.? It seems more than coincidence that she has called several times on Tues. I had to be very diplomatic. K. is a bit of an exhibitionist in love making. Well B. had no sooner gone than E. came again! I call this day a mad one, with three loves to respond to! Bertha is still.....I have been fair to her, even when profoundly excited. She would gasp, "No, Edward, I can give you no more," and I would stop.... (Maddow, p. 155).